eBook - ePub

Developmental Disorders of Language Learning and Cognition

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developmental Disorders of Language Learning and Cognition

About this book

This important new text is a comprehensive survey of current thinking and research on a wide range of developmental disorders.

- Highlights key research on normal and typical development

- Includes clinical case studies and diagrams to illustrate key concepts

- A reader-friendly writing style

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Developmental Disorders of Language Learning and Cognition by Charles Hulme,Margaret J. Snowling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Understanding Developmental Cognitive Disorders

John, Peter, and Ann are three 7-year-old children. John’s parents and teachers have concerns about his progress in learning to read. John is generally bright and understands concepts well. Formal testing showed that he had a high IQ (120) with somewhat higher scores on the performance than the verbal scales of the test. John could only read a few simple words on a single word-reading test – a level of performance equivalent to a typical 5½-year-old child. John does not know the names or sounds of several letters of the alphabet. Verbally John is a good communicator, though he does show occasional word-finding problems and occasionally mispronounces long words. John is a child with dyslexia.

Peter is also a bright little boy (IQ 110, but with markedly lower scores on the performance than the verbal subtests). He has made a very good start with learning to read, and on the same test given to Peter he read as many words correctly as an average 8-year-old child. Peter has severe problems with games and sport at school, particularly with ball games. He is notably ill-coordinated and frequently drops and spills things. He has very serious difficulties with drawing and copying, and his handwriting is poorly formed and difficult to read. Peter has developmental coordination disorder.

Ann is a socially withdrawn child. She avoids interacting with other children in school whenever she can. She is sometimes observed rocking repetitively and staring out of the classroom window. Ann’s communication skills are very poor, and she appears to have quite marked difficulties understanding what is said to her, particularly if what is said is at all abstract. When an attempt was made to give Ann a formal IQ test, testing was discontinued because she refused to cooperate. The few items she did complete suggested she would obtain a very low IQ score. Ann is fascinated by cars and will spend many hours cutting out pictures of them to add to her collection. Ann is a child with autism.

These three cases of 7-year-old children illustrate some of the varied cognitive problems that can be observed in children. In this book we will attempt to provide a broad survey of the major forms of cognitive disorder found in children, and lay out a theoretical framework for how these disorders can best be understood. Understanding these disorders, in turn, holds prospects for how best to treat them. Our approach to these disorders is from a developmental perspective, by which we mean that a satisfactory understanding of these disorders needs to be informed by knowledge of how these skills typically develop. Most of the explanations we consider in the book will focus on the cognitive level: a functional level dealing with how the brain typically learns and performs the skills in question. Wherever possible, however, we will relate these cognitive explanations to what is known about the biological (genetic and neural) mechanisms involved in development. The interplay between genetic, neural, and cognitive explanations for behavioral development is currently an area of intense activity and excitement.

Some Terminology for Classifying Cognitive Disorders

In this book we will consider a wide range of developmental disorders that affect language, learning, and cognition. The disorders considered include those affecting language, reading, arithmetic, motor skills, attention, and social interaction (autism spectrum disorders). There are a number of features that are shared by the disorders we will discuss: they all occur quite commonly and have serious consequences for education, and thereafter for well-being in adulthood. There is also good evidence that all these disorders reflect the effects of genetic and environmental influences on the developing brain and mind.

To begin with it is important to distinguish between specific (or restricted) difficulties and general difficulties. Specific difficulties involve disorders where there is a deficit in just one or a small number of skills, with typical functioning in other areas. General difficulties involve impairments in most, if not all, cognitive functions. Terminology in this field differs between the UK and the USA; we will consider both here, but we will use primarily British terminology in later sections of the book.

In the UK a selective difficulty in acquiring a skill is referred to as a “specific learning difficulty.” The term learning difficulty makes it clear that skills must be learned; specific means that the difficulty occurs in a restricted domain. Dyslexia is one of the best known and best understood examples of a specific learning difficulty. Children with dyslexia have specific difficulties in learning to read and to spell, but they have no particular difficulty in understanding concepts and may have talents in many other areas such as science, sport, and art. In the USA (following DSM-IV, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association) such specific difficulties are called learning disorders.

Specific learning difficulties can be contrasted with general learning difficulties (or, in US terminology, mental retardation). General learning difficulties involve difficulties in acquiring a wide range of skills. People with the chromosomal abnormality of Down syndrome, for example, usually have general learning difficulties and typically have problems in mastering all academic skills and with understanding in most domains. In this book we will focus upon specific learning difficulties.

