- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Blackwell Companion to the Bible and Culture

About this book

The Blackwell Companion to the Bible and Culture provides readers with a concise, readable and scholarly introduction to twenty-first century approaches to the Bible.

- Consists of 30 articles written by distinguished specialists from around the world

- Draws on interdisciplinary and international examples to explore how the Bible has impacted on all the major social contexts where it has been influential – ancient, medieval and modern, world-wide

- Gives examples of how the Bible has influenced literature, art, music, history, religious studies, politics, ecology and sociology

- Each article is accompanied by a comprehensive bibliography

- Offers guidance on how to read the Bible and its many interpretations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Blackwell Companion to the Bible and Culture by John F. A. Sawyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Revealing the Past

1 The Ancient World

Philip R. Davies

2 The Patristic Period

Kate Cooper

3 The Middle Ages

Mary Dove

4 The Renaissance

Ilona N. Rashkow

5 The Reformation

Peter Matheson

6 The Counter-Reformation

Euan Cameron

7 The Modern World

John W. Rogerson

Philip R. Davies

2 The Patristic Period

Kate Cooper

3 The Middle Ages

Mary Dove

4 The Renaissance

Ilona N. Rashkow

5 The Reformation

Peter Matheson

6 The Counter-Reformation

Euan Cameron

7 The Modern World

John W. Rogerson

CHAPTER 1

The Ancient World

From the twenty-first century, we look at the ancient world through two pairs of eyes. One pair looks back over the sweep of human history to the civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia, Assyria, Persia, Greece and Rome, which played their successive roles in shaping our modern world. The other set of eyes looks through the Bible, seeing the ancient world through the lenses of Scripture, not only directly from its pages but also through two millennia of Christian culture that long ago lodged itself in the imperial capitals of Rome and Constantinople yet saw its prehistory in the Old Testament and its birth in the New. The museums, galleries and libraries of Western Christendom bulge with representations of scenes from a biblical world dressed in ancient, medieval or modern garb.

Although the rediscovery of ancient Egypt, for which we should thank Napoleon, preceded by a century and a half the unearthing of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia – Babylon, Nineveh, Ur, Caleh – these cities captured the modern imagination because they were known to us from the Bible. These discoveries heralded the phenomenon of ‘biblical archaeology’, and the kind of cultural imperialism that brought ancient Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Egypt into the ‘biblical world’. Although the ‘Holy Land’ was a small region of little consequence to these great powers, the biblical vision of Jerusalem as the centre stage of divine history has been firmly embedded in our cultural consciousness. The ‘biblical world’ can therefore mean both the real world from which the Bible comes and also the world that it evokes. In this chapter we shall look primarily at the former, with a final glimpse of the ancient world in the Bible.

How does one introduce ‘the ancient world’ in a short space? Obviously with the aid of great deal of generalization and selectivity. What follows is obviously painted with a very broad brush, focusing on major motifs such as kingship, city and empire – institutions that are not only political, but also economic and social configurations. The growth and succession of monarchy, cities and empires both dominated the world of the Bible but also occupy much of its attention. The climax of this ancient world’s history is the interpenetration of two spheres: the ‘ancient Near East’ and the ‘Greek’, effected by Alexander’s conquest of Persia. The ‘kingship’, by then lost to the Greeks, was revived in an ancient Near Eastern form, Greek-style cities sprang up, and a civilization called ‘Hellenism’ developed. This great cultural empire fell under the political governance of Rome, under which it continued to flourish, while Rome itself, after years of republic, adopted a form of age-old ancient Near Eastern kingship.

