![]()

Chapter 1

Corrosion and Its Definition

According to American Society for Testing and Materials’ corrosion glossary, corrosion is defined as “the chemical or electrochemical reaction between a material, usually a metal, and its environment that produces a deterioration of the material and its properties”.1

Other definitions include Fontana’s description that corrosion is the extractive metallurgy in reverse,2 which is expected since metals thermodynamically are less stable in their elemental forms than in their compound forms as ores. Fontana states that it is not possible to reverse fundamental laws of thermodynamics to avoid corrosion process; however, he also states that much can be done to reduce its rate to acceptable levels as long as it is done in an environmentally safe and cost-effective manner.

In today’s world, a stronger demand for corrosion knowledge arises due to several reasons. Among them, the application of new materials requires extensive information concerning corrosion behavior of these particular materials. Also the corrosivity of water and atmosphere have increased due to pollution and acidification caused by industrial production. The trend in technology to produce stronger materials with decreasing size makes it relatively more expensive to add a corrosion allowance to thickness. Particularly in applications where accurate dimensions are required, widespread use of welding due to developing construction sector has increased the number of corrosion problems.3 Developments in other sectors such as offshore oil and gas extraction, nuclear power production and medicinal health have also required stricter rules and control. More specifically, reduced allowance of chromate-based corrosion inhibitors due to their toxicity constitutes one of the major motivations to replace chromate inhibitors with environmentally benign and efficient ones.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Corrosion Process and Affecting Factors

There are four basic requirements for corrosion to occur. Among them is the anode, where dissolution of metal occurs, generating metal ions and electrons. These electrons generated at the anode travel to the cathode via an electronic path through the metal, and eventually they are used up at the cathode for the reduction of positively charged ions. These positively charged ions move from the anode to the cathode by an ionic current path. Thus, the current flows from the anode to the cathode by an ionic current path and from the cathode to the anode by an electronic path, thereby completing the associated electrical circuit. Anode and cathode reactions occur simultaneously and at the same rate for this electrical circuit to function.4 The rate of anode and cathode reactions (that is the corrosion rate), is defined by American Society for Testing and Materials as material loss per area unit and time unit.1

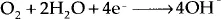

In addition to the four essentials for corrosion to occur, there are secondary factors affecting the outcome of the corrosion reaction. Among them there are temperature, pH, associated fluid dynamics, concentrations of dissolved oxygen and dissolved salt. Based on pH of the media, for instance, several different cathodic reactions are possible. The most common ones are:

Hydrogen evolution in acid solutions,

Oxygen reduction in acid solutions,

Hydrogen evolution in neutral or basic solutions,

Oxygen reduction in neutral or basic solutions,

The metal oxidation is also a complex process and includes hydration of resulted metal cations among other subsequent reactions.

In terms of pH conditions, this book has emphasized near neutral conditions as the media leading to less emphasis on hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions, since both hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions that take place in acidic conditions are less common.

Among cathode reactions in neutral or basic solutions, oxygen reduction is the primary cathodic reaction due to the difference in electrode potentials. Thus, oxygen supply to the system, in which corrosion takes place, is of utmost importance for the outcome of corrosion reaction. Inhibitors are commonly tested in stagnant solutions for the purpose of weight-loss tests, thus ruling out the effects of varying fluid dynamics on corrosion. Weight-loss tests are performed at ambient conditions, thus effects of temperature and dissolved oxygen amounts are not tested as well, while for salt fog chamber tests, temperature is. varied for accelerated corrosion testing. For both weight loss tests and salt fog chamber tests, however, dissolved salt concentrations are commonly kept high for accelerated testing to be possible.

When corrosion products such as hydroxides are deposited on a metal surface, a reduction in oxygen supply occurs, since the oxygen has to diffuse through deposits. Since the rate of metal dissolution is equal to the rate of oxygen reduction, a limited supply and limited reduction rate of oxygen will also reduce the corrosion rate. In this case the corrosion is said to be under cathodic control.5 In other cases corrosion products form a dense and continuous surface film of oxide closely related to the crystalline structure of metal. Films of this type prevent primarily the conduction of metal ions from metal-oxide interface to the oxide-liquid interface, resulting in a corrosion reaction that is under anodic control.5 When this happens, passivation occurs and metal is referred as a passivated metal. Passivation is typical for stainless steels and aluminum.

![]()

Chapter 3

Corrosion Types Based on Mechanism

Brief definitions of major types of corrosion will be given in this section in the order of commonalities and importance of these corrosion types for the metal alloys, which are mild steel, and Aluminum 2024, 6061 and 7075 alloys.

3.1 Uniform Corrosion

Uniform corrosion occurs when corrosion is quite evenly distributed over the surface, leading to a relatively uniform thickness reduction.6–7 Metals without significant passivation tendencies in the actual environment, such as iron, are liable to this form. Uniform corrosion is assumed to be the most common form of corrosion and responsible for most of the material loss.6 However, it is not a dangerous form of corrosion because prediction of thickness reduction rate can be done by means of simple tests.7 Therefore, corresponding corrosion allowance can be added, taking into account strength requirements and lifetime.

3.2 Pitting Corrosion

Pitting corrosion is one of the most observed corrosion types for aluminum and steel, and it is the most troublesome one in near neutral pH conditions with corrosive anions, such as Cl−or SO42- present in the media.8–11 It is characterized by narrow pits with a radius of equal or lesser magnitude than the depth. Pitting is initiated by adsorption of aggressive anions, such as halides and sulfates, which penetrate through the passive film at irregularities in the oxide structure to the metal-oxide interface. It is not clear why the breakdown event occurs locally.9 In the highly disordered structure of a metal surface, aggressive anions enhance dissolution of the passivating oxide. Also, adsorption of halide ions causes a strong increase of ion conductivity in the oxide film so that the metal ions from the metal surface can migrate through the film.

Thus, locally high concentrations of aggressive anions along with low solution pH values strongly favor the process of pitting initiation. In time, local thinning of the passive layer leads to its complete breakdown, which results in the formation of a pit. Pits can grow from a few nanometers to the micrometer range. In the propagation stage, metal cations from the dissolution reaction diffuse toward the mouth of the pit or crevice (in the case of crevice corrosion), where they react with OH− ions produced by the cathodic reaction, forming metal hydroxide deposits that may cover the pit to a varying extent. Corrosion products covering the pits facilitate faster corrosion because they prevent exchange of the interior and the exterior electrolytes, leading to very acidic and aggressive conditions in the pit.9–11 Stainless steels have high resistance to initiation of pitting. Therefore, rather few pits are formed, but when a pit has been formed, it may grow very fast due to large cathodic areas and a thin oxide film that has considerable electrical conductance.12 Conversely for several aluminum alloys, pit initiation can be accepted under many circumstances. This is so because numerous pits are formed, and the oxide is insulating and has, therefore, low cathodic activity. Thus, corrosion rate is under cathodic control. However, if the cathodic reaction can occur on a different metal because of galvanic connection as for deposition of Cu on the aluminum surface, pitting rate may be very high. Therefore, the nature of alloying elements is very important.13

3.3 Crevice Corrosion

Crevice corrosion occurs underneath deposits and in narrow crevices that obstruct oxygen supply.14–16 This oxygen is initially required for the formation of the passive film and later for repassivation and repair. Crevice corrosion is a localized corrosion concentrated in crevices in which the gap is wide enough for liquid to penetrate into the crevice but too narrow for the liquid to flow. A special form of crevice corrosion that occurs on steel and aluminum beneath a protecting film of metal or phosphate, such as in cans exposed to atmosphere, is called filiform corrosion.14 Provided that crev...