![]()

CHAPTER 1

CAMPUS PLANNING

David J. Neuman, FAIA, LEED BD + C

OVERVIEW

Campus planning, architecture, and landscape are critical topics at every university and college with a physical setting, for three important reasons:

- They create the actual environment that supports the mission and goals of the institution.

- They define the tangible identity that the institution portrays to its alumni, faculty, students (both current and future), and the general public.

- They assist in portraying the level of sustainability commitment made by the institution.

In short, an academic institution's campus is a critical component of its very existence and survival. This volume is dedicated to translating this important fact into practical terms at the levels of planning, design, and implementation. The chapter authors have each contributed to the phenomenon known as the campus through specific plans, buildings, and landscapes, each of which has in its own way contributed to the further development of this unique environment.

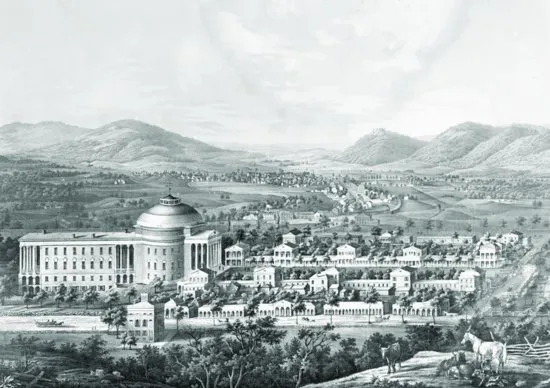

While designing the University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson described his goal as the creation of an “Academical Village” (see Figure 1.1). This term expressed Jefferson's own views on education and planning, but it also summarizes a basic trait of American higher education from the colonial period to the twenty-first century: the conception of colleges and universities as communities in themselves—in effect, as cities in microcosm. This reflects educational patterns and ideals which, although derived principally from Europe, have developed in distinctively American ways.

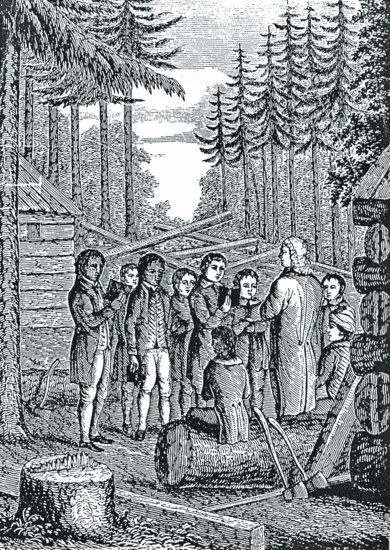

Campuses have their origins in the Western tradition of the Greek agora and in the Socratic approach of open debate in the public realm. The term campus itself was derived from the Greek terminology for a “green” or open landscaped area, and later, the Roman military “camp” of well-planned order. At once, the concept represents a paradox of freedom and control that continues to this day. Although the Greeks may have viewed the campus as a setting to spur the commerce of ideas, the Romans saw its order in terms of colonization and a way to bring their brand of civilization to the conquered “barbarians.” This approach is not unlike that of the early British colonists wanting to establish colleges in the fledgling communities in the American wilderness for instruction of not only their own children but also the native population after it had been “pacified” (see Figure 1.2).

The new colleges symbolized both a continuation of cultural roots and a belief in the future of the pioneering spirit. The campus itself became the symbol or icon of the college and, later, the university.

Although the overall character of a university's physical plant can be simply a result of growth and change, a well-functioning and icon-laden campus results only when it is carefully planned and keenly managed. The qualities of such a place may be described as follows:

- Enduring planning framework

- Compelling landscape character

- Context-sensitive architecture

- Consistent perimeter treatment

- Carefully managed interface among all of these elements

The key is to incorporate these principles rigorously in every decision related to campus planning, from small to large. It is this “sense of place” in its entirety that makes for a campus's intelligibility, functionality, and overall aesthetic. Thus, relatively simple matters, such as maintaining a consistent sign system or a standard exterior light fixture, are important components to the appearance and sense of order of the campus. Some have argued that the campus itself has transcended into the realm of art. “Unlike the two-dimensional art of painting, the three-dimensional art of sculpture, and architecture, in which the fourth dimension is function, a campus has a fifth dimension: planning. The well-planned campus belongs among the most idyllic of man-made environments and deserves to be evaluated by the same criteria applied to these other works of art,” wrote Thomas Gaines in 1991.

