![]()

PART 1

General Principles of Radiation Oncology

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Palliative Radiation Oncology

Joshua Jones

Palliative Care Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Introduction

A simple chronology of scientific and technologic developments belies the complexity of the history of palliative radiotherapy. The diversity of palliative radiation treatments utilized today reflects a dichotomy evident in the earliest days of therapeutic radiation, namely that radiation can be utilized to extend survival or to address anticipated or current symptoms. However, the line between “curative” and “palliative” treatments is not always obvious. Furthermore, even “palliative” radiotherapy has an impact on local tumor control, potentially improving survival and complicating the balance between effective and durable palliation with possible short- or long-term side effects of therapy. This introduction provides a basic overview of developments in the history of radiation therapy that continue to inform the complex thinking on how best to palliate symptoms of advanced cancer with radiation therapy.

The Early Years

Within a few short months of Wilhelm Roentgen’s publication of his monumental discovery in January 1896, several early pioneers around the world began treating patients with the newly discovered X-rays [1]. Early reports detailed treatments of various conditions of the hair, skin (lupus and “rodent ulcers”) and “epitheliomata,” primarily cancers of the skin, breast, and head and neck [2] (Figure 1.1). Other early reports, as championed by Emile Grubbe in a 1902 review, touted both the cure of malignancy as well as “remarkable results” in “incurable cases” including relief of pain, cessation of hemorrhage or discharge and prolongation of life without suffering [3]. Optimism was high that X-rays would soon be able to transform many of the “incurable cases” to curable.

In his 1902 textbook, Francis Williams, one of the early pioneers from Boston, described his optimism that radiation therapy would eliminate growths on the skin: “The best way of avoiding the larger forms of external growths is by prevention; that is, by submitting all early new growths, whether they seem of a dangerous nature or not, to the X-rays. No harm can follow their use in proper hands and much good will result from this course [4].” He went on to state that, while “internal new growths” could not yet be treated with X-ray therapy, he was optimistic that such treatments would be possible in the future. In this setting, he put forward an early treatment algorithm for cancer that divided tumors into those treatable with X-ray therapy, those treatable with surgery and X-ray therapy post-operatively, and those amenable to palliation with X-ray therapy. He further described that the specific treatment varied from patient to patient but could be standardized between patients based on exposure time and skin erythema.

Other early radiology textbooks took a more measured approach to X-ray therapy. Leopold Freund’s 1904 textbook described in great detail the physics of X-rays and again summarized the early clinical outcomes. In his description of X-ray therapy, he highlighted the risks of side effects, including ulceration, with prolonged exposures to X-rays without sufficient breaks. He noted that the mechanism of action of radiation was still not understood, with theories at the time focusing on the electrical effects of radiation, the production of ozone, or perhaps direct effects of the X-rays themselves. Freund highlighted early attempts at measuring the dose of radiation delivered, emphasizing the necessity of future standardization of dosing and research into the physiologic effects of X-ray therapy [2]. As foreshadowed in the textbooks of Williams and Freund, early research in radiation therapy focused on clinical descriptions of the effectiveness of X-rays contrasted with side effects of X-rays, the determination of what disease could be effectively treated with radiotherapy, the standardization of equipment and measurement of dose, and attempts to understand the physiologic effects of X-ray therapy.

The history of radium therapy in many ways parallels developments in the history of Roentgen ray therapy. After the discovery of radium by the Curies in 1898, the effects of radium on the skin were described by Walkoff and Giesel in early 1901. This description was offered prior to the famed “Becquerel burn” in which Henri Becquerel noticed a skin burn after leaving a piece of radium in a pocket of his waistcoat [5]. Radium quickly found many formulations of use: as a poultice on the skin, as an “emanation” that could be inhaled, consumed in water, or absorbed via a bath, or in needles that could be implanted deep into the body [6]. The reports of the effectiveness of radium therapy appeared more slowly than those of X-ray therapy, however, owing to its cost and rarity.

