![]()

CHAPTER 1

ANTIMICROBIAL PACKAGING POLYMERS. A GENERAL INTRODUCTION

JOSÉ M. LAGARÓN, MARÍA J. OCIO, and AMPARO LÓPEZ-RUBIO

Instituto de Agroquímica y Tecnología de Alimentos (IATA), CSIC, Valencia, Spain

CONTENTS

1.1 Pathogens in Food: Public Health Importance

1.2 Primary Contamination and Its Causes

1.2.1 Salmonella spp

1.2.2 L. monocytogenes

1.2.3 S. aureus

1.2.4 C. jejuni

1.2.5 E. coli O157:H7

1.3 Prevention and Control

1.4 Antimicrobial Agents for Food Preservation

1.5 Methods to Determine the Antimicrobial Activity

1.6 Plastics and Bioplastics in Packaging

1.7 Antimicrobials in Polymers

1.8 Conclusions

References

This chapter introduces in a general and brief fashion the subjects discussed across the book. Albeit the concepts can be generally considered, it has an application perspective that relates more intensely to the food area. This is because antimicrobials, thanks to the recent publication of the European Commission regulation on active and intelligent materials and articles intended to come into contact with food (EC 450/2009) as well as to the increasing number of submissions to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), are attracting a lot of new academic and industrial interest for implementation into plastic packaging materials.

1.1 PATHOGENS IN FOOD: PUBLIC HEALTH IMPORTANCE

Without a doubt, the most relevant sectors regarding the seriousness of microbial contamination are hospitals and medical equipment and foods. Hence, antimicrobials have traditionally been of great relevance to these areas. Foods are perhaps attracting even greater general attention in particular nowadays because they constitute a permanent part of our daily life and are increasingly making use of plastic packaging for their presentation to the consumer. Infections and intoxications associated with consumption of foods are a growing concern worldwide. In this regard, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) report annually on the main agents causing food-borne toxic infections. The results suggest that in recent years there has been a slight increase in food-borne diseases in many parts of the world and that the emergence of new or newly recognized food-borne problems have been identified and associated with consumption of foods. According to the WHO [1, 2], one of the main reasons for this increase is that the microbial population have adapted through natural selection leading to the development of antibiotic resistance, acquisition of new virulence factors, or changes in the ability to survive in adverse environmental conditions. In addition, the change of population dietary habits produced by the growing demand for prepared foods and minimally processed foods has contributed significantly in increasing the number of outbreaks of food-borne illnesses.

1.2 PRIMARY CONTAMINATION AND ITS CAUSES

Most pathogenic bacteria associated with food-borne diseases are zoonotic (animal origin), and their carriers are usually healthy animals from which are transmitted to a wide variety of foods such as Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, or Campylobacter jejuni. Other pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes are widely distributed in the environment or are part of the natural microbiota of humans as Staphylococcus aureus. In these two last cases, food contamination occurs during processing as a result of failures of hygienic practices in the food chain.

Farm animals usually acquire microbial hazards as a result of horizontal transmission from their environment. The principal sources are other infected animals, contaminated water, and wildlife such as birds or rodents. This horizontal transmission can be exacerbated by intensive husbandry, which promotes overcrowding and interferes with the maintenance of adequate hygiene to which animals are subjected in many farms [3, 4]. Finally, the products derived from these infected animals can reach the consumer at some point.

The rising incidence of microbial food-borne disease has focused attention on the sources of contamination. Because animal products have been directly responsible for more than the 50% of the total food-borne outbreaks in the 1990s, emphasis has been paid to these types of products such as meat, poultry, eggs, and milk [5]. Nevertheless, in recent years, the demand for fresh fruits and vegetables has increased in the industrial countries as a consequence of the awareness of the health benefits associated with eating fresh produce [6]. Nowadays, therefore, outbreaks of food-borne diseases have been increased probably because crops in the field can be contaminated with pathogens carried by farm animals and human beings. The main risk factors include proximity to irrigation wells and surface waterways exposed to feces from cattle and wildlife, exposure in fields to wild animals and their waste materials, and improperly composted animal manure used as fertilizer [7]. The public health implications are especially serious when the products affected are those usually consumed without cooking such as salad fruits and vegetables [8]. Although the frequency of food-borne outbreaks in gastrointestinal illness associated with fruit and vegetables seems to be low compared with products of animal origin, ready-to-eat fruit and vegetables requiring minimal or no further processing prior to consumption have been implicated as vehicles for transmission of infectious microorganisms. Even more, food-borne illnesses associated with fruit and vegetables seem to be increasing in many countries because of mainly the increase in global food distribution.

