Remote Sensing Imagery

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Remote Sensing Imagery

About this book

Dedicated to remote sensing images, from their acquisition to their use in various applications, this book covers the global lifecycle of images, including sensors and acquisition systems, applications such as movement monitoring or data assimilation, and image and data processing.

It is organized in three main parts. The first part presents technological information about remote sensing (choice of satellite orbit and sensors) and elements of physics related to sensing (optics and microwave propagation). The second part presents image processing algorithms and their specificities for radar or optical, multi and hyper-spectral images. The final part is devoted to applications: change detection and analysis of time series, elevation measurement, displacement measurement and data assimilation.

Offering a comprehensive survey of the domain of remote sensing imagery with a multi-disciplinary approach, this book is suitable for graduate students and engineers, with backgrounds either in computer science and applied math (signal and image processing) or geo-physics.

About the Authors

Florence Tupin is Professor at Telecom ParisTech, France. Her research interests include remote sensing imagery, image analysis and interpretation, three-dimensional reconstruction, and synthetic aperture radar, especially for urban remote sensing applications.

Jordi Inglada works at the Centre National d'Études Spatiales (French Space Agency), Toulouse, France, in the field of remote sensing image processing at the CESBIO laboratory. He is in charge of the development of image processing algorithms for the operational exploitation of Earth observation images, mainly in the field of multi-temporal image analysis for land use and cover change.

Jean-Marie Nicolas is Professor at Telecom ParisTech in the Signal and Imaging department. His research interests include the modeling and processing of synthetic aperture radar images.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Systems and Constraints

1.1. Satellite systems

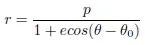

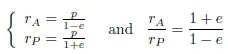

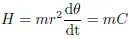

1.2. Kepler’s and Newton’s laws

1.3. The quasi-circular orbits of remote sensing satellites

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Part 1: Systems, Sensors and Acquisitions

- Part 2: Physics and Data Processing

- Part 3: Applications: Measures, Extraction, Combination and Information Fusion

- Bibliography

- List of Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app