![]()

Chapter 1

Context

This chapter describes the general context in which this work has been conducted, how our work takes its roots and how this research can be placed in the field of electronic design.

In section 1.1 of this chapter, we highlight the importance nowadays of embedded systems. Section 1.2 stresses the relationship between memory management and three relevant cost metrics (such as power consumption, area and performance) in embedded systems. This explains the considerable amount of research carried out in the field of memory management. Then, the following section presents a brief survey of the state of the art in optimization techniques for memory management, and, at the same time, positions our work with respect to the aforementioned techniques. Finally, operations research for electronic design is taken into consideration for examining the mutual benefits of both disciplines and the main challenges exploiting operations research methods to electronic problems.

1.1. Embedded systems

There are many definitions for embedded systems in the literature (for instance [HEA 03], [BAR 06], [KAM 08] and [NOE 05]) but they all converge toward the same point: “An embedded system is a minicomputer (microprocessor-based) system designed to control one specific function or a range of functions; but, it is not designed to be programmed by the end user in the same way that a personal computer (PC) is”.

A PC is built to be flexible and to meet a wide range of end user needs. Thus, the user can change the functionality of the system by adding or replacing software, for example one minute the PC is a video game platform and the next minute it can be used as a video player. In contrast, the embedded system was originally designed so that the end user could make choices regarding the different application options, but could not change the functionality of the system by adding software. However, nowadays, this distinction is less and less relevant; for example it is more frequent to find smartphones where we can change their functionality by installing appropriate software. In this manner, the breach between a PC and an embedded system is shorter today than it was in the past.

An embedded system can be a complete electronic device or a part of an application or component within a larger system. This explains its wide range of applicability. Embedded systems range from portable devices such as digital watches to large stationary installations such as systems controlling nuclear power plants.

Indeed, depending on application, an embedded system can monitor temperature, time, pressure, light, sound, movement or button sensitivity (like on Apple iPods).

We can find embedded systems helping us in every day common tasks; for example alarm clocks, smartphones, security alarms, TV remote controls, MP3 players and traffic lights. Not to mention modern cars and trucks that contain many embedded systems: one embedded system controls the antilock brakes, another monitors and controls the vehicle’s emissions and a third displays information in the dashboard [BAR 06].

Besides, embedded systems are present on real-time systems. The main characteristic of these kinds of systems is timing constraints. A real-time system must be able to make some calculations or decisions in a timely manner knowing that these important calculations or activities have deadlines for completion [BAR 06]. Real-time systems can be found in telecommunications, factory controllers, flight control and electronic engines. Not forgetting, the real-time multi-dimensional signal processing (RMSP) domain that includes applications, like video and image processing, medical imaging, artificial vision, real-time 3D rendering, advanced audio and speech coding recognition [CAT 98b].

Contemporary society, or industrial civilization, is strongly dependent on embedded systems. They are around us simplifying our tasks and pretending to make our life more comfortable.

1.1.1. Main components of embedded systems

Generally, an embedded system is mainly composed of a processor, a memory, peripherals and software. Below, we give a brief explanation of these components.

– Processor: this should provide the processing power needed to perform the tasks within the system. This main criterion for the processor seems obvious but it frequently occurs that the tasks are either underestimated in terms of their size and/or complexity or that creeping elegance1 expands the specification beyond the processor’s capability [HEA 03].

– Memory: this depends on how the software is designed, written and developed. Memory is an important part of any embedded system design and has two essential functions: it provides storage for the software that will be run, and it provides storage for data, such as program variables, intermediate results, status information and any other data created when the application runs [HEA 03].

– Peripherals: these allow an embedded system to communicate with the outside world. Sensors that measure the external environment are typical examples of input peripherals [HEA 03].

– Software: this defines what an embedded system does and how well it does it. For example, an embedded application can interpret information from external sensors by adopting algorithms for modeling external environments. Software encompasses the technology that adds value to the system.

