- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Mood Disorders

About this book

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Mood Disorders, 2/e reflects the important and fast-changing advancements that have occurred in theory and practice in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. There is no other current reference that gathers all of these developments together in a single book

- Every chapter is updated to reflect the very latest developments in theory and practice in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders

- Includes additional chapters which cover marital and family therapy, medical disorders and depression, and cross-cultural issues

- Contributions are from the world's leading authorities, and include psychiatrists and clinical psychologists with experience in both research and in practice

- Focuses on innovations in science and clinical practice, and considers new pharmacological treatments as well as psychological therapies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Mood Disorders by Mick Power in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Unipolar Depression

Unipolar Depression

1

The Classification and Epidemiology of Unipolar Depression

Introduction

In the revised version of this chapter, the original structure has largely been maintained. After all, the principles of classification and the problems it poses for the epidemiology of depression remain the same. However, I have summarized the slow progress toward revision of the ICD and DSM classificatory systems. In the original chapter, I provided illustrative examples of the epidemiology of depression in terms of age, gender, life stress, and childhood antecedents of depression. In the current version, I have, somewhat selectively, updated the account of research in these topics, but have changed the emphasis away from well-established issues such as the effect of gender, and toward the epidemiology of depression in the workplace. This seems particularly relevant in a world where inexorable economic advancement is no longer guaranteed and retrenchment has major effects on work and workers.

Classification and Unipolar Depression

Psychiatric classification is quintessentially a medical procedure. The study of medicine is based on the establishment of separate categories of disorder (illnesses, diseases).1 These are distinguished in terms of particular types of attributes of the people held to be suffering from them. These attributes comprise symptoms (based on self-report) and signs (based on observation). Individual disorders are conceived in terms of concatenations of symptoms and signs, which are termed syndromes. Such syndromes are provisional constructs, whose validity (or otherwise) is then established by using them as the basis of different sorts of theory: etiological theories, and theories of course and outcome, of treatment, and of pathology (Bebbington, 2011; Wing, Mann, Leff, & Nixon, 1978). There is no doubt that the medical approach to malfunction has been a very effective one, generating new knowledge quickly and efficiently by testing out theories of this type (Bebbington, 1997).

Psychiatric disorders are classified in the hope that the classification can provide mutually exclusive categories to which cases can be allocated unambiguously (the process of case identification). The medical discipline of epidemiology is the study of the distribution of diseases (i.e., medical classes) in the population, and is based on categories of this type. It has been a very powerful method for identifying candidate causal factors, and is thus of great interest to psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as to clinicians from other specialties.

The idea of unipolar depression involves the application of this syndromal approach to psychological disturbance, and is therefore primarily a medical concept. However, the distinctiveness of psychiatric syndromes is both variable and limited. Unipolar depression, in particular, resembles, overlaps, and needs distinguishing from other disorders characterized by mood disturbance: anxiety disorders, other depressive conditions, and bipolar mood disorder. The particular problem with bipolar disorder is that its identification depends on the presence of two sorts of episode in which the associated mood is either depressed or predominantly elated. It is distinct from unipolar disorder in a variety of ways (e.g., inheritance, course, and outcome), and the distinction is therefore almost certainly a useful one. However, depressive episodes in bipolar disorder cannot be distinguished symptomatically from those of unipolar depression. As perhaps half of all cases of bipolar disorder start with a depressive episode, this means that unipolar depression is a provisional category—the disorder will be reclassified as bipolar in 5% of cases (Ramana & Bebbington, 1995).

Symptoms and Syndromes

The first stage in the establishment of syndromes is the conceptualization of individual symptoms. Symptoms in psychiatry are formulations of aspects of human experience that are held to indicate abnormality. Examples include abnormally depressed mood, impaired concentration, loss of sexual interest, and persistent wakefulness early in the morning. They sometimes conflate what is abnormal for the individual with what is abnormal for the population, but they can generally be defined in terms that are reliable. Signs (which are unreliable and rarely discriminating in psychiatry, and thus tend to be discounted in diagnosis) are the observable concomitants of such experiences, such as observed depressed mood, or behavior that could be interpreted as a response to hallucinations. Particular symptoms (and signs) often coexist in people who are psychologically disturbed, and this encourages the idea that they go together to form recognizable syndromes. The formulation of syndromes is the first stage in the disease approach to medical phenomena, as syndromes can be subjected to investigations that test out the various types of theories described above.

