![]()

CHAPTER 1

Tulip Madness

In popular culture, there is probably no better-known event in the lexicon of unusual financial history than the tulipmania that seized Holland in the early seventeenth century. Whenever there is a financial bubble in modern times, the term tulipmania is bandied about, but few commentators who use the term have a grasp as to what actual events occurred.

It is a fascinating tale—perhaps somewhat apocryphal—and, if nothing else, entertaining. And it is surely the only chapter in this compendium of financial history that involves not one but two important biological maladies that shaped the story: a flower-distorting virus and a deadly human plague.

■ An Introduction to the Flower in Question

If you’ve ever grown tulips, you know all too well that, while beautiful, the tulip is a temperamental and relatively weak plant whose bloom is short-lived and whose likelihood of returning the next year is far from certain.

The flower itself was unknown to most of Europe in the sixteenth century, but around 1554, the Pope’s ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey was charmed by the flower and collected seeds and bulbs for distribution. (The word tulip itself is said to be derived from the Turkish word for “turban,” since the bloom somewhat resembles the same).

Cultivation spread throughout the region we today call the Netherlands as tulip bulbs found their way to Vienna, Antwerp, and Amsterdam. Planters took pleasure in the vibrant blooms and the fact that the plants were more tolerant of the harsher climate of the lower countries.

The bulbs themselves were classified into three groups: the single-colored, the multicolored, and the “bizarres.” This last category is most germane to the tale of tulipmania, as bizarres were the rarest and most sought-after tulip. The reason these unusual flowers came about was a virus that interfered with the plant’s ability to create a uniform color on the petal. It is today known as a “breaking” virus, since it breaks the plant’s lock on a single petal color, although it does not kill the plant itself. The effect on the flower was striking, producing mosaic-like flames of color on each petal.

Even regular, single-colored tulips are difficult to grow from seeds. It took anywhere from 7 to 12 years to produce a flowering bulb from a seed, and once the bulb was at long last established, it would create only one or two clones (or “offsets”) in a given year. The mother bulb itself would last only a few years before it died.

As challenging as it was to propagate regular tulips, it was even harder to do so for the exotic varieties, since the virus weakened the plant somewhat, and it usually failed to create offsets, meaning that any bizarre varieties required new plants be created from seeds. The length of time required for that growth meant that the most appealing varieties of tulips remained rare.

As knowledge of tulips spread, collectors of the bulbs began to give the exotic varieties inventive names such as “Admiral” and “General” to suggest the boldness of the plant’s appearance. A sort of one-upmanship developed with the naming, leading to exalted titles like “Admiral of Admirals” and “General of Generals.” For years, the cultivation and selling of tulip bulbs was little more than a curious hobby among horticulturists and the well-to-do.

■ Rise of the Tulip

As the sixteenth century turned over to the seventeenth, Holland was on the ascent. The area, formerly known as the Spanish Netherlands, had won its independence. Amsterdam, the capital of Holland, found itself as the driving force behind commerce, particularly as a trading partner with the East Indies. Newfound wealth and prosperity flooded the region, with single trading voyages yielding profits upwards of 400 percent to the financiers backing them.

A merchant class arose, and the new money in the area sought ways to show off its wealth. Grand estates begin springing up around Amsterdam, and nothing framed a handsome home better than a vibrant display of flowers in the surrounding gardens. And, naturally, there were precious few flowers more showy and eye-catching than the tulip.

The tulip’s reputation was on the rise, and by 1634, anyone with money but without tulips was judged simply to have bad taste. Whereas tulip bulbs used to be sold by the pound, their rising popularity and prices made them exponentially more precious, and soon much tinier weights were used as the basis of the tulip trade. A concurrent demand from French speculators for the bulbs only pushed the price higher.

The trading of the bulbs was framed by the growing season of the flowers themselves. Tulips bloom in the springtime for just a few weeks, and they enter a dormant phase from June through September. It is at this time they can be safely uprooted and moved about, so actual physical trades took place around this time of the year.

Because speculators did not want to confine their trading to just a few months, they put together what could be considered a futures market. Two traders could sign a contract in front of a notary, pledging to buy a certain quantity, type, and quality of bulb at the end of the season for a certain price. These contracts soon found an aftermarket of their own, so that people begin trading the paper instead of the physical bulbs.

