eBook - ePub

Stem Cells in Craniofacial Development and Regeneration

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stem Cells in Craniofacial Development and Regeneration

About this book

Stem Cells, Craniofacial Development and Regeneration is an introduction to stem cells with an emphasis on their role in craniofacial development. Divided into five sections, chapters build from basic introductory information on the definition and characteristics of stem cells to more indepth explorations of their role in craniofacial development. Section I covers embryonic and adult stem cells with a focus on the craniofacial region, while sections II-IV cover the development and regeneration of craniofacial bone, tooth, temporomandibular joint, salivary glands and muscle. Concluding chapters describe the current, cutting-edge research utilizing stem cells for craniofacial tissue bioengineering to treat lost or damaged tissue.

The authoritative resource for dentistry students as well as craniofacial researchers at the graduate and post-graduate level, Stem Cells, Craniofacial Development and Regeneration explores the rapidly expanding field of stem cells and regeneration from the perspective of the dentistry and craniofacial community, and points the way forward in areas of tissue bioengineering and craniofacial stem cell therapies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stem Cells in Craniofacial Development and Regeneration by George T.J. Huang, Irma Thesleff, George T.J. Huang,Irma Thesleff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Cell Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Development and Regeneration of Craniofacial Tissues and Organs

Chapter 1: Molecular blueprint for craniofacial morphogenesis and development

Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Kansas City, Missouri, and University of Kansas Medical Center Kansas City Kansas

1.1 Introduction

The vertebrate head is a sophisticated assemblage of cranial specializations, including the central and peripheral nervous systems and viscero-, chondro-, and neurocraniums, and each must be properly integrated with musculature, vasculature, and connective tissue. Anatomically, the head is the most complex part of the body, and all higher vertebrates share a common basic plan or craniofacial blueprint that is established during early embryogenesis. This process begins during gastrulation and requires the coordinated integration of each germ layer tissue (i.e., ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) and its derivatives in concert with the precise regulation of cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation for proper craniofacial development (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). For example, the appropriate cranial nerves must innervate the muscles of mastication, which, via tendon attachment to the correct part of the mandible, collectively articulate jaw opening and closing. In addition, each of these tissues must be sustained nutritionally and remain oxygenated and thus are intimately associated with the vasculature as part of a fully functioning oral apparatus.

