![]()

Chapter 1

What is a Decision, or What Does Decision Theory Have to Teach Us?

Si l’on observe ensuite que dans les choses même qui ne peuvent être soumises au calcul, elle [la théorie des probabilités] donne les aperçus les plus sûrs qui puissent nous guider dans nos jugements, et qu’elle nous apprend à nous garantir des illusions qui souvent nous égarent; on verra qu’il n’est point de science plus digne de nos méditations, et dont les résultats soient plus utiles.

“…if we observe that even when dealing with things that cannot be subjected to this calculus, it [the probability theory] gives the surest insight that can guide us in our judgment and teaches us to keep ourselves from the illusions that often mislead us, we will then realize that there is no other science that is more worthy of our meditation, nor whose results are more useful.”

P.S. Laplace, Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1814.

“Nothing ventured, nothing gained”

Common wisdom

1.1. Actions and events

Let us begin our discussion with an example.

EXAMPLE 1.1.— You are the CEO of a small company which manufactures faucets, and you are considering increasing your production capacity. In your cogitation, you consider that you could construct a new building next door to your existing factory (option a), construct a new building in Nowheresville where the local council is offering a viable plot of land (option b), or buy the business of one of your competitors who wishes to retire (option c).

These are the three possible options. In decision theory, each of these options is called an action.

DEFINITION.— An action, or an alternative, is one of the possibilities for acting which depends on the decision-maker and on him alone.

We can see that the meaning of the word action in decision theory corresponds, grosso modo, to the usage made of it in everyday language. The important point is that as soon as the movement which is under consideration does not depend only on the decision-maker, it is no longer an action.

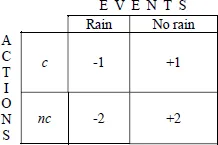

EXAMPLE 1.2.— You are preparing your backpack to go off on a trip to the mountains, and you have the choice between taking your coat in case it rains or leaving it behind. You are faced with two possible alternatives: c to take the coat, nc not to take it. Now, let us attempt to evaluate the result of your decision. If it rains and you have not brought the coat, your satisfaction is -2; if the weather is pleasant and you have avoided having to carry the coat, your satisfaction is +2; if you have brought the coat and the weather is pleasant, your satisfaction is +1; and it is -1 if you have brought the coat and it rains.

The fact of whether or not it rains is called an event, and as in the above example, whoever or whatever “controls” the event is called nature. Certain religions might say it was God, but scientists prefer the neutral term “nature”. In example 1.2, there are only two events: either it rains or it does not.

DEFINITION.— The term event is used to describe a movement of nature over which, by definition, the decision-maker has no control.

The situation is fairly simple: there is you, the decision-maker, who has total power to choose and to put your actions into effect, and there is nature, which “controls” the events.

Going back to example 1.2, we have seen that depending on the events, the decision-maker is more or less satisfied. The situation can be represented in a table.

DEFINITION.— We use the term decision matrix to denote the table showing the decision-maker’s satisfaction depending on the actions chosen and on the ensuing events.

Generally, in decision theory, we consider that the decision-maker’s satisfaction can be expressed as a function

u (for utility) of

A × ε in

(the ensemble of real facts) where

A is the ensemble of alternatives and

ε the ensemb;le of events. In our example: u(

c, rain) = −1.

We now have the building blocks for attempting to classify decisions. Let us consider Table 1.1: if it rains, action c is better, but if it does not rain, nc is the better option. We say that neither row dominates the other.

DEFINITION.— An action a dominates action a′ if, for every event e∈ε, u(a,e)≥u(a′,e).

When no action dominates the others, it is impossible to say which option is the best. The fact is that we are missing something — a representation of the future, because the decision concerns the future, as we have already seen.

There are many ways to represent the future, but that which has become most widely used since the 17th Century is probability-based modeling. It was originally modeling of uncertainty in games of chance which led to measuring the chance of an event occurring. For instance, what is the probability of the event of “throwing a five” when you throw a die with six faces? It is one chance in six. If the die is normal, this is an objective probability, i.e. if you throw the die a great many times, the number of “fives” obtained will be around 1/6 of the number of throws.

DEFINITION.— The term event denotes the realization of one of the possible states of the future. The ensemble of possible events is called a universe.

We may, however, ask ourselves whether it is truly realistic to separate the world into actions and events. There are actions which can modify events. For instance, if the action of a CEO consists of fixing a price and if the events are the reactions of the competitors, it is clear that the two cannot be separated — especially in an oligopoly; in order to analyze this case, we have need of other models, which stem from game theory. In general, the separation of the decision-maker and the environment — including the social environment — is merely a simplistic hypothesis (see [BOL 79] for a clearly-argued critique of this type of modeling), but it is a hypothesis which is necessary if we wish to shed an analytical light on decision-making and rationality.

To come back to this question in a more limited framework, Gilboa and Schmeidler [GIL 95] give examples of decision-making where separation between action and event does not yield a reflective framework which enables the problem in question to be truly solved. The first case is that of a CEO, attempting to recruit a salesperson. The possible alternatives are the candidates. In this case, the events are constructed rather than unfolding naturally. The “states of the world” represent the candidates’ qualities — e.g. honesty, performance, mobility, etc. Describing the states of the world entails knowing all the qualities of all the candidates in accordance with every criterion. There is uncertainty concerning whether or not the candidates actually have the qualities they are assumed to have — an uncertainty which the decision-makers attempt to reduce as much as possible by way of information searching. In this case, the multi-criterion decision-making framework (see Chapter 5) is a far more realistic way of approaching the problem.

It may be important at this point to give an idea of the paradoxes which arise if the model is not correctly implemented. Consider the following example, where the decision consists of choosing between two horses, “Lord of the Losers” and “Bag o’ Bones”. Which of the two models is the right one? (See [POU 88]).

Table 1.2. Comparison of two models

| My horse wins | My horse loses |

| Bet on Lord of the Losers | 50 | −5 |

| Bet on Bag o’ Bones | 45 | −6 |

Model 1

| Lord of the Losers wins | Bag o’ Bones wins |

| Bet on Lord of the Losers | 50 | −5 |

| Bet on Bag o’ Bones | −6 | 45 |

Model 2

According to the first model, we must always bet on Lord of the Losers, because he dominates the game. (Is the same true when he has a leg in plaster?) In the second model, it depends on the probability: we must bet on Bag o’ Bones if the probability of Lord of the Losers winning is less than 50/106. Thus, the model works well so long as we choose the right model. In the first model, the actions and events are linked by the adjective “my” in “my horse wins/loses”, which prevents the correct modeling of the second model.

1.2. Probabilities

When we wish to model a future phen...