- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This collection of high-profile contributions provides a unique insight into the development of novel, successful biopharmaceuticals.

Outstanding authors, including Nobel laureate Robert Huber as well as prominent company researchers and CEOs, present valuable insider knowledge, limiting their scope to those procedures and developments with proven potential for the biotechnology industry. They cover all relevant aspects, from the establishment of biotechnology parks, the development of successful compounds and the implementation of efficient manufacturing processes, right up to the establishment of advanced delivery routes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Modern Biopharmaceuticals by Jörg Knäblein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biotechnology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Modern Biopharmaceuticals: Research is the Best Medicine – Sanitas Summum Bonus

“In all things of nature there is something of the marvelous.”

Aristotle (384–322 BC)

1

Twenty Thousand Years of Biotech – From “Traditional” to “Modern Biotechnology”

1.1 Biotechnology – The Science Creating Life

“Biotechnology” is a combination of the Greek words bios, techne, and logos, meaning life, technology, and knowledge. Hence, biotechnology is the technical application of existing knowledge on bacteria for the weal of humankind. Or, according to a less-impassioned definition from the University of Hohenheim: “...technical (fermentation) processes applying organisms, cells or parts thereof with the aim to manufacture products for the pharmaceutical, food or cosmetics industry as well as sustainable waste reduction in the environmental biotechnology field.”

Even more complex is the 1989 European Federation of Biotechnology (EFB) definition: “...the integrated application of natural and engineering sciences in order to technically use organisms, cells, parts thereof and their molecular analogous. Thus, biotechnology deals with the application of biological processes for technical and industrial production and hence is a very application-oriented science of microbiology and biochemistry in tight conjunction with technical chemistry and process engineering.”

As we can see, although definitions of the term “biotechnology” can be somewhat different, one thing they all have in common: biotechnology improves our daily life (e.g., biopharmaceuticals or genetically engineered food) – in some cases biotechnology is the only enabler of life!

1.2 The Inauguration of Biotechnology

Since thousands of years people manipulated nature in order to make the maximum use of it – first biological, then technological, and finally biotechnological (Figure 1.1). Already eighteen thousand years before Christ, people in the Middle East had successfully domesticated sheep and deer – later (about 5000 BC) pigs by the Chinese. At the same time, the Sumerians in Mesopotamia (the area between Euphrates and Tigris, in which according to the Holy Bible “milk and honey was streaming” – today Iraq) were capable of brewing beer as depicted in detail on the Monument Bleu – a Sumerian stone drawing kept in the Paris Louvre – showing the process of wheat preparation for beer production. In some years, almost half of the entire wheat harvest was used for brewing the typical beer (Kasch or Bufa). It should be mentioned though that these early biotechnologies were very empirical and the underlying processes far from being reproducible.

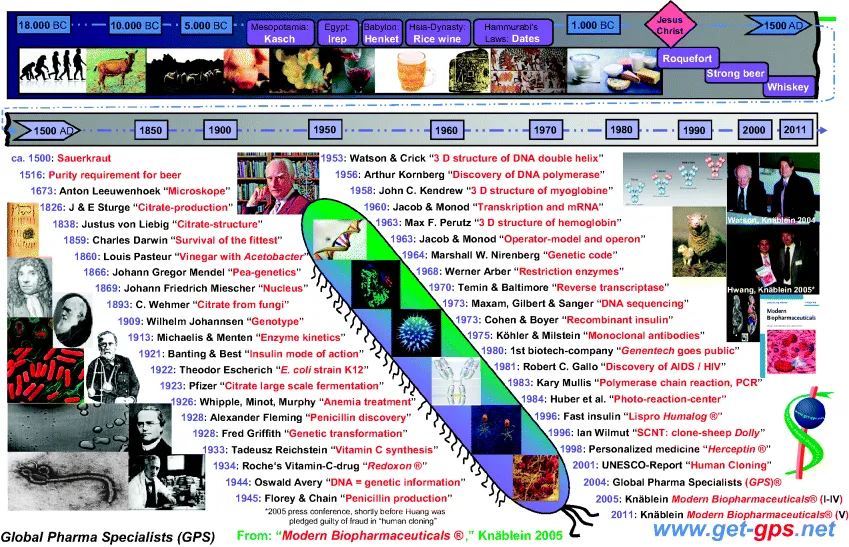

Figure 1.1 Twenty thousand years of biotech: “Traditional Biotechnology” exists since 20 000 years – “Modern Biotechnology” since the advent of genetic engineering.