In practice, the distinction between specific and general learning difficulties is often based on the results of a standardized IQ test. IQ tests (or measures of general intelligence) are highly predictive of variations in attainment in all manner of settings. The average IQ for the population is 100 (with a standard deviation of 15 points). In the UK people with IQ scores between 50 and 70 are referred to as having moderate learning difficulties, and people with IQ scores below 50 are said to have severe learning difficulties. US terminology distinguishes between mild (50–70), moderate (40–50), severe (25–40), and profound (IQ below 20) mental retardation. Often the diagnosis of a specific learning difficulty is made only in cases where the child achieves an IQ score in the average range (perhaps an IQ of 85 or above).

Operationally the distinction between specific and general learning difficulties is therefore quite clear: children with specific learning difficulties typically have average or near to average IQ scores, while children with general learning difficulties have IQ scores below 70. Conceptually, however, the distinction is probably a bit more slippery. It is important to appreciate that there is a continuum running from the highly restricted deficits found in some children (e.g., a child with a severe but isolated problem with arithmetic), to more general difficulties (e.g., a child with severe language difficulties who has difficulties both with understanding speech and expressing himself in speech), to very general difficulties (a child with an IQ of 40, who is likely to have problems in reading and spelling, as well as spoken language, together with a range of other problems including problems of perception, motor control, and general conceptual understanding). One aim of this book is to convey an appreciation of how studies of children with different types of learning difficulties have contributed to an understanding of how a range of different brain systems are involved in learning. The range of learning difficulties that occurs ultimately helps us to understand how the developing mind is organized and how the skills that are impaired in some children are typically acquired.

Levels of Explanation in Studies of Developmental Cognitive Disorders

What form of explanation can we hope to achieve for developmental cognitive disorders? It is important to distinguish between the different levels of explanation that are possible. Morton and Frith (1995) have laid out very clearly the logic and importance of distinguishing the different levels of explanation that are needed for understanding developmental disorders. They show how it is essential to consider three major levels of explanation: biological, cognitive, and behavioral. At each of these levels underlying processes (in the child) interact with a range of environmental influences to determine the observed outcome.

We can illustrate the role of different levels of explanation with reference to conduct disorder, a disorder of socio-emotional development that we will not deal with further in this book. Conduct disorder is a disorder where there have been advances in understanding at several different levels recently (Viding & Frith, 2006) and it is

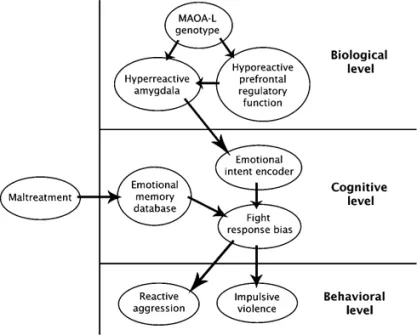

therefore a good example to illustrate the different levels of explanation involved in the study of developmental disorders. Conduct disorder is defined in DSM-IV as persistent antisocial behavior that deviates from age-appropriate social norms and violates the basic rights of others (American Psychiatric Association, 1994); alternative terms sometimes used for this disorder include antisocial behavior and conduct problems. A model for one aspect of conduct disorder – reactive aggression – proposed by Viding and Frith (2006) is shown in Figure 1.1 below.

This model represents processes operating at the biological, cognitive, and behavioral levels of explanation. It appears that at the biological level specific differences in genes that regulate the action of the neurotransmitter serotonin are important in giving rise to a predisposition to commit acts of violence. More specifically, different variants (alleles) of a gene coding for monoamine oxidase inhibitor A (MAOA) have been identified, with either high (MAOA-H) or low activity (MAOA-L). Research has suggested that having the MAOA-L gene may predispose an individual to display violent behavior but only if they experience maltreatment in childhood (Caspi et al., 2002). (This is a very important finding since it provides an example of gene–environment interaction; neither having the gene nor being maltreated alone may be sufficient but both factors together give a greatly increased risk of developing conduct disorder.) These genetic and environmental risk factors in turn appear to operate on the development of brain systems concerned with the regulation of emotion. In particular it is thought that the MAOA-L gene may be associated with the development of hyperresponsivity of the amygdala during emotional arousal coupled with diminished responsivity of areas of the prefrontal cortex that normally play a role in regulating such emotional responses. This pattern of brain dysfunction might be seen as providing the biological basis for reacting excessively emotionally and violently when provoked by certain environmental conditions (in everyday terminology, losing control or “losing it” when provoked).

Figure 1.1 A causal model of the potential gene–brain–cognition–behavior pathways from MAOA-L to reactive aggression. (Adapted from Viding, E. & Frith, U. Genes for violence lurk in the brain. Commentary. Proceedings for the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 6085–6086. Copyright (2006) National Academy of Sciences, USA.)

