![]()

Chapter 1

A Fractal World

“Fractals are mathematical objects, whether naturally or man made,

which can be described as irregular, coarse, porous or fragmented,

and which, furthermore, possess these properties

to the same extent on all scales.”

Benoît Mandelbrot, 1975

The diversity, coarseness and irregularity of land are all at the heart of geographical projects. It is therefore not surprising that the fractal approach enriches this discipline, since the fractal dimension was originally a measure of an object’s irregularity and shape, as emphasized by the definition provided by B. Mandelbrot [MAN 75]. The calculation of a fractal dimension therefore enables the irregularity and, in a way, the complexity of all land to be defined.

Following a rapid and therefore mostly incomplete French-language census of the fractal approach in geography in section 1.1, in section 1.2 we show how this approach, which is initially focused on shape, is extended to mechanisms, processes and functional structures that are realized through a series of frequential data or a rank-size rule. The links between fractals and power law are detailed in section 1.3. Without aiming to be completely historical, this chapter highlights the pioneering works of the French-speaking geographers who set the fractal approach in motion. More recent research is referenced in later chapters.

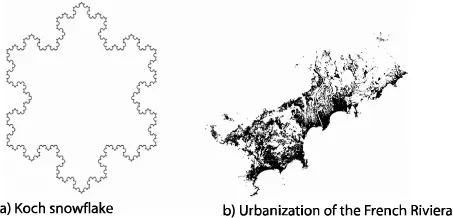

Before tackling these issues, we recall that a fractal object possesses a number of properties. It is certainly irregular and fragmented, as emphasized in all known definitions, but is also either auto-similar or self-affine. An object that is irregular without being auto-similar or self-affine is not a fractal. An auto-similar phenomenon has perfectly identical sections throughout. It is often constructed through iteration of a basic pattern, as with the Koch snowflake (see Figure 1.1). Occasionally, the initial pattern is deformed in one or more directions. The phenomenon is then no longer auto-similar, but self-affine. The urbanization of the French Riviera (see Figure 1.1), which is spread along axes that are parallel and perpendicular to the coast line, is an example of this.

Additionally, fractals go hand-in-hand with power laws, since these are the only scale-invariant laws. Finally, the fractal dimension is always greater than the topological dimension. In practice, this fractal dimension is calculated from the value of the power law slope; and yet this slope, which is also known as a scaling parameter, should not be confused with a fractal dimension.

1.1. Fractals pervade into geography

In his early works, in order to define a fractal, B. Mandelbrot made reference to familiar geographical objects. In his widely-available publication Les Objets Fractals: Forme, Hasard et Dimension (Fractals: Forms, Chance and Dimension) [MAN 75], he visited or revisited some geographical problems, such as the length of the Brittany coast lines, which were often tackled in earlier articles, particularly by L.F. Richardson [RIC 61]. Then, in The Fractal Geometry of Nature [MAN 77], he devoted whole chapters to hydrographical networks and relief forms.

His contribution was not limited to the study of spatial morphology; he was also concerned with evolution and rhythm, and therefore temporal laws and morphogenesis. In a short time he applied fractal formalism to time series, which were representative of process, by publishing some innovative works on stock market trends, such as the evolution of the price of cotton.

Following these pioneering works, it is now accepted that most terrestrial forms, as well as their origins, are fractal. No geographical phenomena are excluded from this approach. In the examples that follow, we provide academic and traditional distinctions, both in physical and human geography, although the fractal approach abolishes this distinction and reunites these two categories of objects.

1.1.1. From geosciences to physical geography

In physical geography this reasoning, which has become the norm in the geosciences [DUB 95, KRU 94, SHO 89], is now being used in climatology, hydrology, biogeography and geomorphology research.

1.1.1.1. The omnipresence of fractals in meteorology — climatology and hydrology

Geography is not insular or closed. Geographers communicate with researchers from similar disciplines, who often show the way forward. For example, since too few geographers and climatologists had taken ownership of the fractal paradigm [DAU 98], in a short time whole meteorological colleges were devoting all their efforts to writing articles and theses [BIA 04, HAL 01, HUB 89, LAD 93, LOV 82, SCH 87, TES 93]. Thus we had the opportunity to serve on the thesis jury of P.H. Ladoy, who drew our attention to the fractality of climatological variables.

Since his first works, S. Lovejoy [LOV 82] has demonstrated that the areas and perimeters of cloud formations are fractal. Since then, meteorologists have extended this fractal formalism to other climatic descriptors, but also to pluviometric and thermal rhythms, since the scale dependence on meteorological structures is permanent. The scale ratio can easily reach 109, from the size of a drop of water to that of Hadley cells.

More recently, meteorologists have been making good use of multifractal formalism in order to understand the organization of temperature and pressure fields. They have emphasized that fractal formalism applies to simple bodies, but that the meteorologist nearly always associates a measurement with these bodies. Temperature, pressure and rain fields bring intensity to a body of weather stations. It is thus useful to apply multifractal formalism to these fields, as with population density charts or commercial areas. We will develop this area in Chapters 3 and 6. Additionally, meteorologists are at the heart of the interest in relative codimension, which we define in Chapter 3.