Another thousand years later, the Egyptians developed the art of winemaking (Irep) almost to perfection, and about 3000 BC, the Babylonians were able to brew 20 different types of beer. In Egypt, in 2600 BC, beer (Henket) was considered a staple food and the breweries were a royal monopoly – the situation was similar in 2200 BC with rice beer during the Chinese Hsia Dynasty. Another biotechnology was mentioned around 1700 BC in the “Laws of Sumerian King Hammurabi” (1728–1686 BC; one of the most influential leaders in the orient): a hand-fertilization technique for date palm trees.

Specific fermentation processes were established in areas in which all required ingredients were available: wheat beer in Middle Europe (malt, hops, Saccharomyces cerevisiae), rice wine (rice, Aspergillus oryceae), rice liquor sake in East Asia (rice, koji, S. cerevisiae), kvass in Russia (wheat malt, rye flour, Lactobacillus spec.), pombe in South America and Central Africa (millet mash and yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe), and pulque by the Aztecs in Middle America (fruits, Zymomonas mobilis). People having cows produced yogurt (Streptococcus lactis), kefir (Lactobacillus kefir), and cheese (e.g., Streptococcus salivarius) – although these products were created more or less randomly by spontaneous fermentation due to the approximately 500 000 microbes that naturally occur in just 1 ml of milk. In contrast, the Sumerians developed specific fermentation processes to selectively produce certain different kinds of cheese. Later (around 250 AD), the “Roquefort” (Penicillium roquefortii) was shipped to Rome as a “Gallic specialty.”

In contrast, brewing of beer was only developed in the sixth century into a stable and reproducible fermentation process when monks became more and more interested in this new type of “liquid bread.” Although during the Lenten season, the monks were prohibited to eat, according to the sentence “liquida non fragunt ieiunum” (“liquids do not infringe the abstinence order”), they were allowed to drink – and thanks to that, we nowadays have very delicious and aromatic strong beers. Today in Germany alone, 100 million hectoliters of beer is brewed annually in compliance with the Bavarian purity law from 1516 using exclusively barley malt, hops, water, and special yeast strains. Worldwide, beer is still the top selling biotech product with a yearly consumption of approximately 1.5 billion hectoliters worth more than €50 billion.

1.3 From “Traditional” to “Modern Biotechnology”

Already at the beginning of the last millennium, “traditional” biotechnologies were developed in order to produce “high value traits”: in 1276, the first whiskey distillery was established in Ireland, and two hundred years later certain fermentation processes were optimized using special microorganisms in order to produce sauerkraut (Leuconostoc mesenteroides) and different yogurt types (e.g., Lactobacillus bulgaricus). With a size of only a couple of micrometers, the microbes are not visible to the naked eyes; in 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) was the first person to watch a microorganism at a ×200 magnification using his self-made microscope. In 1684, he published his first drawings of the observed microbes [1] and as a result became scientific member of the very prestigious London Royal Society – albeit he had never visited a university.

Fantastic discoveries paved the way to modern biotechnology in a fast pace. The foundation of classical genetics was laid by the English scientist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) in his revolutionary theories on the principle of natural selection. On July 1, 1859, Darwin presented his seminal paper on the “Survival of the fittest” [2] on the development of animals to the Royal Linnean Society, which still prides itself as the repository of natural history expertise in Britain.

There was very little reaction in the room, but the real furor did not begin until Darwin published “On the Origin of Species” the following year: “There is a grandeur in this view of life ... that whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved” are the concluding lines of the revolutionary book. Darwin, knowing the reaction he was likely to receive, held back for years from airing and then publishing his theories on the principle of natural selection – and his fears were correct: he was pilloried by the scientific and religious establishment of the time. One famous caricature depicted him with the body of a monkey, so angered were people by the suggestion that they might have descended from the monkeys rather than having been created in the image of God.

His theories are still rejected by some, notably creationists in the United States, and are less than welcome in the Middle East. Even in Britain a poll in 2006 showed that only 48% of the people believed in Darwin's evolutionary theories.

Today, we honor the man for the 150th anniversary of his presentation to the Royal Linnean Society, and we celebrate Darwin's 200th birthday and the 150th anniversary of the publication of “On the Origin of Species.” So, obviously, Darwin is still causing waves after 150 years, and most likely he would have been happy to get a fraction of this enthusiasm during his life time....