Viding and Frith suggest that these brain differences express themselves at the cognitive level via a mechanism called an emotional intent encoder, which in turn is associated with a bias to fight. Interestingly, in this model, Viding and Frith explicitly propose that the interactive effects of childhood maltreatment operate at a cognitive level by leading to the creation of many emotionally charged memory representations. This is an interesting and testable hypothesis, but of course such effects may also operate at a biological level as well as, or instead of, at the cognitive level.

The final level in the model is the behavioral level, where the fight response bias mechanism may lead to reactive aggression (fighting when provoked) as well as impulsive violence.

A complete explanation of any disorder will involve at least three levels of description. For one aspect of conduct disorder – reactive aggression – genes appear to contribute powerfully to the risk of developing the disorder in interaction with specific environmental experiences (maltreatment) in childhood. It appears that these genetic effects in turn affect the development of brain circuits concerned with the experience and regulation of emotion, perhaps particularly anger, which, in interaction with memories of previous experiences associated with violence, may lead to a bias toward fighting (rather than running away or being afraid). At a behavioral level, this bias toward a fight response may lead to the observed profile of responding violently when provoked and occasionally committing unprovoked, impulsive acts of violence.

Morton and Frith (1995; Morton 2004) argue that it is useful to make explicit diagrams of these sorts of theoretical explanations, using an approach they term causal modeling. The Viding and Frith diagram (Figure 1.1) is an example. It is important to note that the arrows in such a diagram represent hypothetical causal links. According to this model, a genetic difference causes a brain difference (abnormality), which in turn causes cognitive (emotional) deficits, which in turn cause the observed behavioral patterns (a propensity to violence). Note that within this framework environmental effects can be thought of as operating at each level. So, for example, a virus or early brain injury might also lead to the brain abnormality underlying the emotion control problem, and the effects of positive experiences (a nurturant nonaggressive parental style) might prevent the development of the emotion regulation deficits. Some forms of treatment (teaching anger management strategies) might also have effects on the behavioral level (inhibiting violent outbursts) without having a direct effect on the cognitive level (the person may still feel angry and feel the urge to lash out, but develop ways of controlling such feelings).

It is important to emphasize that all three levels of description are useful, and each helps us to understand the disorder. While links can and should be made between these different levels of explanation, we cannot reduce or replace one level of explanation with a lower level. The cognitive level of explanation (emotion encoding) cannot be replaced by a neural explanation (problems with the amygdala). We would note here that we have followed Morton and Frith’s terminology by referring to the level between the brain and behavior as “cognitive.” This might seem too narrow a term because cognition essentially refers to thought processes. We will stick with this term for the moment, though in some of the disorders we consider later (as well as in the case of conduct disorder) this terminology might usefully be broadened to consider other forms of mental processes, particularly emotional and motivational processes, that probably cannot simply be reduced to cognition. The point, however, is that we need a level of “mind” or “mental process” as an intervening level of explanation between brain and behavior. We would also argue, in light of recent advances in our understanding of developmental disorders, that the causal model presented in Figure 1.1 is too unidirectional to capture the truly interactive nature of development. It is also necessary to postulate causal arrows running “backwards” from lower levels to upper levels. This at first seems counterintuitive, but some examples help to explain why it is necessary.

Can changes at the behavioral level alter things at the cognitive level? Almost certainly yes. If we take the example of teaching anger management strategies mentioned above, it may be that such training will work by modifying the cognitive mechanisms associated with emotional encoding; seeing a person grin could be interpreted simply as showing that they were happy rather than indicating they are intending to insult you. Do such changes at the cognitive level depend upon changes in underlying brain mechanisms? Again it would seem likely that they do. Connections between nerve cells may be modified by experience and this in turn will result in lasting structural and functional changes in the circuits responsible for encoding and regulating emotion.

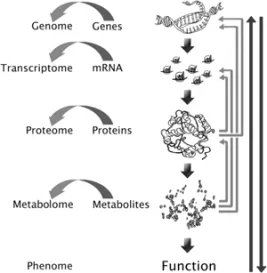

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, we can consider whether changes at the behavioral and cognitive levels can affect things at the genetic level. Most people would probably doubt this proposition. Our genetic makeup is fixed (we inherit our DNA at conception and experiences are not going to alter it), this is true, but there is evidence that experiences can alter the way genes are expressed. Genes (genes are sequences of base pairs in DNA) do not regulate development directly. Rather, genes control the production of messenger RNA (mRNA), and mRNA in turn controls the production of proteins in cells. Furthermore, mRNA molecules degrade quickly so that if more of a protein is needed the cells concerned have to keep manufacturing more mRNA. Changes in the rate at which a gene produces mRNA will therefore result in changes in the rate at which the protein coded is produced in a cell. The levels of regulation in cells, as currently conceptualized by molecular biologists, are shown in Figure 1.2. Once again, in this diagram there are different levels of explanation: the genome (the genes that consist of sequences of base pairs in DNA), the transcriptome (the mRNA produced under the control of the base sequences in the DNA), the proteome (the proteins produced under the control of mRNA), the metabolome (the products of proteins and other chemicals created by metabolism in the cell), and the phenome (the functioning of the cell within its environment in the body).