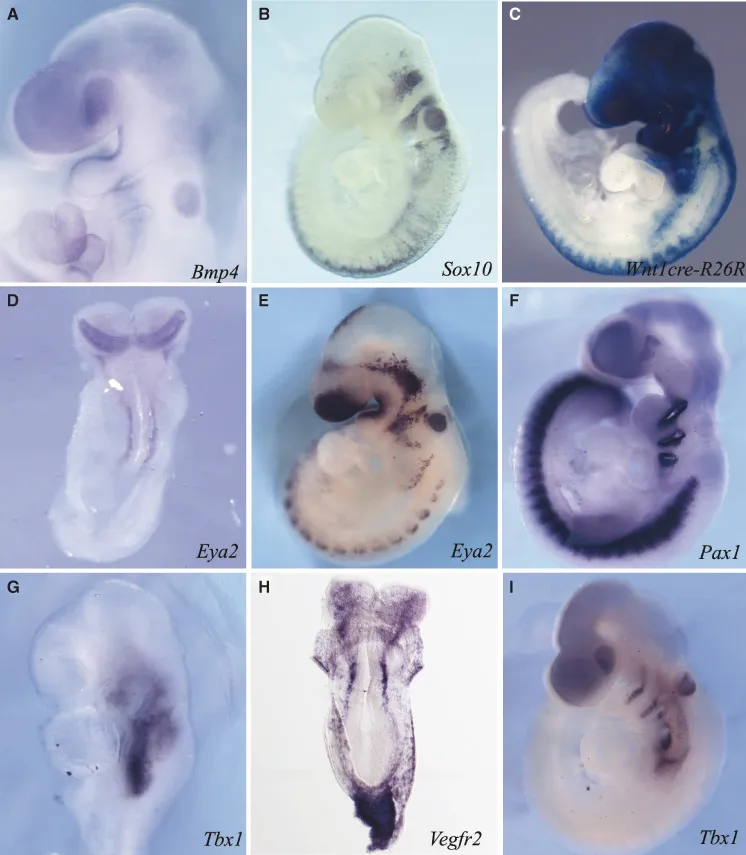

Figure 1.1 Specification of ectoderm, neural crest, placodes, mesoderm, and endoderm. In situ hybridization (A, B, D–I) or lacZ staining (C) of E8.5–9.5 mouse embryos as indicators of differentiation of ectoderm (A, Bmp4), neural crest cells (B, Sox10; C, Wnt1cre-R26R), ectodermal placodes (D and E, Eya2), endoderm (F, Pax1), mesoderm (G and I, Tbx1), and endothelial cells (H, Vegfr2).

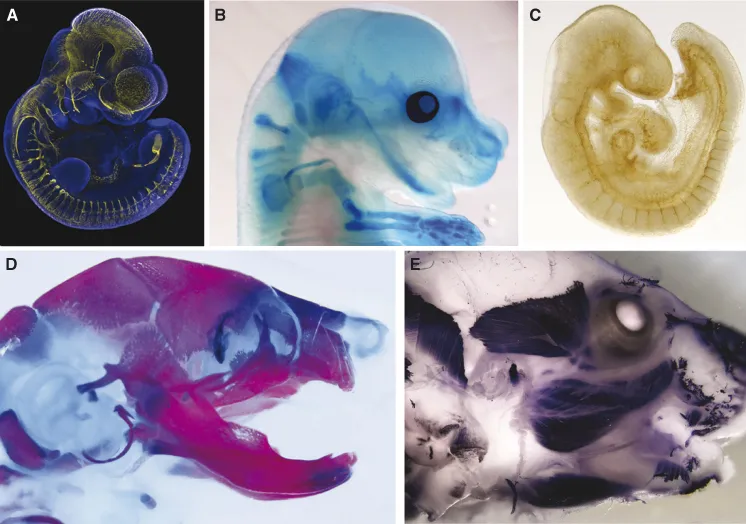

Figure 1.2 Formation of the nervous system, skeleton, musculature, and vasculature. Immunostaining (A, C, and E) and histochemical stainining (B and D) as indicators of formation of the peripheral nervous system (A, E10.5, Tuj1), cartilage (B, E15.5, alcian blue), vasculature (C, E9.5, PECAM), skeletal bone and cartilage (E18.5, alizarin red/alcian blue), and muscle (E18.5, MHC).

Given this complexity, it is not surprising that a third of all congenital defects affect the head and face (Gorlin et al., 1990). Improved understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of head and facial birth defects and their potential prevention or repair depends on a thorough appreciation of normal craniofacial development. But what are the signals and mechanisms that establish each of these individual cells and tissues and govern their differentiation and integration? In this chapter specification of the major cell lineages, tissues, and structures that establish the blueprint for craniofacial development is described, as well as the interactions and integration that are essential for normal functioning throughout embryonic as well as adult life.

Craniofacial development begins during gastrulation, which is the process that generates a triploblastic organism. During gastrulation, cells from the epiblast (embryonic ectoderm) are allocated to three definitive germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Formation of the mesoderm and endoderm is accomplished by morphogenetic cell movement that comprises ingression of epiblast cells through the primitive streak (a site of epithelial–mesenchyme transition), followed by organization of ingressed mesoderm progenitors into a mesenchymal layer and incorporation of the endoderm progenitors into a preexisting layer of visceral endoderm (Arkell and Tam, 2012). Notably, a general axial registration exists between these progenitor germ layer tissues as they are established and influences their differentiation (Trainor and Tam, 1995a). These relationships and the tissue boundaries they create are often maintained throughout embryogenesis and into adult life and are critically important for proper vertebrate head and facial function. Thus, gastrulation and generation of the three germ layers create the principal building blocks of the head and face (Arkell and Tam, 2012). The ensuing morphogenetic movements that bring these tissue components to their proper place in the body plan establish the initial blueprint. Subsequent morphogenetic events continue to build on this scaffold until the fully differentiated structures emerge that define the head and face.

