![]()

Chapter One

The Decision to Trust

Trust is central to human existence. Like all social animals, human beings have an instinctive need to cooperate and rely on each other in order to satisfy their most basic emotional, psychological, and material needs. Without trust, we are not only less happy as individuals but also less productive in groups. Research has linked the virtues and benefits of trust to economic prosperity, societal stability, and even human survival.1 The powerful effect of trust is that it enables cooperative behavior without costly and cumbersome monitoring and contracting. In short, trust is a form of social capital that enhances performance between individuals, within and among groups, and in larger collectives (for example, organizations, institutions, and nations).

Yet even though the decision to trust is so important, most of us can provide only rudimentary explanations of why we choose to trust certain people, groups, and institutions and not others. Trust, like love and happiness, is difficult for people to explain in clear, rational terms. This often makes us very bad trustors (a person deciding to trust or distrust). It also can create problems for us in life. We extend trust with only a vague sense of our reasons for trusting, and we unknowingly create an incentive and a market for untrustworthy opportunists who rely on a steady supply of naïve trustors. In not understanding trust, we may also fail to grasp why someone might be wary of giving us his or her trust. Worst of all, we may sometimes act unintentionally in ways that erode others' trust in us.

We make different kinds of trust errors. Sometimes we choose to trust people, groups, and organizations that do not warrant that trust. Other times, we choose not to trust even though trust is warranted, and we miss out on opportunities as a result. For example, studies have shown that many people underestimate the trustworthiness of others and that this induces these others not only to be less trusting but also less generous.2 Emotions and gut feelings can often outweigh data. There are even people who err by adopting a default decision of distrust in order to protect themselves from the pain of betrayal and disappointment. They might be happier on the whole if they chose to trust more often and to endure some betrayal as a necessary price in the pursuit of happiness.3

By trusting, you make yourself vulnerable to loss. Questions of whom to trust, how far to extend that trust, and how to avoid betrayal of trust extend into all our important relationships, including those with our employers, the government, and other large institutions. The choices we make in answering these questions can have profound effects on the course of our lives, which is why so many classics of world literature are suffused with themes of trust and betrayal. From The Odyssey to Hamlet, all the way through to such modern classics as The Brothers Karamazov and Catcher in the Rye, the question of how much one can trust—whether it be a loved one, authority figure, or government—has plagued literature's heroes.

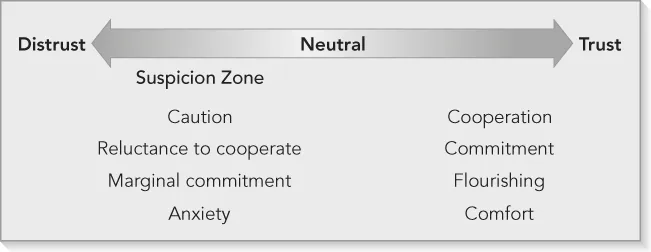

Distrust can be healthy and advisable, but when present in the extreme and in the wrong situations, it corrodes the cooperative instinct. It turns collaborative exchange into a slow and anxious mess of protective maneuvers.4 We know from research that our beliefs and judgments about trustworthiness affect our intentions and behaviors toward others in fundamental ways. Consider the consequences that research shows are related to high or low trust (illustrated in Figure 1.1).5

Without trust, people are more anxious and less happy; leaders without trust have slower and more cautious followers; organizations without trust struggle to be productive; governments without trust lose essential civic cooperation; and societies without trust deteriorate. In short, if we cannot generate adequate and reasonable perceptions of trust, through agents acting in a trustworthy manner, our lives will be more problematic and less prosperous.