The future of radium mining in the United States for use in medical treatments was pushed forward by the incorporation of the National Radium Institute in 1913, a joint venture by a Johns Hopkins physician, Howard Kelly, a philanthropist and mine executive, James Douglas, and the US Bureau of Mines. However, the notion of protecting lands for radium mining was vigorously debated in Congress in 1914 and 1915. The debate focused on therapeutic uses of radium, risks to radium workers, and the nuances of the economics, given that radium had previously been exported for processing and re-imported at much higher cost. The debate over the use of radium treatments escaped from the medical literature into the public consciousness [7]. Kelly championed the curative effects of radium therapy, but there was significant opposition to the use of radium in medicine due to a reported lack of efficacy. In 1915, Senator John Works from California made a speech before the United States Senate urging no further use of radium in the treatment of cancer:

The claim that radium is a cure for cancer has been effectually exploded by actual experience and declared by numerous competent authorities on the subject to be ineffectual for that purpose … If radium is not a specific [cure] for cancer, the passage of the radium bill would be an act of inhuman cruelty. It would be taken as an indorsement [sic] by the Government of that remedy and would bring additional suffering, disappointment, and sorrow to sufferers from the disease, their relatives and friends, and bring no compensating results [8].

In spite of these concerns and the growth and subsequent decline of popular radium treatments including radium spas and radium baths in the 1920s and 1930s, radium therapy continued to grow and develop an evidence base for both the curative treatment of cancer and the relief of symptoms from advanced cancer.

With publicity surrounding the development of cancer and later death among radium dial workers (the first death coming in 1921), radium therapy was again under attack in the early 1920s. In 1922, in an address to the Medical Society of New York, Kelly sought to “emphasize the palliative results.” As reported in the Medical Record, Kelly believed “If he could do nothing more than improve and relieve his patients, as he had been able to do, never curing one, it would still be worth his while to continue this work [9].” Palliative radiotherapy, with the explicit goal of palliation and not cure, had been recognized as a legitimate area of study.

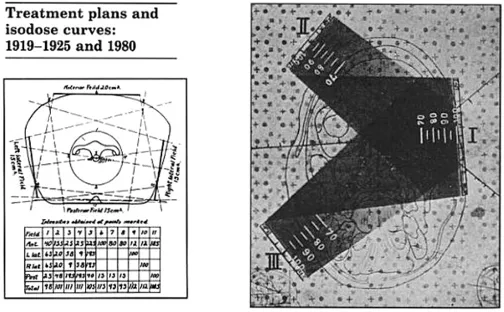

Fractionation

A challenge that has persisted through the history of the treatment of cancer is how best to improve the therapeutic ratio: specifically, how best to target cancer cells while minimizing damage to surrounding normal tissue. In the earliest years of radiation therapy, minimizing toxicity to the skin was a significant challenge as the kilovoltage X-rays delivered maximum dose to the skin, creating brisk erythema, desquamation, and even ulceration (Figure 1.2). In the 1920s, Regaud conducted a series of experiments demonstrating that dividing a total dose of radiation into smaller fractions could obtain the same target effect (sterilization of a ram) while minimizing skin damage [10]. These observations were later applied by Coutard in the radiotherapy clinic to the treatment of cancer, both superficial and deep tumors. By the mid-1930s, the concept of fractionating radiotherapy to give three to five doses per week over a period of 5 to 6 weeks had become a standard method for the protection of normal tissues [11].

After Coutard’s publication, studies demonstrating the efficacy of fractionated radiotherapy also suggested palliation from radiotherapy could be achieved with lower delivered doses. One specific article, published by Lenz and Freid in Annals of Surgery in 1931, highlighted challenges with fractionation and set forth suggestions for palliation of symptomatic metastases from breast cancer. The study explored the natural history of breast cancer metastases to the brain, spine, and bones and the effect of radiotherapy in the treatment of these metastases [12]. The study retrospectively analyzed two time periods in the course of illness: the pre-terminal period (up to one year prior to death or two-thirds of the time of illness if the patient lived less than one year) and the terminal period (the final one-third of time of illness if the patient lived less than one year). Lenz correlated the impact of grade of ...