1.2 Ectoderm: Neural Induction

Motor coordination, sensory perception, and memory all depend on precise, complex cell connections that form between distinct nerve cell types within the central nervous system. Development of the central nervous system occurs in several steps. The first step, neural induction, generates a uniform sheet of neuronal progenitors called the neural plate. Neural induction is followed by neurulation, a process in which the two halves of the neural plate are transformed into a hollow tube. Neurulation is accompanied by regionalization of the neural tube anterior–posteriorly into the brain and spinal cord and dorsoventrally into neural crest cells and numerous classes of sensory and motor neurons. Proper development of the central nervous system requires finely balanced control of cell specification and proliferation, which is achieved through the complex interplay of multiple signaling pathways. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), retinoic acid (RA), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and Hedgehog (Hh) proteins are a few key factors that interact to pattern the developing central nervous system.

Neural induction constitutes the first step in ectoderm differentiation and essentially resolves ectoderm progenitors into neuroectoderm versus surface ectoderm. A landmark experiment in amphibian embryos revealed that differentiation of uncommitted ectoderm into neuroectoderm depended on the underlying mesoderm (Spemann and Mangold, 1924). Transplantation of this mesoderm, called the blastopore lip, or Spemann's organizer, induced the formation of a duplicated body axis, including an almost complete second nervous system. The discovery of a number of secreted molecules expressed by the organizer in amphibian and avian embryos provides a molecular mechanism underpinning the process of neural induction. The most important molecules include noggin (Lamb et al., 1993), chordin (Sasai et al., 1994), and follistatin (Hemmati-Brivanlou et al., 1994), which mediate neural induction by binding to and inhibiting a subset of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (reviewed by Sasai and De Robertis, 1997). Each of these secreted factors has potent neural-inducing ability when added to Xenopus ectodermal explants and mimics the capacity of the organizer to induce and pattern a secondary axis. Interestingly, during Xenopus gastrulation, Bmp4 expression is repressed by signals from the organizer in the portion of the ectoderm fated to become the neural plate (Fainsod et al., 1994). Therefore, inhibition of BMP signaling represses epidermal fate and induces neural differentiation. Consistent with this idea, single ectoderm cells taken from gastrula-stage Xenopus embryos and cultured in the absence of any additional factors (e.g., BMP4) will differentiate into neural tissue. This prompted the idea of a “default model” for neural induction in which ectodermal cells, by default, adopt a neural fate when removed from the influence of extracellular signals during gastrulation (Wilson and Hemmati-Brivanlou, 1995, 1997). However, difficulties arose when attempts were made to extrapolate this model to amniotes and mammals.

