eBook - ePub

Improving Crop Productivity in Sustainable Agriculture

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Improving Crop Productivity in Sustainable Agriculture

About this book

An up-to-date overview of current progress in improving crop quality and quantity using modern methods. With a particular emphasis on genetic engineering, this text focusses on crop improvement under adverse conditions, paying special attention to such staple crops as rice, maize, and pulses. It includes an excellent mix of specific examples, such as the creation of nutritionally-fortified rice and a discussion of the political and economic implications of genetically engineered food.

The result is a must-have hands-on guide, ideally suited for the biotech and agro industries.

The result is a must-have hands-on guide, ideally suited for the biotech and agro industries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Improving Crop Productivity in Sustainable Agriculture by Narendra Tuteja,Sarvajeet S. Gill,Renu Tuteja in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Climate Change and Abiotic Stress Factors

Chapter 1

Climate Change and Food Security

Abstract

The Green Revolution ushered in the 1960s brought unprecedented transformation in agricultural production, productivity, food security, and poverty reduction. But, it has now waned. The numbers of hungry, undernourished, and poor remain stubbornly high. Moreover, the natural agricultural production resources, particularly water and land, have shrunk and degraded. The problem has further exacerbated by the global climate change and extreme weather fluctuations widely depressing agricultural yields, increasing production instability, and degrading natural resources. If the change is not managed adequately, the agricultural yields will drop by up to 20% by the year 2050 and the national GDP will erode annually at least by 1%. A series of adaptation and mitigation pathways involving business unusual have been suggested toward developing climate smart agriculture by increasing agricultural resilience to climate change through integrating technology, policy, investment, and institutions with special reference to the resource poor, women, and other more vulnerable people.

1.1 Background and Introduction

Toward the year 2050, the world population is projected to stabilize at around 9.2 billion. In order to adequately feed this population, the global agriculture must double its food production, and farm productivity would need to increase by 1.8% each year – indeed a tall order. On the other hand, the natural resources – the agricultural production base, especially land, water, and biodiversity – are fast shrinking and degrading. For instance, by 2025, 30% of crop production will be at risk due to the declining water availability. Thus, in order to meet the ever-intensifying demand for food and primary production, more and more is to be produced from less and less of the finite natural and nonrenewable resources.

The challenges of attaining sustainably accelerated and inclusive growth and comprehensive food security have been exacerbated by the global climate change and extreme weather fluctuations. The global warming due to rising concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) causing higher temperature, disturbed rainfall pattern causing frequent drought and flood, sea level rise, and so on is already adversely impacting productivity and stability of production, resulting in increased vulnerability, especially of the hungry and resource-poor farmers, and is a growing threat to agricultural yields and food security. World Bank projects that the climate change will depress crop yields by 20% or more by the year 2050. Livestock and fish production will likewise be impacted. Pathogen virulence, disease incidences, pest infestations, epidemic breakouts, and biotic stresses in general are predicted to intensify.

The impact of the climate change will vary across ecogeographic and demographic domains. As projected, the bulk of the population increase will materialize in developing countries. Most of these are agriculture based, and several of them are food deficit. Moreover, these countries have high concentration of smallholder resource-poor farmers and their agriculture is predominantly rainfed, which is inherently low yielding and vulnerable to weather fluctuations. In such countries, sustained and accelerated agricultural growth is fundamental not only to achieving food security but also to generating economic growth and opportunity for overall livelihood security.

India will be the most populous country in the world by 2050, with a projected population of over 1.5 billion, and will need to double its food production by then to ensure its food security. The country was able to overcome its food crisis and insecurity through ushering in the Green Revolution in the mid-1960s. Between 1965 and 1995, the food and agriculture production and productivity had more than doubled and the intensity of hunger and poverty had halved [1]. This revolution was largely due to the synergy of technology, policies, services, farmers' enthusiasm, and strong political will. However, the Green Revolution has now waned. During the past decade or so, while the overall national GDP had registered a high growth rate of 7–9%, the agricultural growth had gone sluggish (although recovered lately).

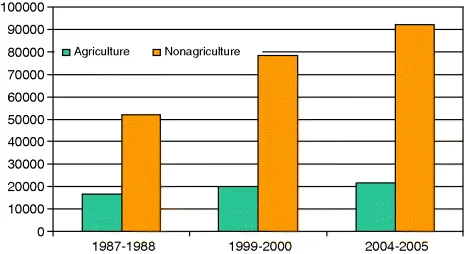

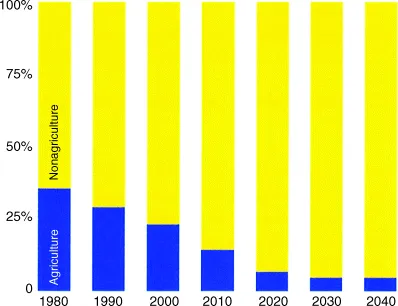

Unethical as it is, the country is still home to almost one-fourth of the world's hungry and poor, and over 40% of our children are undernourished. The income gap between farmers and nonfarmers has widened rather unacceptably, farmers' income being about one-fifth of that of the nonfarmers (Figure 1.1). This is primarily due to the steadily declining share of agriculture in GDP while the intensity of dependence on agriculture for livelihoods has remained high. The agriculture's share in GDP fell from about 35% in 1980 to 15% in 2010, and is expected to fall to 5% in 2040 (Figure 1.2), whereas in 2010 over 50% of the population was dependent primarily on agriculture.