A Deeper Look into the Decision to Trust

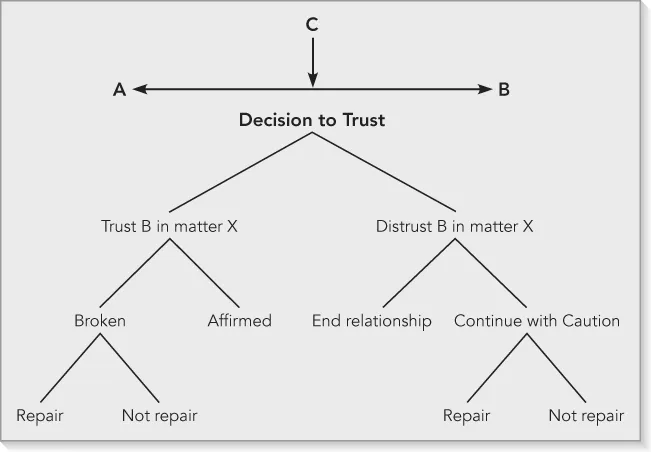

Researchers have studied trust as a decision process and identified the inputs we typically consider in making this decision.6 We will consider the inputs to the trust decision in the next chapter, but for now we will concentrate on the trust decision process. As Figure 1.2 shows, every decision to trust is made within a situational context. You decide to trust person B in matter X, and this will be influenced by the situational factors represented by C. For example, you may trust your spouse with home repair (matter X), but not with your home finances. You would never trust a total stranger with your expensive digital camera—unless the stranger is standing a few feet away and you've asked him to snap a vacation picture of you and your companion at the Grand Canyon (situation C).

The decision to trust presents itself when both uncertainty and vulnerability are at hand. When things are totally predictable, the question of trust does not arise. But when you hand that stranger your camera at the Grand Canyon, you can't be absolutely certain that he won't either drop it or run off with it. Your decision to trust—your confident reliance that he will return the camera to you unharmed—is partly based on your choice to accept some uncertainty in the situation. But even in an uncertain situation, if you don't feel any true vulnerability, then trust is really not an issue. If you were to lend a cheap pen to that same stranger at the Grand Canyon and you have three others in your pocket, you haven't made a substantive decision to trust because whether or not you get your pen back is not of any real concern to you. Trust is most helpful when we are faced with risk and uncertainty and the possibility of injury. In important matters, when we decide to distrust, a relationship usually ends or continues under duress unless it can be repaired.

Consider the following scenarios that involve the decision to trust:

- You and your spouse are about to purchase a house. You are torn about how much to rely on your real estate agent, who has told you that the price is fair, the schools are great, and the neighbors are wonderful. It is the biggest decision you and your spouse have made since marrying.

- Your company has just announced that it is merging with another firm. Your boss tells you that your position is safe. How much of your energy do you put into making the merger work versus actively seeking other job opportunities?

- You have just taken over as CEO of a firm, and you realize that your direct reports and the functions they lead do not trust each other or share information, and your customers and profits are suffering. You are leading a collection of groups that are not integrated and not performing, and you know that you will lose your job if you cannot repair this sinking ship.

You may ruminate more in some scenarios, and you may have more options in certain cases, but in each situation you will come to some judgment about how comfortable you are relying on a trustee (a person, group, organization, or institution to whom something is entrusted). Research shows that this trust judgment is related to your disposition to trust and your perceptions of the trustworthiness of the trustee.7 You assess attributes of trustworthiness and the situation in making a trust judgment. The judgment you make influences your behavior toward the trustee—for example, whether you share information or the degree to which you take protective measures with this trustee in this situation.

Interdependence is an inescapable fact of life, and we cannot predict the future with certainty, but we can understand the set of factors that go into making a good trust decision. Trust errors often occur when we fail to consider one or more of these key trust factors. If you familiarize yourself with the mental calculations involved in the decision to trust, if you understand the underlying causes of trust, it stands to reason that you will make wiser, better-informed decisions. Furthermore, if you are able to predict the conditions under which people will trust, then you should be able to manage trust and earn the trust of others.