In this work, we are interested in the management of embedded system memory. Consequently, the other embedded system components are not addressed here. The next section justifies this choice.

1.2. Memory management for decreasing power consumption, performance and area in embedded systems

Embedded systems are very cost sensitive and in practice, the system designers implement their applications on the basis of “cost” measures, such as the number of components, performance, pin count, power consumption and the area of the custom components. In previous years, the main focus has been on area-efficient designs. In fact, most research in digital electronics has focused on increasing the speed and integration of digital systems on a chip while keeping the silicon area as small as possible. As a result, the design technology is powerful but power hungry. While focusing on speed and area, power consumption has long been ignored [CAT 98b].

However, this situation has changed during the last decade mainly due to the increasing demand for handheld devices in the areas of communication (e.g. smartphones), computation (e.g. personal digital assistants) and consumer electronics (e.g. multimedia terminals and digital video cameras). All these portable systems require sophisticated and power-hungry algorithms for high-bandwidth wireless communication, video-compression and -decompression, handwriting recognition, speech processing and so on. Portable systems without low-power design suffer from either a very short battery life or an unreasonably heavy battery. This higher power consumption also means more costly packaging, cooling equipment and lower reliability. The latter is a major problem for many high-performance applications; thus, power-efficient design is a crucial point in the design of a broad class of applications [RAB 02, CAT 98b].

Lower power design requires optimizations at all levels of the design hierarchy, for example technology, device, circuit, logic, architecture, algorithm and system level [CHA 95, RAB 02].

Memory design for multi-processor and embedded systems has always been a crucial issue because system-level performance strongly depends on memory organization. Embedded systems are often designed under stringent energy consumption budgets to limit heat generation and battery size. Because memory systems consume a significant amount of energy to store and to forward data, it is then imperative to balance (trade-off) energy consumption and performance in memory design [MAC 05].

The RMSP domain and the network component domain are typical examples of data-dominated applications2. For data-dominated applications, a very large part of the power consumption is due to data storage and data transfer. Indeed, a lot of memory is needed to store the data processed; and huge amounts of data are transfered back and forth between the memories and data paths3. Also, the area cost is heavily impacted by memory organization [CAT 98b].

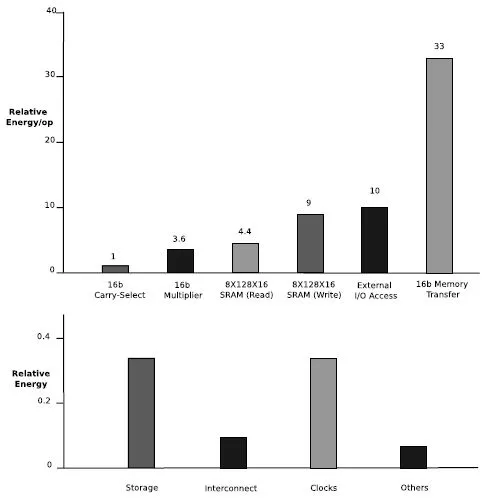

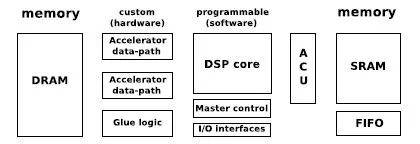

Figure 1.1, taken from [CAT 98b], shows that data transfers and memory access operations consume much more power than a data-path operation in both cases: hardware and software implementations. In the context of a typical heterogeneous system architecture, which is illustrated in Figure 1.2 (taken from [CAT 98b]), this architecture disposes of custom hardware, programmable software and a distributed memory organization that is frequently costly in terms of power and area. We can estimate that downloading an operand from off-chip memory for a multiplication consumes approximately 33 times more power than the multiplication itself for the hardware processor. Hence, in the case of a multiplication with two factors where the result is stored in the off-chip memory, the power consumption of transferring data is approximately 100 times more than the actual computation.