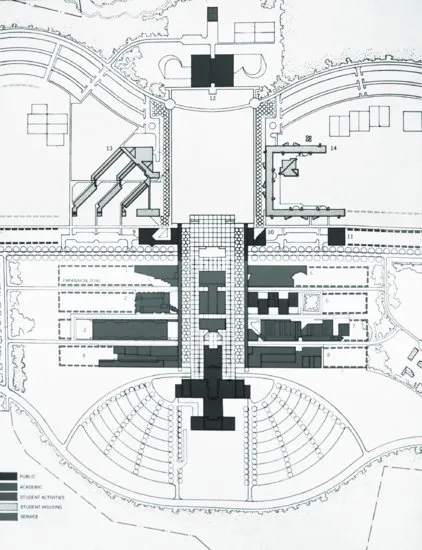

The campus is not just leftover spaces between buildings. It is, in fact, a series of designed places that reflect the values of an institution's wishes to be known for. It is a culturally dynamic, complex landscape setting. The campus must be a place that feels safe, encourages participation, enhances social interaction and appeals to students, faculty, staff and visitors on many levels [see Figure 1.3].

—Dayton Reuter, State University of New York

Those who carry on the mundane daily activities of operating and (re)developing the typical campus may balk at this statement; however, others have for years asserted the campus's role as utopia. This role carries with it not only the expectation of striving for physical perfection but also the spiritual sense of enduring faith in human “improvement.” This serious responsibility was once shouldered by our cities, but seemingly has now been lost in the postmodern era of globalization and exurban development.

A public or private institution such as a college or university, occupying its own tract of land . . . is peculiarly well situated to reap the inestimable fruits of forethought and skill in planning. Nowhere is it more essential to have the physical plant beautiful and well-knit together; nowhere should it be more feasible to enlist the careful thought of well-trained minds, to weigh and reconcile all component parts, to profit by the past, to measure accurately the present, to forecast the future as well as it can be forecast. . . . [We] have called this kind of planning an art; it is also a science.

—Charles Z. Klauder and Herbert C. Wise, 1929

Can campuses reach for such high ground? Certainly, aspirations to the utopian can be read into works ranging from Klauder and Wise's College Architecture in America (1929) to Architectural Planning of the American College by Larson and Palmer (1933) to Paul V. Turner's seminal work, Campus: An American Planning Tradition (1984), to American Place by M. Perry Chapman (2006). Moreover, Robert A. M. Stern's Pride of Place: Building the American Dream (1986) and Richard P. Dober's series of campus-related books (1962–2000) place the American campus squarely in this role as a model for human settlement.

The result of this careful planning and execution by means of the campus landscape and its buildings is often assumed to be at best a didactic environment. In 1923, the Commission on Architecture of the Association of American Colleges asserted that “a grouping of buildings, on a properly designed campus, constructed in accordance with simple and chaste architectural standards, has an art and a life value which the students . . . will assimilate unconsciously. . . . [Therefore,] it is possible for every college, even with limited means at its disposal, to contribute to the elevation of life by careful attention to its campus program.”

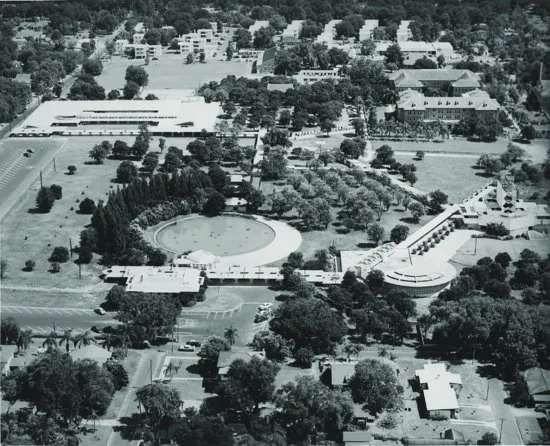

Although Jefferson, his confidants Benjamin Latrobe and William Thornton, and many others have shared this concept, there is perhaps no stronger example than in the development of the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed Florida Southern College campus, which its longtime president, Ludd Spivey, described in part in 2001 as “[a] great education temple in Florida” (see Figure 1.4).

Wright himself labored on this project for more than 20 years, some of the time w...