![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Why Lubricate Rolling Bearings?

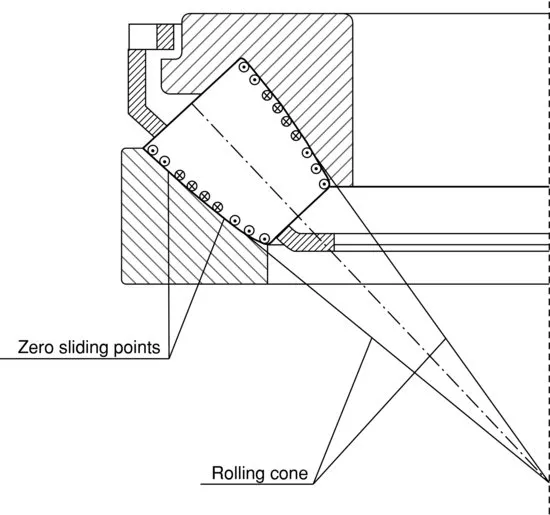

Rolling motion can be used to carry and transmit load while facilitating movement with very low friction and low wear rates, even in the absence of lubrication. The best known example where this is used is the wheel, invented by Mesopotamians in ca. 3500 BC. Lubrication of wheel–road (or later wheel–rail) contact is difficult, but even in the absence of lubrication wear rates are much lower than those of, for example, sledges or sliding shoes. The rolling bearing is based on this principle, although the configuration is more complex since, for carrying a single load, several rolling elements are used, which have a double contact (with the inner-ring and the outer-ring). Unfortunately, even in the apparently rolling contacts, slip occurs. This is partly due to the elastic deformation of the bodies in contact, which flattens the contacts to some extent, and partly due to the kinematics in the bearings. The first effect is usually very small (and can be decreased by using materials with a high elastic modulus). The second effect is more severe. The first effect is dominant in the contacts on tapered and cylindrical roller bearing raceways, which can run at very low friction levels (note that this does not apply to the contacts on the flanges in these bearings). For other bearing types, sliding profiles in the contacts between rolling element and rings typically show just one or two points of pure rolling. Positive slip occurs between these points and negative slip outside these points. This is shown in Figure 1.1 for a thrust spherical roller bearing.

In the absence of lubrication, the surfaces will be in intimate contact, resulting in high friction and wear at the areas where slip occurs. This will produce high stresses close to the surface, leading both to reduction of the fatigue life of the bearing and also to wear.

The occurrence of wear in the slip zones and the absence of wear in the points of pure rolling will produce a nonuniform wear profile across the tracks, leading again to high stresses at the zero-sliding points where less wear has taken place, with a corresponding reduction in the life of the bearing. This does not mean that rolling bearings cannot run in the absence of lubrication, but with no lubrication the service life will be impaired.

Full separation of the surfaces in contact, or ‘full film lubrication’, is preferable. In this case there is virtually no wear and the life of the bearing will be determined by fatigue. If full film conditions are not possible the materials should preferably be ‘incompatible’, meaning that adhesion and ‘welding’ can be avoided. This can be done by using ceramic rolling elements, for example, or by applying a suitable coating (or surface treatment) on one or both surfaces in contact. Due to the local sliding conditions a coating will wear and the service life of the bearing is determined by the wear rate and thickness of the coating. Nevertheless, the relatively short unlubricated life can be increased substantially by this solution. The advantage of using fluid lubrication is its ability to repair itself after shear in the contacts due to its ability to replenish the contacts (a self-healing mechanism). If a sufficient quantity of lubricant is available, this will happen through churning, splashing or will be flow-induced by the geometry of the bearing (by the pumping effect and centrifugal forces). In the case of grease lubrication, it occurs primarily through oil-bleeding, spin, cage distribution and to some extent through a centrifugal force inducing flow in thin lubricant layers.

1.2 History of Grease Lubrication

The word ‘grease’ is derived from the Latin word ‘crassus’ meaning fat. As far back as 1400 BC, both mutton fat and beef fat were used as axle greases in chariots (journal bearings). Early forms of grease lubricants before the 19th century were largely based on natural triglycerides, animal fats and oils, commonly known as ‘grease’ (Polishuk [475]).1 Partial rendering of fats with lime or lye would produce simple greases that were effective as lubricants for wooden axles and simple machinery. Triglycerides are good boundary lubricants that show low coefficients of friction but they show poor oxidative stability at elevated operating temperatures.