A Historical Sketch

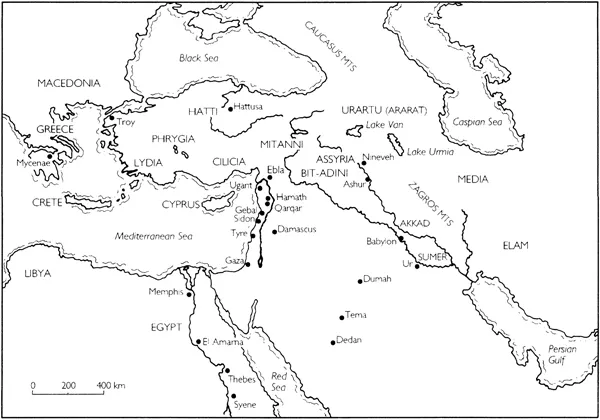

The worlds of the eastern Mediterranean and the ancient Near East were contiguous both geographically and chronologically. The eastern seaboard of the Mediterranean lay at the intersection of a maritime world and a large stretch of habitable land from Egypt to Mesopotamia, the so-called ‘Fertile Crescent’, curving around the Arabian desert to the south-east and fringed on the north by various mountain ranges (see Figure 1.1). Egypt and the cities of Phoenicia were engaged in sea trading with each other and with various peoples that we can loosely call ‘Greek’ (Minoans, Myceneans, Dorians, Ionians and Aeolians) from very early times. The Greeks colonized parts of Asia Minor and islands in the eastern Mediterranean, and the Phoenicians founded colonies in North Africa and eventually Spain also. What was exchanged in this trade included not only wine, olive oil, papyrus, pottery and cedar wood, but ‘invisibles’ such as the alphabet, stories, myths and legends. Traders (including tribes who specialized in trading caravans, such as the Ishmaelites and Edomites) and their wares penetrated eastward via Damascus and the Euphrates and across southern Palestine to the Red Sea. During the second millennium BCE, Egypt was in control of Syria and Palestine; but during the Iron Age and up to the advent of Alexander, its grip loosened and political power lay well away from the Mediterranean, in Mesopotamia.

Figure 1.1 The Fertile Crescent

The ancient Near East

The word ‘civilization’ derives from the Latin civitas, ‘city’, and civilization is inseparable from urbanization. Cities mark the emergence of human diversity, a proliferation of social functions. They also mark a differentiation of power, for cities and their activities (in the ancient Near East at any rate) represent a form of social cooperation that is always governed by a ruler: major building projects, organized warfare, taxation, bureaucracy. In Mesopotamia, as throughout the ancient Near East (except Egypt) during the Bronze Age (c.3000–1200 BCE), cities were individual states, each comprising not only the fortified nucleus but also a rural hinterland of farms and villages, forming an interdependent economic, social and political system. Within the ‘city’ proper lay political and ideological power: administration, military resources, temples, the apparatus of ‘kingship’. Economically, the ancient city was a consumer rather than a creator of wealth, its income drawn mostly from the labours of the farmers, who were freeholders, tenants or slaves. Farmers comprised well over nine-tenths of the population; but they have left us little trace of their mud-brick houses, their myths and legends, their places of worship, their daily lives. Their houses have mostly disintegrated, their stories, customs and rituals left only in their burials, and whatever has survived of their material culture. We see them only occasionally as captives in war on an Assyrian relief or as labourers in Egyptian scenes of building enterprises. (We glimpse them in the Bible, but not fully; we know mostly about kings, priests, prophets and patriarchs.) They subsisted as the climate permitted; their surpluses went to their ruler, the king and to the gods (the temple and priests), who were usually under royal control. In return, the ruler defended them (as far as he could) from attack and invasion, which could also destroy their harvest and their livelihood.

We know more of the rulers than the ruled: we can visit the remains of cities and walk through the ruins of palaces and temples; we can read texts from ancient libraries, which reveal rituals and myths, lists of omens, prayers and tax receipts, accounts of battles and the boastful inscriptions of royal achievements such as buildings, laws or military campaigns. Inevitably, our history of the ancient world is a skewed one: we know who commissioned a pyramid (and was entombed in it), but not a single name of one of the thousands who constructed it.