It is often said, in both medical and lay discourse, that psychiatric disorders are like (or just the same as) disorders in physical medicine. This is not strictly true. Self-reports in general medicine relate to bodily sensation and malfunction in a way that can be linked to pathological processes. Thus the classical progression of symptoms in appendicitis is related straightforwardly to the progression of inflammation from the appendix to the peritoneal lining. Symptoms in psychiatry, in contrast, are essentially based on idiosyncratic mental experiences, with meanings that relate to the social world. Reformulating psychiatric disorders in terms of a supposed biological substrate would therefore result in the conceptualization of a different condition, which would map imperfectly onto the original disorder.

While syndromes are essentially lists of qualifying symptoms and signs, individuals may be classed as having a syndrome while exhibiting only some of the constituent symptoms. Moreover, within a syndrome there may be theoretical and empirical reasons for regarding particular symptoms as having special significance. Other symptoms, however, may be relatively nonspecific, occurring in several syndromes. Even so, clusters of such symptoms may achieve a joint significance. This inequality between symptoms is seen in the syndrome of unipolar depression: depressed mood and anhedonia are usually taken as central, while other symptoms (e.g., fatigue or insomnia) have little significance on their own. This reflects a serious problem with the raw material of human mental experience: it does not lend itself to the establishment of the desired mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive categories that underpin medical classification.

In an ideal world, all the symptoms making up a syndrome would be discriminating, but this is far from true, and decisions about whether a given subject’s symptom pattern can be classed as lying within a syndrome usually show an element of arbitrariness. The result is that two individuals may both be taken to suffer from unipolar depression despite exhibiting considerable symptomatic differences.

This is tied in with the idea of symptom severity: disorders may be regarded as symptomatically severe either from the sheer number of symptoms or because several symptoms are present in severe degree. In practice, disorders with large numbers of symptoms also tend to have a greater severity of individual symptoms. In classifications that rely on relatively few symptoms to establish diagnoses of depressive conditions, the issue of severity may need to be dealt with by including other markers, particularly impairment of social engagement and activity, and disabilities in self-care.

The Limits of Classification

As classification aspires to “carve nature at the joints,” the empirical relationships between psychiatric symptoms create special difficulties of their own. In particular, symptoms are related nonreflexively: thus, some symptoms are common and others are rare, and in general they are hierarchically related, rather than being associated in a random manner. Rare symptoms often predict the presence of common symptoms, but common symptoms do not predict rare symptoms. Deeply (i.e., “pathologically”) depressed mood is commonly associated with more prevalent symptoms such as tension or worry, while in most instances tension and worry are not associated with depressed mood (Sturt, 1981). Likewise, depressive delusions are almost invariably associated with depressed mood, whereas most people with depressed mood do not have delusions of any kind. The consequence is that the presence of the rarer, more “powerful” symptoms indicates a case with many other symptoms as well, and therefore a case that is more symptomatically severe. It is because of this set of empirical relationships between symptoms that psychiatric syndromes are themselves quite largely hierarchically arranged. Thus, schizophrenia is very often accompanied by affective symptoms, although these are not officially part of the syndrome. Likewise, psychotic depression is not distinguished from nonpsychotic depression by having a completely different set of symptoms, but by having extra, discriminating symptoms such as depressive delusions and hallucinations.

Leaky Classes and Comorbidity

The operational criteria set up to identify and distinguish so-called common mental disorders cut across the natural hierarchies existing between symptoms. The consequence is that many people who have one of these disorders also meet the criteria for one or more of the others. This comorbidity has generated much interest, and was even incorporated into the titles of recent major US epidemiological surveys (the National Comorbidity Survey and its replication Kessler, McGonagle, Zhoa, et al., 1994, Kessler et al., 2003). Researchers then divide into two camps: those who think the comorbidity represents important relationships between well-validated disorders, and those who think it arises as an artifact of a classificatory system that is conceptually flawed and fails adequately to capture the nature of affective disturbance.