After the discovery of oil in the USA (Drake) in 1859, most lubricants were based on mineral oil [450]. The first ‘modern’ greases were lime soaps or calcium soaps, which today are not much used in rolling bearings. They may however be used providing that the temperatures stay low. Later, aluminium and sodium greases were developed, which could accommodate higher temperatures. Until the Second World War only these calcium, sodium and aluminium greases were used.

In the 1930s–1940s new thickeners were discovered for multipurpose greases, based on calcium, lithium and barium [450]. In 1940 the first calcium complex grease and lithium grease patents [182] were issued. Today, over 50% of the market still consists of lithium grease. Aluminium complex greases were developed in the 1950s and lithium complex greases in the 1960s. Polyurea use, started in the 1980s, especially in Japan.

In 1992 a new type of grease was invented by Meijer [414], where the thickener comprises a mixture of a high molecular and low molecular weight polymer of propylene. A grease structure could be obtained through rapid quenching. This type of grease has been successfully tested and is used today in, for example, paper mill bearings [73]. Another example is nanotube grease[271,272].

Grease lubricants are used in a large variety of environments. Operating temperatures for grease lubricated applications range from subzero, −70 °C to temperatures exceeding 300 °C for high temperatures applications. They are also used in vacuum atmospheres encountered by space applications. More often, the operating environment involves wet and humid atmospheres, exposure to salt water and many other types of corrosive agents that affect the performance of rolling bearings and machine elements. The chemical composition of grease lubricants varies considerably to accommodate the large variety of applications and extremes in operating environments. Grease is commonly used for rolling bearing lubrication as a cost-effective and convenient source of lubrication.

1.3 Grease Versus Oil Lubrication

As mentioned above, the longest service life can be obtained if the lubricant film fully separates the contacting surfaces. In a rolling bearing this is achieved through hydrodynamic action where the lubricant is sheared inbetween the roller–ring contacts. Once inside these contacts the viscosity becomes so high, due to the high pressures, that leakage (pressure-driven flow) out of the contact will remain very small. It will be shown later, in Chapter 9, that this film thickness depends on oil viscosity and bearing speed. Obviously, a film can only be maintained if sufficient oil is available. In oil bath lubrication this is not a problem, but in the case of grease lubrication this is more difficult. The lubricating grease will generate a thick film at the beginning of bearing operation, formed by the combination of thickener and base oil. Side flow occurs due to the pressure difference inside the bearing contacts and next to the tracks. There may be very little reflow back into the track and the bearing may suffer from starvation, with thinner films then expected based on EHL (Elasto-Hydrodynamic Lubrication) theory.

Inside the bearing contacts (micro) slip occurs and heat will be generated. In the case of oil lubrication, the oil will act as a coolant for the bearing, reducing the temperature rise and therefore maintaining a sufficiently high viscosity and film thickness. Unfortunately, this is not possible in grease lubrication. There is generally no flow here and therefore no cooling effect by the lubricant.

High temperatures, mechanical work and the build-up of contaminants cause aging of the lubricant. In the case of oil lubrication this will be small due to the cooling and replenishment action. Unfortunately the effect of aging cannot be neglected in grease lubrication. Aging will primarily occur through oxidation of the base oil and thickener and through the breakdown of the structure. A long service life therefore often requires periodic replenishment through active relubrication (systems). Sometimes, the specific rheological behaviour of grease creates difficulties in centralized lubrication systems (pumpability).

Despite the above mentioned drawbacks, there are also clear advantages in using grease as a lubricant. Generally, friction levels are lower than in the case of oil lubrication, primarily due to the absence of churning, apart from the start-up phase. The next advantage is the ease of operation. Sealed and greased-for-life bearings do not require oil baths, which may leak. A well designed bearing with good quality grease requires no maintenance. In addition, the grease will fulfil a sealing function and form a barrier against entry of contaminants onto the raceway, extending the service life of the bearing.