Figure 1.1. Dominance of transfer and storage over data-path operation both in Hardware and Software

Furthermore, studies presented in [CAT 94], [MEN 95], [NAC 96], [TIW 94] and [GON 96] confirm that data transfer and storage dominates power consumption for data-dominated applications in hardware and software implementations.

In the context of memory organization design, there are two strategies for minimizing the power consumption in embedded systems. The first strategy is to reduce the energy consumed in accessing memories. This takes a dominant proportion of the energy budget of an embedded system for data-dominated applications. The second strategy is to minimize the amount of energy consumed when information is exchanged between the processor and the memory. It reduces the amount of required processor-to-memory communication bandwidth [MAC 05].

Figure 1.2. Typical heterogeneous embedded architecture

1.3. State of the art in optimization techniques for memory management and data assignment

It is clear that memory management has an impact on important cost metrics: area, performance and power consumption. In fact, the processor cores begin to push the limits of high performance, and the gap between processor and memory widens and usually becomes the bottleneck in achieving high performance. Hence, the designers of embedded systems have to carefully pay attention to minimize memory requirements, improve memory throughput and limit the power consumption by the system’s memory. Thus, the designer attempts to minimize memory requirements with the aim of lowering overall system costs.

We distinguish three problems concerning memory management and data assignment. The first problem is software oriented and aims at optimizing application code source regardless of the architecture; it is called a software optimization and it is presented in section 1.3.1. In the second problem, the electronic designer searches for the best architecture in terms of cost metrics for a specific embedded application. This problem is described in section 1.3.2. In the third problem, the designer is concerned with binding the application data into memory in a fixed architecture so as to minimize power consumption. This problem is presented in section 1.3.3.

1.3.1. Software optimization

We present some global optimizations that are independent of the target architectural platform; readers interested in more details about this are refereed to [PAN 01b]. These optimization techniques take the form of source-to-source code transformations. This has a positive effect on the area consumption by reducing the amount of data transfers and/or the amount of data to be stored. Software optimization often improves performances cost and power consumption, but not always. They are important in finding the best alternatives in higher levels of the embedded system design.

Code-rewriting techniques consist of loop and data-flow transformations with the aim of reducing the required amount of data transfer and storage, and improving access behavior [CAT 01]. The goal of global data-flow transformation is to reduce the number of bottlenecks in the algorithm and remove access redundancy in the data flow. This consists of avoiding unnecessary copies of data, modifying computation order, shifting of “delay lines” through the algorithm to reduce the storage requirements and recomputing issues to reduce the number of transfers and storage size [CAT 98a]. Basically, global loop and control-flow transformations increase the locality and regularity of the code’s accesses. This is clearly good for memory size (area) and memory accesses (power) [FRA 94] but of course also for performance [MAS 99]. In addition, global loop and control-flow transformations reduce the global life-times of the variables. This removes system-level copy overhead in buffers and enables storing data in smaller memories closer to the data paths [DEG 95, KOL 94].

The hierarchical memory organization is a memory optimization technique (see [BEN 00c] for a list of references). It reduces memory energy by exploiting the non-uniformities in access frequencies to instructions and data [HEN 07]. This technique consists of placing frequently accessed data into small energy-efficient memories, while rarely accessed information is stored in large memories with high cost per access. The energy cost of accessing and communicating with the small memories is much smaller than the cost required to fetch and store information in large memories [BEN 00a, CUP 98].

A good way for decreasing the memory traffic, as well as memory energy, is to compress the information transmitted between two levels of memory hierarchy [MAC 05]. This technique consists of choosing the set of data elements to be compressed/decompressed and the time instants during execution at which these compressions or decompressions should be performed [OZT 09]. The memory bottlenecks are mainly due to the increasing code complexity of embedded applications and the exponential increase in the amount of data to manipulate. Hence, reducing the memory-space occupancy of embedded applications is very important. For this reason, designers and researchers have devised techniques for improving the code density (code compression), in terms of speed, area and energy [BAJ 97]. Data compression techniques have been introduced in [BEN 02a, BEN 02b].