Depression and the Threshold Problem

The final difficulty with the classification of depression is that it involves imposing a categorical distinction on a set of phenomena that look more like the expression of a continuum. The empirical distribution of affective symptoms in the general population is characteristic: many people have a few symptoms, while few people have many.

For some authorities, this pattern of distribution calls into question the utility of a medical classification. It certainly makes case definition and case finding contentious, as decisions have to be made about the threshold below which no disorder should be identified. People who have few symptoms may still be above this threshold if some of their symptoms are particularly discriminating, but in general the threshold is defined by the number of symptoms. There has always been a tendency in medicine to move thresholds down, particularly as many people who may be regarded by primary care physicians as meriting treatment fall below the thresholds of DSM-IV or ICD-10.

The threshold problem has encouraged a considerable literature relating to subthreshold, subclinical, minor, and brief recurrent affective disorders (Schotte & Cooper, 1999). The tendency to extend the threshold downward is apparent in the establishment of the category of dysthymia, a depressive condition characterized only by its mildness (i.e., a lack of symptoms) and its chronicity. It has, nevertheless, become a study in its own right: it has clear links with major depression presumably because it is relatively easy for someone who already has some depressive symptoms to acquire some more and thereby meet criteria for the more severe disorder.

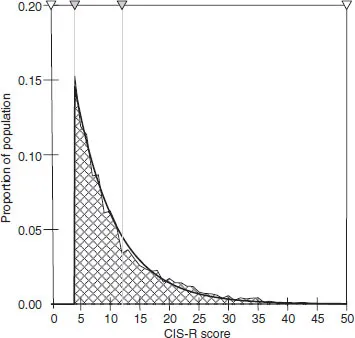

The imposition of a threshold on an apparent continuum would be less arbitrary if it were possible to demonstrate a naturally occurring “step-change” in the distribution. Thus, while the distribution of IQ is largely continuous, Penrose (1963) noted a clear excess of subjects at the bottom of the continuum who are characterized by a distinct and identifiable pathology. Many have argued that no such distinction exists in affective symptoms (Goldberg, 2000; Tyrer, 1985). While it might be possible to create a threshold that represented a step-change in social disability (Hurry, Sturt, Bebbington, & Tennant, 1983), the evidence does, overall, suggest that affective symptoms are distributed more like blood pressure than IQ. Melzer, Tom, Brugha, Fryers, and Meltzer (2002) used symptom data from the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity to test out the smoothness of the distribution. A single exponential curve provided the best fit for the whole population, but there were floor effects that produced deviations at symptom counts from zero to three. Truncation of the data to take account of this provided an excellent fit (Figure 1.1). This was not affected by selecting subgroups characterized by especially high or low prevalence for analysis.

FIGURE 1.1 Proportion of Population by Truncated Range of CIS-R Scores, and Fitted Exponential Curve. Reproduced with permission from Melzer et al. (2002)

It can be concluded from this discussion that the epidemiological literature on depressive disorder will need to be interpreted cautiously. We have disorders that are identified as classes imposed on what is empirically a continuum, and which in any event overlap each other. This is made worse because the classificatory schemes are changed at regular intervals. Moreover, two major schemes exist side-by-side. Added to this is the issue of how the symptoms of common mental disorders can be elicited, identified, and used in order to decide if together they can be said to constitute a case.

Competing Classifications

The indistinctness of psychiatric syndromes and of the rules for deciding if individual disorders meet symptomatic criteria has major implications for attempts to operationalize psychiatric classifications. Two systems have wide acceptance: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Disease (ICD). In the early days, revision of classificatory schemata relied almost wholly on clinical reflection. However, since the classifications are set up primarily for scientific purposes, they should properly be modified in the light of empirical research that permits definitive statements about their utility. The standardized and operationalized classifications now available offer an opportunity for using research in this way, and current attempts to modify them are being based on extensive reviews of the evidence.

In the past, much of the pressure for change originated in clinical and political demands. In particular,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Editor

- List of Contributors

- Foreword to First Edition

- Part I: Unipolar Depression

- Part II: Bipolar Depression

- Part III: General Issues

- Author Index

- Subject Index