![]()

Part I

Laser Fundamentals

![]()

1

Laser Basics

1.1 Introduction

Although lasers were confined to the premises of prominent research centres such as the Bell laboratories, Hughes research laboratories and major academic institutes such as Columbia University in their early stages of development and evolution, this is no longer the case. Theodore Maiman demonstrated the first laser five decades ago in May 1960 at Hughes research laboratories. The acronym ‘laser’, Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation, first used by Gould in his notebooks is a household name today. It was undoubtedly one of the greatest inventions of the second half of the 20th century along with satellites, computers and integrated circuits; its unlimited application potential ensures that it continues to be so even today. Although lasers and laser technology are generally applied in commercial, industrial, bio-medical, scientific and military applications, the areas of its usage are multiplying as are the range of applications in each of these categories.

This chapter, the first in Laser basics, is aimed at introducing the readers to operational fundamentals of lasers with the necessary dose of quantum mechanics. The topics discussed in this chapter include: the principles of laser operation; concepts of population inversion, absorption, spontaneous emission and stimulated emission; three-level and four-level lasers; basic laser resonator; longitudinal and transverse modes of operation; and pumping mechanisms.

1.2 Laser Operation

The basic principle of operation of a laser device is evident from the definition of the acronym ‘laser’, which describes the production of light by the stimulated emission of radiation. In the case of ordinary light, such as that from the sun or an electric bulb, different photons are emitted spontaneously due to various atoms or molecules releasing their excess energy unprompted. In the case of stimulated emission, an atom or a molecule holding excess energy is stimulated by a previously emitted photon to release that energy in the form of a photon. As we shall see in the following sections, population inversion is an essential condition for the stimulated emission process to take place. To understand how the process of population inversion subsequently leads to stimulated emission and laser action, a brief summary of quantum mechanics and optically allowed transitions is useful as background information.

1.3 Rules of Quantum Mechanics

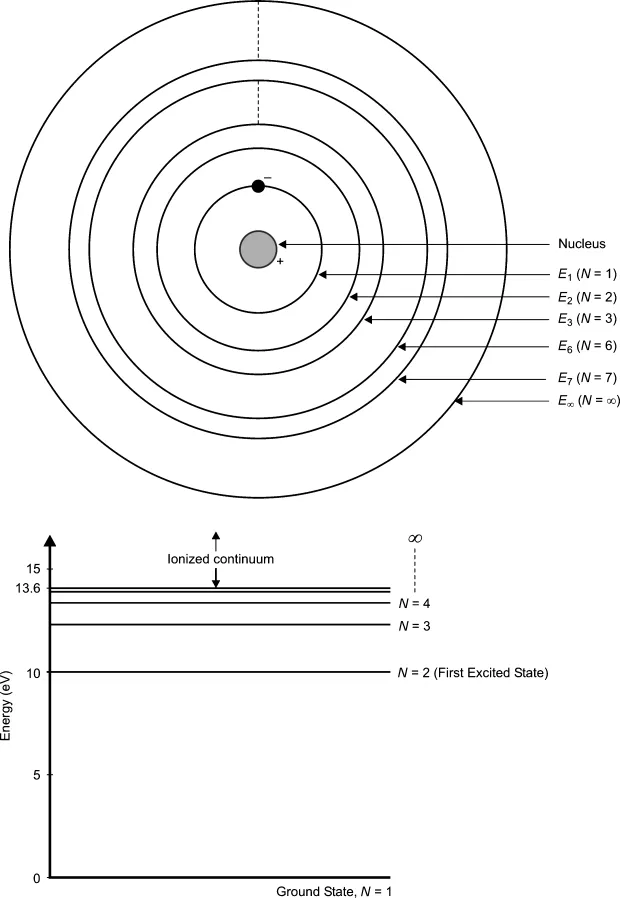

According to the basic rules of quantum mechanics all particles, big or small, have discrete energy levels or states. Various discrete energy levels correspond to different periodic motions of its constituent nuclei and electrons. While the lowest allowed energy level is also referred to as the ground state, all other relatively higher-energy levels are called excited states. As a simple illustration, consider a hydrogen atom. Its nucleus has a single proton and there is one electron orbiting the nucleus; this single electron can occupy only certain specific orbits. These orbits are assigned a quantum number N with the innermost orbit assigned the number N = 1 and the subsequent higher orbits assigned the numbers N = 2, 3, 4…outwards. The energy associated with the innermost orbit is the lowest and therefore N = 1 also corresponds to the ground state. Figure 1.1 illustrates the case of a hydrogen atom and the corresponding possible energy levels.

The discrete energy levels that exist in any form of matter are not necessarily only those corresponding to the periodic motion of electrons. There are many types of energy levels other than the simple-to-describe electronic levels. The nuclei of different atoms constituting the matter themselves have their own energy levels. Molecules have energy levels depending upon vibrations of different atoms within the molecule, and molecules also have energy levels corresponding to the rotation of the molecules. When we study different types of lasers, we shall see that all kinds of energy levels – electronic, vibrational and rotational – are instrumental in producing laser action in some of the very common types of lasers.

Transitions between electronic energy levels of relevance to laser action correspond to the wavelength range from ultraviolet to near-infrared. Lasing action in neodymium lasers (1064 nm) and argon-ion lasers (488 nm) are some examples. Transitions between vibrational energy levels of atoms correspond to infrared wavelengths. The carbon dioxide laser (10 600 nm) and hydrogen fluoride laser (2700 nm) are some examples. Transitions between rotational energy levels correspond to a wavelength range from 100 microns (μm) to 10 mm.

In a dense medium such as a solid, liquid or high-pressure gas, atoms and molecules are constantly colliding with each other thus causing atoms and molecules to jump from one energy level to another. What is of interest to a laser scientist however is an optically allowed transition. An optically allowed transition between two energy levels is one that involves either absorption or emission of a photon which satisfies the resonance condition of ΔE = hν, where ΔE is the difference in energy between the two involved energy levels, h is Planck's constant (= 6.626 075 5 × 10−34 J s or 4.135 669 2 × 10−15 eV s) and ν is frequency of the photon emitted or absorbed.

1.4 Absorption, Spontaneous Emission and Stimulated Emission

Absorption and emission processes in an optically allowed transition are briefly mentioned in the previous section. An electron or an atom or a molecule makes a transition from a lower energy level to a higher energy level only if suitable conditions exist. These conditions include:

1. the particle that has to make the transition should be in the lower energy level; and

2. the incident photon should have energy (=hν) equal to the transition energy, which is the difference in energies between the two involved energy levels, that is, ΔE = hν.

If the above conditions are satisfied, the particle may make an absorption transition from the lower level to the higher level (Figure 1.2a). The probabili...