Despite everything, it was in geohydrology that fractals were perceived to be most relevant, notably in France with the works of D. Delahaye [DEL 02] and P.H. Martin [MAR 04]. Without a doubt, we need to recognize the significance of previous research carried out by R.E. Horton [HOR 45] and A.N. Stralher [STR 45] on the charting of river systems. This opened the way to a fractal vision of this discipline, as well as the need to promote effective flood management, taking into account not just a simple river section, but the whole hydrographic network of a river basin. This operational necessity has forced recourse to multiscale practices, which rely on fractal formalism.

Very soon, hydrologists established a power law between the length of river networks and their river basin area. Hack’s law links the length of the principal drain to the surface of the basin using a power law. Recently, some algorithms, which have been incorporated into GIS (Geographical Information Systems) geographical systems, have calculated the fractal dimensions of river networks based on digital terrain modeling. Thus J. Douvinet et al. [DOU 08] have shown that the relationship between the maximum surface flow and the basin surface follows a power law where the scaling parameter is equal to 0.54. They have thus proposed a new set of indices, which show the effect of basin size in brackets in order to compare the efficiency of river networks. Furthermore, these hydrological geographers are not confined to their own discipline, but invest in many others, as many of them are also talented karstologists.

1.1.1.2. Rarer pioneering works from geomorphology and ecology

Notwithstanding recent studies, which have occasionally been conducted by atypical researchers, French geomorphology has long remained on the fringes of this vast current. Exceptions to this are H. Regnauld [REG 93] and the Caen geomorphologists [HAU 02, DEL 02], who as a result of the fractal approach discovered a new set of fault directions north-west of the Paris Basin. These faults angled 90-100 north have complicated the traditional model of a tectonic evolution, which traditionally attached significance to single faults in the Armorican and Variscan directions.

This indifference to geomorphology is all the more surprising as geomorphologists were among the first to appreciate the role of fractals. The autosimilar characteristic of relief forms was implicitly accepted by all geologists who would use a hammer to visualize the scale of phenomena recreated in photographic documents produced by them.

An article by M.F. Goodchild and D.M. Mark [GOO 87] discussed the suitability of the fractal approach in geomorphology, not hesitating to criticize Mandelbrot’s rather “hasty” generalizations. While recognizing the interest in descriptions of relief irregularity using the fractal dimension, these authors detailed the limitations of the fractional Brownian model, which we will cover in depth in Chapter 2, in understanding the organization of natural terrestrial forms.

Furthermore, the number of related fractal studies into earthquakes can be counted in the hundreds. The Gutenberg-Richter law on earthquake magnitude and the Omori-Utsu law, which measures aftershocks after an earthquake, are both power laws. The same applies to spatial fault distributions and the epicenters of earth tremors [DUB 95].

Geologists are not content with descriptive research. They have linked the fractality of the seismicity of various physical models, particularly those relating to percolation [ALL 82] and ultimately critical self-organization theory. They have proved that seismicity and earth tremors are characterized by the absence of a dominant scale. All temporal and spatial scales contribute equally to global seismicity.

Fractal simulation was first applied to relief forms. There are computer programs available in the pioneering works edited by N.S.-N. Lam and L. De Cola [LAM 93]. Also, the beautiful relief image simulations, which were used to illustrate works published in the 1990s, have undeniably contributed to the success of fractals, bearing as they did a striking resemblance to the true relief forms that geomorphologists explored during their field visits.

Finally, and still on the subject of geomorphology, the Canadian school very quickly became interested in the fractal paradigm. It continues to provide quality output, as testified by A. Beaulieu’s thesis on fractal anisotropy [BEA 04], which followed in the footsteps of A. Robert and A.G. Roy [ROB 93] and the geologist H. Gaonac’h [GAO 92]. This examined the fractal characteristics of volcanic lava casts from samples taken from the peak of the furnace and from Etna. However, it was not able to provide a satisfactory explanation.

In biogeography, the works of geographers are even less commonplace, despite the early studies by P.A. Burrough [BUR 83a] on soil distribution and D.M. Mark [MAR 84] on the branched organization of coral. They sometimes compared the advantages of the fractal approach with the geostatistical treatment.

Some ecologists and biologists do, however, diffuse the fractal approach in their disciplines [BAS 98, BUR 99, CHA 99]. They generally calculate fractal dimensions using the variogram method, since they have control over the formalism of geostatistics. We also owe a debt of thanks to marine biologist L. Seuront [SEU 10], for producing an excellent manual on fractal and multifractal formalism, which was influential when writing Chapter 2 of this book.

In addition, in France, it is worth mentioning the originality of the works of the “Montpelier school” in the field of fractal simulation of vegetation. They have simulated the seasonal and year-on-year evolution of vegetation landscapes, demonstrated that the fractal approach sometimes bypasses the area of fundamental research, and have offered practical methods in environmental management (Chapter 9).

1.1.2. Urban geography: a big beneficiary

Within human geography, the fractal paradigm has principally conquered the field of urban studies and the area of networks. The fractal methodology does however, remain applicable to other fields of geographical knowledge.

1.1.2.1. The fractality of perimeters and urban tissue

Fractal dimension calculation is central to innovative research into urban forms. After numerous articles, M. Batty and P.A. Longley [BAT 94] devoted a substantial publication to this. They were not simply content to describe urban for...