In 1860, it was the French scientist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) (founder of microbiology and biotechnology) who was using for the first time “pure isolates” (phenotypically identical strains) of Acetobacter to convert alcohol into vinegar. Some years later, in 1866, it was Johann Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) who showed with his experiments on hybrid peers that some of the phenotypic characteristics can be transferred from one generation to the next [3].

1.3.1 Molecular Genetics and Enzymatic Kinetics

The Swiss pathologist Johann Friedrich Miescher (1811–1887) was the first who stained the “nucleus” of a cell and in 1869 at University Tübingen isolated its “nucleic acid.” Although this was essentially the beginning of molecular genetics only, 40 years later, it was the Danish geneticist Wilhelm Johannsen (1857–1927) who coined in 1909 the term “genotype” with its inheritable characteristics – the “genes.”

Another important milestone toward modern biotechnology was the kinetic description of fermentation processes, that is, the time it took to convert a certain substrate S with a specific enzyme E into the product P. Enzymes can catalyze chemical reactions by factors from 100 million up to 1 trillion (108–1012). Assuming a 1012 enzyme-catalyzed reaction takes 1 second to be completed, without enzyme it would theoretically take 300 000 years! Obviously, most of our metabolic reactions would not be feasible without enzymes – hence these biological catalysts enable our life.

The enzymes' catalytic activity stems from their ability to bring substrates into a favored steric orientation – the so-called enzyme–substrate (ES) complex, which reduces the activation energy required to convert the substrate into the respective product. Since one enzyme can only catalyze the reaction of a restricted number of substrate molecules (because at one point all active sites are occupied – the so-called saturation effect), there is a maximum reaction velocity depending on substrate type and enzyme. Chemical reactions without enzymes obviously do not have such kinetics as it was shown already in 1913 by the Berlin biochemists Leonor Michaelis (1875–1949) and Maud L. Menten (1879–1960). From their kinetic experiments, Michaelis and Menten concluded the existence of an ES complex by measuring the maximum velocity for enzyme-catalyzed reactions [4]. This was the earliest evidence (indirectly though) of this phenomenon and therefore today it is called the “Michaelis–Menten kinetic.”

Applying this knowledge to the fermentation process – by feeding the substrate continuously (rather than batch) to avoid the saturation effect – it was possible to control the reaction and maximize the time–space yield in a bioreactor. In the following sections, we will see some examples showing that this was really imperative – in combination with genetic optimization – to produce the required amounts of vital and lifesaving substances on a large scale.

1.3.2 Penicillin and Other Lifesaving Antibiotics

The immense importance for humankind of such biotechnological developments is illustrated nicely in the first example: Alexander Fleming (1881–1955) was working as a bacteriologist at St. Mary's Hospital in London when in 1928 he discovered a clear zone around a fungus, which was (accidentally) growing on an agar dish with Staphylococcus. Obviously, this fungus produced some agent preventing the bacteria to grow – and since he named it as Penicillium notatum, Fleming called the compound Penicillin. When Fleming published his work in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology [5], he did not realize the huge medical potential of this compound against a variety of hazardous bacteria: streptococci, staphylococci, anthrax, diphtheria, glandular fever, and tetanus. Ten years later, in 1938, the Ukrainian biochemist Ernst Boris Chain (1906–1979) at Oxford University understood the general antibacterial potential of Penicillin.

With the beginning of World War II in 1939 all of a sudd...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword by Andreas Busch

- Foreword by Günter Stock

- Preface

- Quotes

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Modern Biopharmaceuticals: Research is the Best Medicine – Sanitas Summum Bonus

- Part II: Modern Biopharmaceutical Development Using Stem Cells, Tissues, and Whole Animals

- Part III: Innovative Development Tools for Modern Biopharmaceuticals

- Part IV: The Rise of Monoclonal Antibodies – The Premium Class of Biopharmaceuticals

- Part V: Smart Solutions for Global Challanges – Vaccine-Based Biopharmaceuticals

- Part VI: Modern Biopharmaceuticals – The Holy Grail for Health and Wealth

- Part VII: From Innovative Tools to Improved Therapies – The Success of Second-Generation Biopharmaceuticals

- Part VIII: Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing and Downstream Processing – How to Uncork Bottlenecks

- Index