Figure 1.1 Per worker GDP in agriculture and nonagriculture sectors, Rs. at 1999–2000 prices.

(Source: Ref. [2].)

Figure 1.2 Agriculture's share in GDP steadily declining.

(Source: Refs [3, 4].)

In an agriculturally important country like ours, agriculture is the main driver of agrarian prosperity and comprehensive food and nutritional security. The past Five-Year Plans have been aiming at an agricultural growth rate of 4% and above to achieve a balanced overall GDP growth rate of about 8–9%. But, we have not been able to achieve the targeted growth in the agricultural sector, being 3.3% during 1980–2010 and only 2.3% during the decade ending 2010. The coefficient of variation (CV) of the agricultural growth has been high and, if not managed, will further increase with the increasing volatilities caused due to climate change. The XII Plan also targets an overall agricultural output growth of 4.0–4.5% coupled with inclusiveness and gender sensitivity. A business unusual rooted in the principles of ecology, environment, economics, and equity is called for ensuring sustained and enhanced livelihood security of our people in face of the fast changing climate.

1.2 State of Food Security

The number of undernourished people in the world had been increasing for a decade or so and the number of hungry for the first time had crossed the 1 billion mark in 2008–2009 [2], but the number came down to 925 million in 2009–2010. Nearly all hungry people were from developing countries. The gains made in the 1980s and early 1990s in reducing chronic hunger have been lost and the hunger reduction targets of the Millennium Development Goal 1 (MDG1) as well as of the World Food Summit (WFS) remain elusive. The soaring food prices of 2007–2008 had drawn the poor farther from food, resulting in the unusual increase in the number and even proportion of undernourished. Despite the fall in international food and fuel prices starting in the late 2008, the prices in domestic markets remained 15–25% higher in real terms than the trend level – continuing the distress for the poor. High food inflations and the associated household food security have been recurrent features in India.

The continued neglect of agriculture during the past decades had denied hundreds of millions of people access to adequate food and has kept them below the poverty line. Globally, as also in India, the hunger and poverty incidences are mirror images (Table 1.1) and cause and consequence of each other. The rapid increase in the number of hungry and poor in the recent years reveals that food, fuel, and economic crises arise from the fragility of present food systems and livelihood security programs. Necessary structural adjustment and macroeconomic stabilization policies should be designed to minimize the impact of the shocks, particularly through enhanced investment in agriculture (including nonfarm rural activities and employment), expanding safety nets and social assistance programs, and, of course, improving governance.

Table 1.1 Poverty ($1.25 a day or less) and hunger levels in the developing world.

Source: Ref. [5].

| Region | % Poverty | % Hunger (undernourished) |

| Asia-Pacific | 27 | 17 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 8 | 10 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 51 | 32 |

| Total developing countries | 29 | 20 |

In India, as mentioned earlier, the Green Revolution had transformed the country from the status of a food-deficit country to a food self-sufficient nation (at macro level). Per caput dietary energy supply (DES) increased from 2370 kcal/day in 1990–1992 to 2440 kcal/day in 2001–2003, and prevalence of undernourishment in total population decreased correspondingly from 25 to 20%. Between 1993/1994 and 1999/2000, 58 million individuals came out of the poverty trap, the number of poor dropping from 317 million to 259 million. Other livelihood indicators such as literacy rate and longevity also increased significantly. Life expectancy at birth in 2005/2006 was over 63 and 66 years, respectively, for males and females against 58 and 59 years in 1986–1991 [3].

Despite India's national level food self-sufficiency and security, the number of food insecure people in India has remained stubbornly high, in recent years hovering around 245 million, one-fourth of the world's food insecure people. In fact, during 2007–2010, the number of hungry in the country, as in the world as a whole, had increased due to soaring food prices. In percentage term, however, food insecurity in India had reduced from 25% in 1990–1992 to 20% in 2001–2003, but in recent years has increased to 21% (Table 1.2). The record food grain production of over 230, 240, and 250 million tons during the years 2009–2010, 2010–2011, and 2011–2012, respectively, should have improved the situation, which should be known from the latest household survey reports. In any case, one-fifth to one-fourth of our people are still hungry and poor.

Table 1.2 Number and percentage of undernourished people in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Climate Change and Abiotic Stress Factors

- Part II: Methods to Improve Crop Productivity

- Part III: Species-Specific Case Studies

- Index