Figure 1.2 Diagram showing the complexities of genetic mechanisms. There are potentially numerous interactions at each level, as well as bidirectional influences between levels. All these parameters may differ between different developmental stages or in different tissues of the body. (With kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media. Metabolomics, Metabolomics – the way forward, 1, 2005, p. 2, Goodacre, R., fig.a.)

As shown in Figure 1.2, there are bidirectional arrows connecting these different levels (not a one-way arrow flowing from DNA to Function). One of the ways in which experiences may affect the expression of the genome is through the operation of control genes. Such control genes exist to control the operation of other genes by switching these other genes on or off (i.e., making genes either produce or stop producing mRNA). It now appears that such control genes may cause other genes to be switched off in response to changes in the internal and external environment. One remarkable example of such effects is shown by the observation that tweaking a rat’s whiskers may cause changes in gene expression in the animal’s sensory cortex (Mack & Mack, 1992). Similarly, when a songbird hears their species’ song this experience may operate to change the expression of genes in the brain (Mello, Vicario, & Clayton, 1992). Thus, we need to accept that environmental effects may result in changes in the way genes are expressed. Such changes in gene expression may in turn result in long-lasting changes in the neural structures whose development is partly under genetic control (see Plomin, DeFries, McClearn, & Rutter, 1997, for more details).

In line with these findings from animals it has been shown that in human monozygotic (identical) twin pairs there are measurable differences in patterns of gene expression (differences in the genes that are active or being expressed). Furthermore, these differences in gene expression increase with age and tend to be greater for twin pairs who have lived apart for longer and who have experienced greater differences in lifestyle and health (Fraga et al., 2005). These effects clearly suggest that differences in experience produce different patterns of gene expression in people and that such differences may be responsible for differences in health and brain development that may have effects on behavior.

Summary

We hope that our discussion makes clear that the environment affects how our genetic makeup is expressed. The patterns of gene expression in cells will differ in different tissues and at different stages of development. The tissues most relevant for explaining differences in behavior are those in the nervous and endocrine (hormonal) systems. The most important point for the present argument is to appreciate that experiences may affect the processes involved in gene expression. Viewed in this way, the genome is not fixed in the way it operates throughout development. Rather, the genome receives signals from the environment that can turn genes on or off in different tissues of the body (including the brain). This means that differences in our experiences may well affect how genes that play a role in controlling brain development are expressed.

For most of this book we will be concentrating on explanations for developmental disorders that seek to relate observed impairments at the behavioral level to deficits at the cognitive level. We believe that such cognitive explanations are important and valid in their own right. A cognitive explanation of a disorder is essentially a functional explanation, couched in terms of how a particular skill is learned and performed, and in what ways this typical functioning is disturbed. Such an explanation is satisfying in its own right, and also has practical importance, in that it relates closely (though always indirectly) to how we can best assess and treat a disorder. This is not to say that biological levels of explanation are not also important. We will, where appropriate, cite evidence about the biological mechanisms underlying the cognitive level of explanation, particularly where such biological evidence places constraints on the types of cognitive explanation that are most viable. As has already been made clear from the brief account of research on conduct disorder above, there are two levels of biological mechanism that may be particularly relevant to the study of developmental cognitive disorders: genetic and brain mechanisms. We will consider very briefly the way in which these mechanisms are studied.

Genetic Mechanisms

There are two levels at which the genetic basis of a disorder can be studied. Population genetic studies examine the patterns of inheritance of a disorder across individuals. Molecular genetic studies go beyond this and identify certain genes (DNA sequences) or gene markers that are associated with the development of a disorder. Both of these levels of analysis have been applied in the case of conduct disorder.

Population genetic studies relate variations in genetic association to degrees of similarity in the phenotype (observed characteristics). Basically, if a characteristic is inherited, people who ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title page

- Copyright

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- List of Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Understanding Developmental Cognitive Disorders

- 2 Reading Disorders I: Developmental Dyslexia

- 3 Reading Disorders II: Reading Comprehension Impairment

- 4 Specific Language Impairment

- 5 Mathematics Disorder

- 6 Developmental Coordination Disorder

- 7 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- 8 Autism

- 9 Understanding Developmental Cognitive Disorders: Progress and Prospects

- Glossary

- References

- Subject Index

- Author Index