Ordering and bandwidth optimization guarantees that the real-time constraints are presented with a minimal memory bandwidth-related costs. Also, this determines which data should be made simultaneously accessible in the memory architecture.

Moreover, storage-bandwidth optimization takes into account the effect on power dissipation. The data that are dominant in terms of power consumption are split into smaller pieces of data. Indeed, allocating more and smaller memories usually results in less power consumption; but the use of this technique is limited by the additional costs generated by routing overheads, extra design effort and more extensive testing in the design [SLO 97].

This chapter does not cover optimization techniques on source code transformation. It is focused on optimization techniques on hardware and on data binding in an existing memory architecture.

1.3.2. Hardware optimization

We now present some techniques for optimizing the memory architecture design of embedded systems.

The goal of memory allocation and data assignment is to determine an optimal memory architecture for data structures of a specific application. This decides the memory parameters, such as the number and the capacity of memories and the number of ports in each memory. Different choices can lead to solutions with a very different cost, which emphasize how important these choices are. The freedom of the memory architecture is constrained by the requirements of the application. Allocating more or less memories has an effect on the chip area and on the energy consumption of the memory architecture. Large memories consume more energy per access than small memories, because of longer word – and bit – lines. So the energy consumed by a single large memory containing all the data is much larger than when the data are distributed over several smaller memories. Moreover, the area of a single memory solution is often higher when different arrays have different bit widths [PAN 01b].

For convenience and with the aim of producing sophisticated solutions, memory allocation and assignment is subdivided into two subproblems (a systematic technique has been published for the two subproblems in [SLO 97], [CAT 98c] and [LIP 93]). The first subproblem consists of fixing the number of memories and the type of each of them. The term “type” includes the number of access ports of the memory, whether it is an on-chip or an off-chip memory. The second subproblem decides in which of the allocated memories each of the application’s array (data) will be stored. Hence, the dimensions of the memories are determined by the characteristics of the data assigned to each memory and it is possible to estimate the memory cost. The cost of memory architecture depends on the word-length (bits) and the number of words of each memory, and the number of times each of the memories is accessed. Using this cost estimation, it is possible to explore different alternative assignment schemes and select the best one for implementation [CAT 98b]. The search space can be explored using either a greedy constructive heuristic or a full-search branch and bound approach [CAT 98b]. For small applications, branch and bound method and integer linear programming (ILP) find optimal solutions, but if the size of the application gets larger, these algorithms take a huge computation time to generate an optimal solution.

For one-port (write/read) memories, memory allocation and assignment problems can be modeled as a vertex coloring problem [GAR 79]. In this conflict graph, a variable is represented by a vertex, a memory is represented by a color and an edge is present between two conflicting variables. Thus, the variable of the application is “colored” with the memories to which they are assigned. Two variables in conflict cannot have the same color [CAT 98b]. This model is also used for assigning scalars to registers. With multi port memories, the conflict graph has to be extended with loops and hyperedges and an ordinary coloring is not valid anymore.

The objective of in-place mapping optimization is to find the optimal placement of the data inside the memories such that the required memory capacity is minimal [DEG 97, VER 91]. The goal of this strategy is to reuse memory location as much as possible and hence reduce the storage size requirements. This means that several data entities can be stored at the same location at different times. There are two subproblems: the intra-array storage and inter-array storage [CAT 98b]. The intra-array storage refers to the internal organization of an array in memory [LUI 07b, TRO 02]. The inter-array storage refers to the relative position of different arrays in memory [LUI 07a]. Balasa et al. [BAL 08] give a tutorial overview on the existing techniques for the evaluation of the data memory size.

A data transfer and storage exploration methodology is a technique for simultaneous optimization of memory architecture and access patterns. It has also been proposed for the case of data-dominated applications (e.g.multimedia devices) and network component applications (e.g. Automated Teller Machine applications) [CAT 98b, BRO 00, CAT 94, CAT 98a, WUY 96]. The goal of this methodology is to determine an optimal execution order for the dat...