Lithium Batteries and other Electrochemical Storage Systems

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Lithium Batteries and other Electrochemical Storage Systems

About this book

Lithium batteries were introduced relatively recently in comparison to lead- or nickel-based batteries, which have been around for over 100 years. Nevertheless, in the space of 20 years, they have acquired a considerable market share – particularly for the supply of mobile devices. We are still a long way from exhausting the possibilities that they offer. Numerous projects will undoubtedly further improve their performances in the years to come. For large-scale storage systems, other types of batteries are also worthy of consideration: hot batteries and redox flow systems, for example.

This book begins by showing the diversity of applications for secondary batteries and the main characteristics required of them in terms of storage. After a chapter presenting the definitions and measuring methods used in the world of electrochemical storage, and another that gives examples of the applications of batteries, the remainder of this book is given over to describing the batteries developed recently (end of the 20th Century) which are now being commercialized, as well as those with a bright future. The authors also touch upon the increasingly rapid evolution of the technologies, particularly regarding lithium batteries, for which the avenues of research are extremely varied.

Contents

Part 1. Storage Requirements Characteristics of Secondary Batteries Examples of Use

1. Breakdown of Storage Requirements.

2. Definitions and Measuring Methods.

3. Practical Examples Using Electrochemical Storage.

Part 2. Lithium Batteries

4. Introduction to Lithium Batteries.

5. The Basic Elements in Lithium-ion Batteries: Electrodes, Electrolytes and Collectors.

6. Usual Lithium-ion Batteries.

7. Present and Future Developments Regarding Lithium-ion Batteries.

8. Lithium-Metal Polymer Batteries.

9. Lithium-Sulfur Batteries.

10. Lithium-Air Batteries.

11. Lithium Resources.

Part 3. Other Types of Batteries

12. Other Types of Batteries.

About the Authors

Christian Glaize is Professor at the University of Montpellier, France. He is also Researcher in the Materials and Energy Group (GEM) of the Institute for Electronics (IES), France.

Sylvie Geniès is a project manager at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives) in Grenoble, France.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART 1

Storage Requirements Characteristics of Secondary Batteries Examples of Use

Chapter 1

Breakdown of Storage Requirements

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Domains of application for energy storage

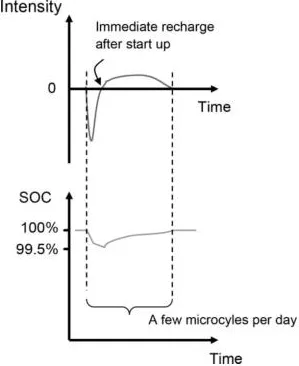

1.2.1. Starter batteries

1.2.2. Traction batteries

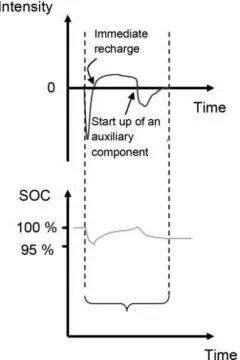

1.2.2.1. Vehicle batteries without brake energy recovery

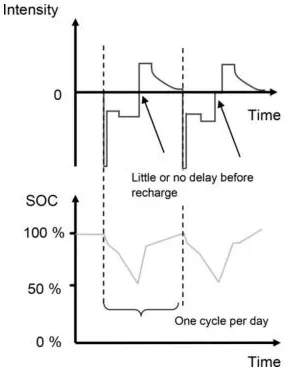

1.2.2.2. Vehicle batteries with brake energy recovery

1.2.2.2.1. Hybrid vehicle batteries

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART 1: Storage Requirements Characteristics of Secondary Batteries Examples of Use

- PART 2: Lithium Batteries

- PART 3: Other Types of Batteries

- Conclusion

- Index