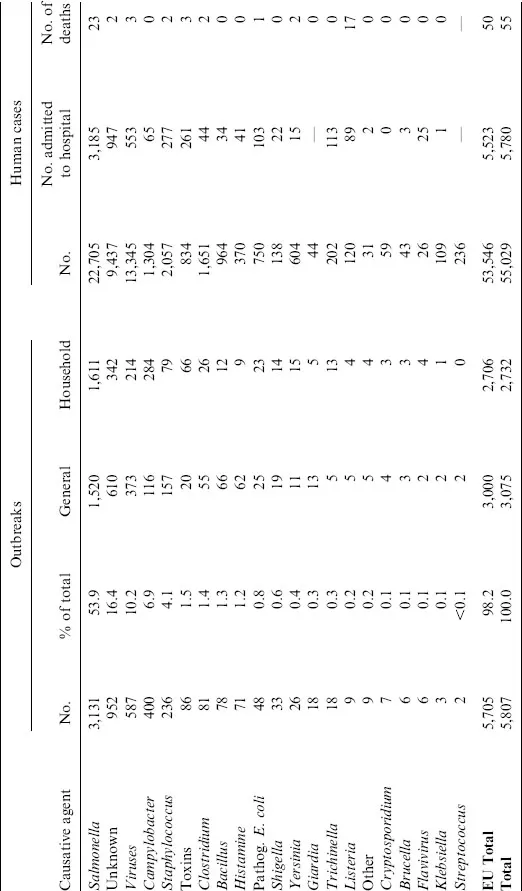

The last global report available from the European Union is from 2006. In this report, the number of food-borne outbreaks, causative agents, and number of affected people by these gastrointestinal illnesses were shown. For instance, in this year, 5,705 outbreaks involving a total of 53,568 people, resulting in 5,525 hospitalizations (10.3%) and 50 deaths (0.1%), were reported. Table 1.1 summarizes the number of reported food-borne outbreaks in the Europe Union (EU) in 2006. These results show that Salmonella was the food-borne pathogen most frequently recorded by the EU, although there has been a slight decline in recent years. Campylobacter infections are the second most common zoonotic agent, affecting 1,304 people (6.9%). S. aureus was the etiological agent of 4.1% of the outbreaks (236) and affected 2,057 people, causing two deaths. Verotoxic-producing E. coli was responsible for 0.8% of the outbreaks, and although it is one of the most harmful pathogens, it only caused one death. On average, Listeria was the most severe pathogen causing 9 outbreaks that affected 120 people, of which 74.2% (89) was hospitalized and 17 died. The most common food vehicle was eggs and egg products, which were responsible for 17.8% of these outbreaks, whereas unspecified meat was reported as the causative source in 10.3% of the outbreaks. Fish and fish products were the source of 4.6% and dairy products of 3.2% of the outbreaks [9].

TABLE 1.1 Causative agents responsible for foodborne outbreaks, 2006 (all countries)

Source: The EFSA Journal, 2007;130:252–352 [9].

Food-borne disease caused by microbiological hazards is a large and growing public health problem. Most countries with systems for reporting cases of food-borne diseases have documented significant increases over the past few decades in the incidence of diseases caused by microorganisms in foods, including Salmonella spp., S. aureus, C. jejuni, L. monocytogenes, or E. coli O157 among others.

1.2.1 Salmonella spp.

Salmonella spp. is a heterotrophic, mesophile, gram-negative bacteria that is worldwide one of the major infections transmitted via food ingestion, causing gastroenteritis, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, enteric fever, septicemia, and in severe cases even death [10]. In August 2005, 2,138 cases of salmonella gastroenteritis were reported to the National Centre for Epidemiology (CNE) in Spain. The reported cases were epidemiologically and microbiologically linked to a single brand of precooked, vacuum-packed roast chicken that was commercially distributed throughout Spain. Although it did not report any human deaths, this produced a substantial economic loss to the producing company.

1.2.2 L. monocytogenes

Another more harmful microorganism is L. monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen of particular concern in ready-to-eat (RTE) products because of its ability to survive and grow at refrigeration temperatures and of its capacity to tolerate high heat and high concentrations of salt [11]. Even after cleaning, a prevalence of L. monocytogenes of 10% was detected in surface samples of the investigated equipment of small Spanish processing plants of traditional fermented products [12]. L. monocytogenes causes food-borne listeriosis, a disease that occurs largely in pregnant woman and the elderly leading to illness, miscarriages, and death [13]. Recently, a Listeria outbreak linked to a meat product plant in Toronto has expanded to 26 cases, and 12 people have died, although it is not yet clear how many of the deaths were directly from the illness.

1.2.3 S. aureus

S. aureus is a gram-positive bacterium able to produce sufficient enterotoxins to cause illness from an inoculum size of ca. 105 CFU/mL. Although death from staphylococcal food poisoning is rare (0.03% of cases), it presents several symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal cramping. A wide range of foods is involved as sources of staphylococci food poisoning in restaurants where meals are previously prepared in a central chicken and subsequently transported. As S. aureus lives in the nasal membranes, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and so on, carriers or infected food handles may easily transmit these organisms to food. If food is contaminated and temperature abused before cooking, heating will destroy the bacteria, but heat-stable enterotoxin may remain and cause illness. A recent study conducted on determination of histamine in swordfish filets implicated in an incident of food-borne poisoning that caused illness in 43 victims in December 2004 in central Taiwan revealed that S. aureus seemed to be the histamine former strain [14].

1.2.4 C. jejuni

Campylobacter infection is estimated to be the leading cause of bacterial food-borne illness in the industrial countries, and food-borne transmission accounts for approximately 80% of all infections [15]. More than 90% of all human Campylobacter infections are caused by C. jejuni and C. coli. Natural reservoirs are wild birds, and chickens become colonized shortly after birth and are the most important source for human infection. C. jejuni is a gram-negative microaerophile, and its optimal grown conditions are a neutral pH and 41°C to 42°C of temperature. It has been frequently isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of wild birds, humans, and other mammals [16]. Human infections are normally attributed to consumption of contaminated uncooked poultry and cross-contamination from this source as well as to contact with cattle including consumption of beef and milk. Symptoms and signs usually include fever, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea as a mild illness but occasionally severe, leading to meningitis, pneumonia, miscarriage, and Guillain–Barré syndrome [17]. Deaths attributable to C. jejuni infection have been reported but rarely occur [18].

1.2.5 E. coli O157:H7

E. coli infection is transmitted to humans mainly through consumption of contaminated foods such as raw or undercooked meat and milk. Fecal contamination of water and other foods, as well as cross-contamination during handling, a...