■ Market Frenzy

In 1636, the tulip bulb was the fourth leading export of Holland (if you are curious, the leading three were gin, herring, and cheese). Because the margin requirements for tulip futures were minimal, the price of the contracts began to soar spectacularly. Some historians have noted that, due to the presence of the bubonic plague at the time, some individuals viewed life quite fatalistically, leading some speculators to trade with complete imprudence.

The Calvinists of Amsterdam viewed with dismay and concern the speculative frenzy that was springing up in their native land. The virtues of discretion, moderation, and hard work seemed to be shoved aside for the easy profits of trading in paper. The appeal of the profits at the time was understandable, however, as prices lurched forward. By 1637, a single bulb could fetch the equivalent of 10 years’ salary of a skilled craftsman. Entire estates—one reported to be a full 12 acres—could be had for a single exotic “bizarre” bulb.

One of these bulbs, named the Semper Augustus (see Figure 1.1), was particularly coveted. In 1636, there were only two such bulbs in all of Holland. As trading spread throughout the country, it became impractical for speculators to make the trip to Amsterdam, so smaller exchanges appeared in the taverns of small towns using similar trading rules as had been established in the capital city. To create an atmosphere of prosperity and opulence, these taverns were often adorned with large vases of tulips in full bloom and sumptuous dinners that traders could enjoy while doing their business.

The final spasm of buying was promulgated by a decision made in February 1637 by the self-regulating guild of Dutch florists. They agreed that, by their new rules, all the futures contracts that had been put in place since November 30, 1636, could henceforth be considered options contracts. This wasn’t the exact language they used, of course, since such terms for financial instruments did not exist, but the effect was the same.

The difference between a futures contract and an options contract is subtle but crucial: with a futures contract, the buyer agreed to buy a certain quantity of a product at a certain price on a certain date; the obligation to buy was firm. With an options contract, the buyer had the right—but not the obligation—to execute a purchase based on the same terms.

To cite an example, if a person bought an option contract when the underlying asset had a value of 500, and the asset’s value went to 800 by the expiration date of the contract, the buyer would presumably be glad to honor the terms of the agreement and purchase the product at 500 (since the market price was already up 60 percent). However, if the price had dropped to 250, the buyer could simply let the contract expire, losing only a small transaction fee equivalent to about 3.5 percent of the contract price.

With this new rule proposed, which the Dutch Parliament ratified, the risk of engaging in these contracts to the buyers decreased dramatically (indeed, by 96.5 percent). The reason is that those trading in tulip futures now bore very little risk, since they could simply walk away from the agreement if prices didn’t behave favorably. If tulips ascended in price, the speculators made a lot of money. If the tulips fell in price, speculators lost only a small amount of risk capital.

It was at this time that trading reached its peak, in terms of both price and volume. Some bulb agreements changed hands 10 times in a single day.

The market finally broke down during a routine bulb auction held in Haarlem, Holland. A mass of sellers showed up to conduct business, but there wasn’t a single buyer to be found. Some believe a severe outbreak of the bubonic plague kept the buyers away (although it seems to have done nothing to deter the sellers), but the simple fact is that the normal spot market for bulbs was suddenly one-sided and thus nonexistent. All sellers and no buyers does not a market make.

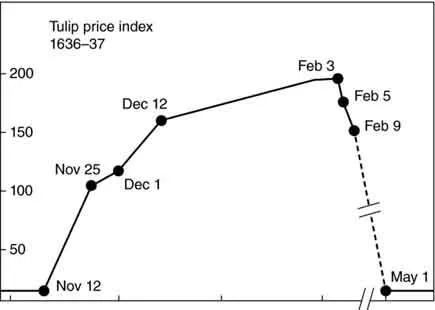

Within days, panic spread across the country, as people soon realized that their enormous trading profits were no more valuable than the paper on which the agreements were written (see Figure 1.2).

■ The Bloom Is off the Rose

The crash in tulip prices was even more rapid than the ascent. One bulb that had risen in price 26-fold by January 1637 lost 95 percent of its value in just one week. Speculators around the nation were facing losses that were in some cases ruinous.

Citizens demanded that their government do something about it, so the matter was referred to the Provincial Council of The Hague. After three months of discussion and debate, the Council made their announcement, which was this: they had no decision, and they would need more information. Not surprisingly, this provided cold comfort to the distressed populace.

The Council’s follow-up suggestion wasn’t much more helpful: they advised that every seller should meet with each corresponding buyer and, in front of witnesses, offer the tulips to the purchaser for the previously agreed price. If the buyer refused to complete the deal, the tulips could be put up for sale in a public auction, and the buyer would be held responsible for...