For the selection of oil, the main parameters are: viscosity, boundary lubrication properties (lubricity) and type of additives. In the selection of grease the properties of the thickener dominate, but again the oil base stock properties are important. The main parameters are: consistency, operating temperature range, oil bleeding properties, viscosity of the base oil, corrosion inhibiting properties (additives) and load carrying capacity. This makes grease selection much more complex than oil selection. In this book the various aspects of grease lubrication in rolling bearings will be described, that is the lubrication of the bearing, the lubrication of the seal, lubrication systems, condition monitoring techniques and test methods. In the next chapter (Chapter 2) the lubrication mechanisms will be described. This chapter will touch upon many items that will be described in the following chapters, such as ‘film thickness’ (Chapters 9 and 10), ‘rheology’ (Chapter 5), ‘flow’ (Chapter 6), ‘oil bleeding’ (Chapter 7), ‘aging’ (Chapter 8) and ‘dynamic behaviour’ (Chapter 11). A large chapter in this book is dedicated to grease composition and properties for the various grease types (Chapter 3). A very important topic is bearing service life, which is given by the life of the grease (Chapter 4) and the life of the bearing (Chapter 13) supported by a separate chapter on reliability (Chapter 12).

Finally, separate chapters are dedicated to seal lubrication (Chapter 14), condition moni-toring (Chapter 15), test methods (Chapter 16) and lubrication systems (Chapter 17).

1Lard was used for the lubrication of traditional windmills in the Netherlands.

![]()

2

Lubrication Mechanisms

2.1 Introduction

Compared to oil lubrication, the physics and chemistry of lubricating grease in a rolling bearing is today not well understood. Howevere, it is certain that grease provides the bearing with a lubricating film that is initially thick enough to (at least partly) separate the rolling elements from the raceways. Unfortunately, generally the thickness and/or the ‘lubricity’ of this film changes over time, leading to a limited period in which the grease is able to lubricate the bearing, generally denoted as ‘grease life’. This time is preferably much longer than the fatigue life of the bearing. It is still not fully understood how this film is generated or how it deteriorates over time and leads to bearing damage and ultimately failure.

Although an exact prediction of the film thickness and ‘lubricity’ cannot be made, it is certain that a number of aspects are very important in the prediction of the performance of the grease and/or in selecting the optimum grease for the specific bearing application. Examples are the rheology (flow properties of the grease), the bleeding characteristics, EHL oil film formation, boundary film formation, starvation, track replenishment, thermal aging (such as oxidation) and mechanical aging [374].

Another important aspect in grease lubrication in rolling bearings is that the ‘grease life’ is not deterministic, that is, there is no absolute value for this and it is given by a statistical distribution. Even if bearings are running under very well controlled conditions, such as in a laboratory situation, there is the usual significant spread of failures. The ‘grease’ life is therefore usually defined as L10, that is, the time at which 10% of a population of bearings is expected to have failed [280], similar to bearing life. If a higher reliability is required, a correction is needed. To prevent grease failures, a bearing may be relubricated. If possible, this should be done well before failure is to be expected. Generally, the relubrication interval is defined as L01, that is the time at which 1% of a population of bearings is expected to have failed [280].

All this, and more, will be treated in this book in separate chapters. To give the reader a summary and an introduction to these chapters, the possible mechanisms in combination with the physical aspects of grease lubrication will first be given in this chapter.

2.2 Definition of Grease

Grease is defined as ‘a solid to semi-fluid product or dispersion of a thickening agent in a liquid lubricant. Other ingredients imparting special properties may also be included’ [450]. The base oil is kept inside the thickener structure by a combination of Van der Waals and capillary forces [70]. Interactions between thickener molecules are dipole-dipole including hydrogen bonding [282] or ionic and Van der Waals forces [197]. The effectiveness of these forces depends on how these fibres contact each other. The thickener fibres vary in length from about 1–100 microns and have a length diameter ratio of 10–100, where this ratio has been correlated with the consistency of the grease for a given concentration of thickener [518]. Sometimes grease is called a thickened oil (rather than a thick oil) [226, 230]. Generally, a lubricating grease shows visco-elastic semi-plastic flow behaviour giving it a consistency such that it does not easily leak out of the bearing.

2.3 Operating Conditions

The lubrication process is different for different speeds and temperatures and even for different bearing types. At high temperatures, oxidation and loss of consistency play a major role. At very low temperatures, the high values for consistency and/or viscosity may lead to too high start-up friction torque. The temperature window at which a grease can...