In chick embryos, the organizer (Hensen's node) expresses the BMP inhibitors Noggin and Chordin, yet neither Noggin nor Chordin induces neural cell differentiation in avian embryos (Streit et al., 1998). Furthermore, their temporal expression does not coincide with neural induction (Streit and Stern, 1999b). In addition, a neural plate still forms in chick, frog, zebrafish, and mouse embryos, despite surgical removal of the organizer (Wilson et al., 2001), and gene-targeting experiments in mouse have shown that neural differentiation occurs in the absence of BMP inhibitors, arguing that BMP signaling is not required for neural induction (Matzuk et al., 1995; McMahon et al., 1998; Bachiller et al., 2000). The evolution of fundamentally different molecular mechanisms for specifying neural fate in amniotes versus anamniotes seems unlikely, and in agreement with this, the avian organizer can substitute for the Xenopus blastopore lip (Kintner and Dodd, 1991). Avian neural induction appears to be initiated by FGF signals emanating from the precursors of Hensen's node (Streit et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2000). Fgf8 is expressed during gastrulation in the anterior of the primitive streak, including the node; however, its expression is downregulated as the node begins to lose its neural-inducing ability. Consistent with this, inhibition of FGF signaling downregulates the expression of neural plate markers (Streit et al., 2000). Thus, one possible function for FGF signaling may be to attenuate BMP signaling in prospective neural cells. In support of this idea, inhibition of FGF results in maintenance of Bmp4 and Bmp7 expression, both of which are normally downregulated in epiblast cells of prospective neural character. This implies a role for FGF in repressing BMP signaling. Thus, as in Xenopus, acquisition of neural fate requires the repression of Bmp activity, while epidermal cell fate requires maintenance of Bmp expression (Fig. 1.1A). However, neither FGF signaling alone or in combination with BMP antagonists is sufficient for the induction of Sox2 or later neural markers (Harland, 2000; Streit et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2000). WNT proteins are one of the additional signals required for the regulation of neural versus epidermal fates (Wilson et al., 2001). In chick embryonic ectoderm, lateral or prospective epidermal tissue expresses Wnt3 and Wnt8, whereas medial or prospective neural tissue does not. The lack of exposure to WNT signaling in the medial ectoderm permits Fgf8 expression, which in turn represses BMP signaling, specifying neural fate. Conversely, high levels of WNT signaling in lateral epiblast cells inhibit FGF signaling, allowing for BMP activity, which in turn directs cells to an epidermal fate (Wilson et al., 2001).

Thus, vertebrate neural induction involves the coordinated interaction of three different signaling pathways—FGFs, BMPs, their associated antagonists, and WNTs—all of which play significant but distinct roles in the differentiation of neural versus epidermal fate. Notably, a key conserved feature among vertebrates is the exclusion of Bmp expression from the neural-induced territory.

1.3 Ectoderm: Neurulation

Neural induction is followed by neurulation, the process by which the neural plate is transformed into a hollow neural tube. In amphibians, mice, and chicks, the neural tube forms through uplifting of the two halves of the neural plate and their fusion at the dorsal midline. In contrast, in fish, formation of the neurocele occurs via cavitation of the neural plate. The neural tube then becomes partitioned via differential cell proliferation into a series of swellings and constrictions that define the major compartments of the adult brain: forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon). The forebrain becomes further regionalized anteriorly into the telencephalon and posteriorly into the diencephalon. The telencephalon develops into the cerebral hemispheres, and the diencephalon gives rise to the thalamic and hypothalamic brain regions. Similar to the forebrain, the hindbrain becomes subdivided further. The anterior portion forms the metencephalon, which gives rise to the cerebellum, the specific part of the brain responsible for coordinating movements, posture, and balance. The posterior portion forms the myelencephalon, which generates the medulla oblongata, the nerves of which regulate respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular movements. In contrast to the forebrain and hindbrain, the midbrain is not subdivided further. However, the lumen of the midbrain gives rise to the cerebral aqueduct.

An important question relates to how cells in the neural plate become regionalized and specified into forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord domains, since immediately following induction, the neural plate is assumed to have a uniformly rostral character. Is there a mechanism that can account for the anterior–posterior specification of individual cells along the entire neural axis? In chick embryos, medial epiblast cells in blastula-stage embryos generally express Sox2, Sox3, Otx2, and Pax6, a combination of markers characteristic of the forebrain. In addition, these cells do not express En1/2, Krox20, or Hoxb8, which are typical markers of the midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord, resp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Development and Regeneration of Craniofacial Tissues and Organs

- Part II: Stem Cells and their Niches in Craniofacial Tissues

- Part III: Stem Cell-Mediated Craniofacial Tissue Bioengineering

- Index