Whatever had preceded the advent of kingship is lost to history. One of the earliest preserved texts, the Sumerian King List (the surviving tablet is dated 2125 BCE), opens with the words, ‘After the kingship descended from heaven . . .’. The gods handed laws to the kings, who, in their own words, always ruled justly, served the gods and destroyed their enemies. Kings of course, were frequently usurped, even assassinated, but kingship always persisted. No other system ever seems to have been envisaged (even among the gods). Warfare was endemic, since it constituted a justification for kingship and the existence of standing armies; it also provided a source of wealth in booty and slaves. In Mesopotamia, as in most of the ancient Near East, cities fought each other for supremacy. The Sumerian King List describes this process as follows: ‘Erech was defeated; its kingship was carried off to Ur . . .’. The successive supremacy of Mesopotamian cities is sometimes reflected in the mythology: our text of the Babylonian Creation Epic (from the twelfth century BCE) features Marduk and his city of Babylonia; but it adapts older Sumerian epics, and in turn an Assyrian copy replaces Marduk with the Assyrian god Asshur.

Egypt was in some ways dissimilar to Mesopotamia. It was a politically unified country (theoretically, a union of two countries, Upper and Lower Egypt), not a group of city-states. Unlike the lands ‘between the rivers’, it was seldom threatened from outside, though in due course it did succumb to Assyria, Persia, Alexander and Rome. It enjoyed a stable agricultural economy, since the annual flooding of the Nile was more reliable than the flooding of the Tigris–Euphrates basin (which often inundated cities). The pharaoh reigned supreme as the son of the god Amon, the king of a large society of gods. Hence the chief religious preoccupations were the sun and the underworld; in the Egyptian cosmos, the sun sailed (how else did one travel in Egypt?) daily into the underworld and back, just as the pharaoh and at least the upper classes would pass, after their death and judgement, into that world where Osiris ruled.

Egypt and Mesopotamia formed the two ends of the ‘Fertile Crescent’ and each exerted a strong influence on the lands between. Palestine was under Egyptian control until the end of the Bronze Age (thirteenth century BCE), when some kind of crisis, possibly economic, saw a collapse of the political system. Mesopotamia, where a Semitic population had overlain the non-Semitic Sumerians in the late third millennium, gave a cultural lead to the largely Semitic peoples of Syria and Palestine. The language of Mesopotamia, Akkadian, became the literary lingua franca of the entire Fertile Crescent in the second millennium, as we know from the letters written by kings of Palestinian city-states to the Pharaoh Akhenaton in the fourteenth century BCE and found in his capital at Tell el-Amarna.

In the thirteenth century, an influx of what were called ‘Sea Peoples’, which included Philistines, settled in Palestine, having been repelled from Egypt by the Pharaoh Merneptah. These peoples, whose origins lay somewhere among the coasts or islands of the Eastern Mediterranean, quickly absorbed the indigenous culture, but the Philistine cities of Gaza, Ashkelon, Gath, Ashdod and Ekron remained powerful and politically independent for several centuries (giving, of course, their name to the land of ‘Palestine’). At this time, new territorial states also arose in Syria and Palestine, including Israel and Judah. But a new age of empire soon arrived.

Empires are a natural extension of the social processes that governed kingship: patronage, in which protection was offered by the ‘patron’ to the ‘client’ in return for services (in our own day, the best-known example of the patron is the ‘Godfather’). Chiefs and kings ruled in precisely this way, and it was by making other kings into clients that empires were constructed, by extracting loyalty in the form of tribute and political allegiance. However, as the trappings of kingship tend to expand, they require more income, and also empires consume huge amounts of wealth. City-states had tried to establish military superiority over each other for the purpose of extracting economic surplus, and this is how empires begin, with the extraction of wealth by annual subscription, often requiring a military threat or even military action. This typically gives way to more direct administration of territories as provinces (the history of the British Empire is an excellent illustration). Trading had always been an instrument of royal administration and a source of income (including imposing duties on the passage of goods). This too was more effective if directly stimulated and controlled by the ‘king of kings’.