The State of Trust over Time

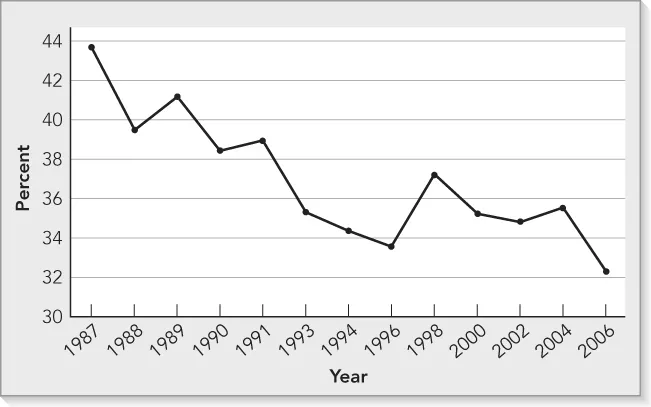

One way to understand the trust decision is to examine it over time. Fortunately, social scientists have been measuring the degree to which we trust or distrust for a long time. The findings show a disturbing trend of declining trust in major social institutions, including government, in nearly all advanced industrialized democracies.8 In the United States, trust has been in gradual decline since the early 1970s, following a dramatic drop in the 1960s. In the 1960s, surveys indicated that about 59 percent of people agreed with the statement “Most people can be trusted.” Figure 1.3 presents this generalized trust data from the General Social Survey beginning in 1987, when they began to be collected regularly. The data represent face-to-face in-person interviews in the United States with a randomly selected sample of adults.9 The survey results indicate a steady decline, with the most recent scores showing that only about one-third of respondents agree that most people can be trusted.

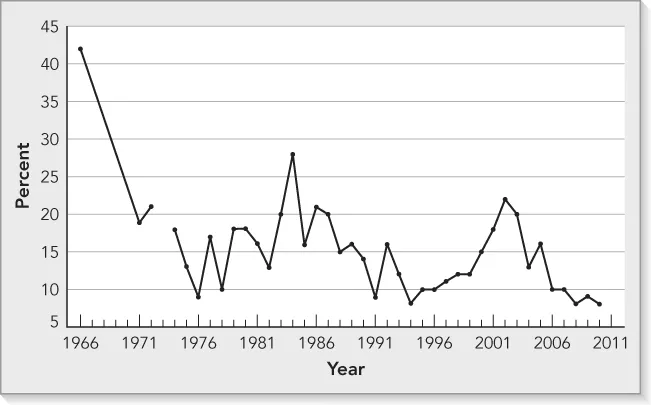

Because trust is often defined as “confident reliance,” many surveys measure confidence rather than asking directly about trust. As illustrated in Figure 1.4, Harris Poll data on confidence in the U.S. Congress shows the bleakest trend. Except for 1985, when the Congress protected Social Security from cuts under Reagan, and the extended period of economic growth leading up to the dot-com crash in 2000, the public's confidence in Congress has been in steady decline. In the most recent data, less than 10 percent of people said they had a great deal of confidence in Congress.

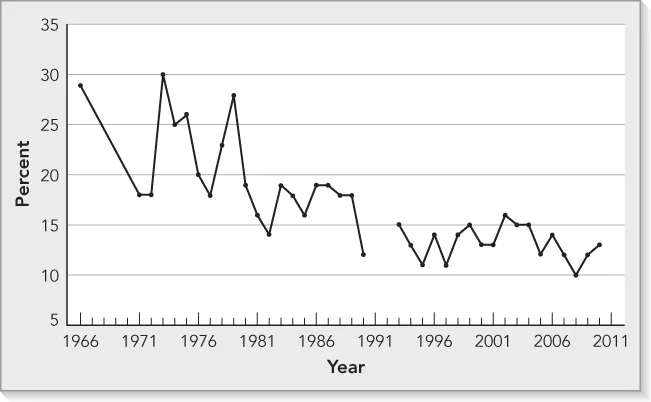

Given the low generalized trust scores and low scores on trust in Congress, we would hope that people can at least trust where they get their information, the press. Unfortunately, according to the Harris Poll, the long-term U.S. trend for confidence in the press also shows declines (see Figure 1.5).10 Trust has declined since 1966, with the exception of two periods when there was a positive bounce: coverage of Watergate in the mid-1970s and of the Iran hostage crisis in the late 1970s into 1980. In 2009, a Pew Research Center survey that asked directly about bias and accuracy showed rising perceptions that the media is biased in its reporting.11

Data on trust in business are even bleaker. The Harris Poll data on confidence in business in the United States is shown in Figure 1.6. Starting at a high of 55 percent in 1966, scores since 2008 are trending at or below 15 percent of people who have a great deal of confidence in business. The only periods when scores increased were from 1992 to 2000, when there were eight years of above-average GDP growth, and during the mania leading up to the dot-com bust, 2000 to 2002. The 2009 Edelman Trust Barometer, which is a global measure, showed that trust in business declined across the globe after the financial crisis. Across twenty countries, 62 percent of respondents trusted business less than the year before.12 In another Edelman survey of more than four thousand p...