The first great empire builders of the ancient world were the Assyrians, and they drew the map of the ancient Near East early in the first millennium. All empires face external and internal threats, more or less continually and in the end they succumb, as did Assyria late in the seventh century. To the extent that empires create any kind of political or economic system, they persist under new ownership. The Assyrians’ immediate successors, the Neo-Babylonians, took over the Assyrian Empire, though they learnt very little in doing so. (The Persians, by contrast, learnt much.)

Assyria was under-populated, landlocked and culturally dominated by Babylonia. It expanded aggressively in two waves between the tenth and seventh centuries, subduing its neighbours and driving westwards towards the Mediterranean coast where lay material wealth, manpower and trade opportunities. Its system of patronage, making vassals of the rulers of territories it wished to control, was inscribed in treaties in which the commitments of each side were made public and sealed with an oath. Such a format is clearly visible in the ‘covenant’ (treaty) of the book of Deuteronomy, where Yahweh is the patron and Israel the client. However, the Assyrians did not invent the vassal treaty: before them, the Hittites and others had used it. Patronage is an age-old mechanism.

Assyria found itself converting vassals into provinces, as it did in Israel after it put down yet another rebellion, killed the king, effected some population transfers and carved out three provinces. Judah was left, however, with a vassal king. In the ruins of the city of Ekron (Tell Miqneh) lie the remains of a very large olive oil production installation, from the mid-to-late seventh century, producing over a million litres a year. It is likely that Judah’s own production was also integrated into a larger economic system. The Ekron facility shows us how the Assyrians managed an empire, and also how Judah’s political independence was nominal.

Kingdoms, cities and empire, however, are not simply political machines; they also create and sponsor cultural activities. The ruler of Assyria in the mid-seventh century was Ashurbanipal, who could probably read and write (very unusual for a king) and who spent much of his life accumulating a library of classical Mesopotamian literature, without which we would know much less about the literature of ancient Mesopotamia than we do. His collection was assigned to different rooms according to subject matter: government, religion, science, each room having a tablet near the door that indicated the general contents of each room. Libraries were already a well-established institution of the great cities of the Near East and have been excavated at Ebla, Mari, Nuzi and Ugarit.

His cultural activities did not prevent Ashurbanipal from extending his empire, but it fell a few decades later. The Neo-Babylonian kings (of whom Nebuchadrezzar is the best known) inherited an empire that the Medes and Persians in turn overcame less than a century later, when Cyrus marched into Babylon as the ruler appointed by Marduk. The Persians were faced with a highly diverse empire, and a highly expensive one. Rule of the empire was confined to the Persian aristocratic families, while the territories were divided into satrapies and subdivided into provinces, where their inhabitants were encouraged to enjoy cultural autonomy. The satraps were mostly Persian, but governors of provinces would often be local. The Persians were not Semitic, like most of the peoples from Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine, and the religion of the rulers (from the beginning or almost) was different from what had previously been known in the Fertile Crescent: Zoroastrianism. Here was a monotheistic system (though with a dualistic aspect) which has no deification of the female but believes in a judgement of souls after death, and afterlife in heaven and hell.

We actually know more about the Persian Empire from Greek sources than Persian ones. The Persians engaged with the Greeks, first, as a major trading presence but then in a struggle with the Greek colonies of Ionia, leading to a Persian attack on Greece itself (480 BCE), and ultimately to the campaigns of Alexander of Macedon. The Greek account of that war is contained in the Histories of Herodotus (440) who also tells us about the history and customs of the people of the empire. In addition, Xenophon wrote the Anabasis, a story of the march home by Greek mercenaries who had been enlisted by a rival to Artaxerxes (another Cyrus) to try and take the throne (401–399 BCE). He also wrote a life of Cyrus the Great, the Cyropaedia.

The classical world

The political system of Greece evolved later than Mesopotamia or Egypt and urbanization did not begin until about 800 BCE. Gre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for The Blackwell Companion to the Bible and Culture

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Notes on Contributors

- Figures

- Preface to the Paperback Edition

- Introduction

- PART I: Revealing the Past

- PART II: The Nomadic Text

- PART III: The Bible and the Senses

- PART IV: Reading in Practice

- Index of Biblical References

- General Index