![]()

1

Introduction to Mindfulness and Acceptance-based Therapies for Psychosis

Joseph E. Oliver, Candice Joseph, Majella Byrne, Louise C. Johns and Eric M. J. Morris

1.1 Introduction to Psychosis

‘Psychosis’ is an umbrella term covering a range of associated symptoms, including perceptual, cognitive, emotional and behavioural disturbances. The term tends to refer to ‘positive’ symptoms of unusual beliefs (delusions), anomalous perceptual experiences (illusions and hallucinations) and disturbances of thought and language (formal thought disorder) (described in Peters et al., 2007). These are invariably accompanied by emotional difficulties such as anxiety and depression (Birchwood, 2003; Freeman & Garety, 2003; Johnstone et al., 1991). In addition, a significant proportion of people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, particularly schizophrenia, are likely to experience ‘negative’ symptoms such as avolition and anhedonia (described in Kuipers et al., 2006). The median incidence of psychotic disorders is estimated at 15.2 per 100 000, with estimates ranging between 7.7 and 43.0 per 100 000 (McGrath et al., 2004), indicating a high degree of variability in incidence across geographic regions. The reported lifetime risk remains at approximately 1% (Saha et al., 2005).

One of the diagnostic peculiarities of psychosis is that two individuals can receive the same diagnosis but have completely different sets of symptoms that have no overlap or commonality. This perhaps points to some of the complexities of the disorder, which the current accumulated evidence suggests is likely a manifold interaction between a range of genetic, biological, psychological and social factors, with probable multiple aetiological pathways (Oliver & Fearon, 2008). Furthermore, psychotic symptoms are not exclusively reported by those with a diagnosis of psychotic disorder (such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder), but also occur in varying degrees in other mental-health problems, including bipolar affective disorder, mood disorders and personality disorders (particularly borderline personality disorder (BPD)). Additionally, some authors have vigorously criticised the schizophrenia diagnosis, arguing that the associated breadth and diversity of clinical phenomenology actually represents a lack of construct validity and reliability (Bentall, 2003; Boyle, 2002).

The mere presence of psychotic symptoms, no matter how apparently bizarre they may be, is not sufficient to warrant a diagnosis. Key to a psychotic disorder is recognition that the symptoms must co-occur with significant interruption to the individual’s life. Schizophrenia is associated with significant long-term disability (Thornicroft et al., 2004; World Health Organization, 2001) and, in addition to positive and negative psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms are also strong predictors of poor quality of life in this client group (Saarni et al., 2010). For those who continue to live with distressing psychotic symptoms and emotional disturbance, advances in treatments for psychosis are of paramount importance.

Alongside the devastation that psychosis can cause to the lives of individuals and their families, there are also significant economic costs. Estimates suggest that in 2002 the direct (e.g. service charges) and indirect (e.g. unemployment) costs associated with psychotic disorders were approximately $62.7 billion in the United States (Wu et al., 2005). Similar estimates within the United Kingdom have indicated costs of approximately £4 billion (McCrone et al. 2008).

1.2 Interventions

The first line of treatment for psychosis is almost always antipsychotic medication. However, there are limitations to pharmacological treatments, including issues of compliance, intolerable side effects and poor symptomatic response to antipsychotic medication (Curson et al., 1988; Kane, 1996; Lieberman et al., 2005). These findings, in conjunction with the recognition of the importance of social and psychological factors in psychosis (Bebbington & Kuipers, 1994; Garety et al., 2001; van Os, 2004), have contributed to the development of psychological interventions for people with psychosis. Such interventions include family therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and social and cognitive rehabilitation. They are not proposed as alternatives to medication, but are used as adjunctive therapies.

1.2.1 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

The main assumption underlying CBT is that psychological difficulties are maintained by vicious cycles involving thoughts, feelings and behaviours (Beck et al., 1979). Therapy aims to break these cycles by helping people to learn more adaptive ways of thinking and coping, which leads to a reduction in distress. In the 1980s and 1990s, research on psychotic symptoms led to treatments that adapted the successful use of CBT for anxiety and depression to the more complex problems of psychosis (Fowler et al., 1995; Kingdon & Turkington, 1991). Cognitive models of psychotic symptoms (e.g. Garety et al., 2001; Morrison, 2001) have informed the development of therapeutic approaches, highlighting that it is not the unusual experiences themselves that are problematic, but the appraisal of them as external and personally significant. CBT for psychosis (CBTp) aims to increase understanding of psychosis and its symptoms, reduce distress and disability arising from psychotic symptoms, promote coping and self-regulation and reduce hopelessness and counter-negative appraisals (of self and illness) (see Johns et al., 2007 for an overview).

Evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) has shown that CBT delivered on a one-to-one basis is efficacious for individuals with psychosis, particularly those with persistent positive symptoms (Smith et al., 2010; Wykes et al., 2008; Zimmerman et al., 2005). A meta-analysis of 33 studies by Wykes et al. (2008) revealed a modest overall effect size of 0.40 for target symptoms and effect sizes ranging between 0.35 and 0.44 for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, functioning, mood and social anxiety. A recent study identified CBTp as being most effective when the full range of therapy procedures, including specific cognitive and behavioural techniques, are implemented (Dunn et al., 2011). While CBTp offers symptom improvement in some areas for a number of people, it is not a panacea.

1.2.2 Developments in CBT: Contextual Approaches

Additional developments in the field of behavioural and cognitive therapy approaches have led to the evolution of a cluster of therapies termed ‘contextual CBTs’ (Hayes et al., 2011). This evolution has been in response to several anomalies present within the CBT model, including debate about whether cognitive change/restructuring is actually the necessary component of therapy (Hayes, 2004; Longmore & Worrell, 2007). While not ignoring the importance of cognition, contextual approaches emphasise the historical and situational context an organism is situated within as a means for focusing upon central processes to be targeted to effect behavioural change. Critically, contextual approaches deemphasise the importance of changing the content and frequency of cognition, moving instead towards the use of acceptance and mindfulness procedures to alter the context in which these experiences occur, thereby increasing behavioural flexibility.

A number of approaches fall under the umbrella of contextual CBT, including dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) (Linehan, 1987), functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP) (Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Teasdale et al., 1995), integrative behavioural couples therapy (IBCT) (Jacobson & Christensen, 1996), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., 1999), metacognitive therapy (MCT) (Wells, 2000) and person-based cognitive therapy (PBCT) for psychosis (Chadwick, 2006). These therapies include components such as mindfulness, experience with the present moment, acceptance, values and greater emphasis on the therapeutic relationship. While they may incorporate more traditional behavioural and cognitive techniques, they tend to be more experiential in nature and involve second-order strategies of change as well as first-order ones. Within these therapies, ACT, PBCT and mindfulness groups have mostly been implemented in the psychological treatment of psychosis.

1.2.3 Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

ACT is a modern behavioural approach that incorporates acceptance and mindfulness to help people disentangle from difficult thoughts and feelings in order to facilitate engagement in behavioural patterns that are guided by personal values. It has firm roots in behavioural traditions and is underpinned by a behavioural analytic account of language: relational frame theory (RFT) (Blackledge et al., 2009). Broadly, the ACT stance focuses on changing one’s relationship to internal experiences (thoughts, feelings) rather than altering the form or frequency of these experiences (Hayes et al., 1999). The approach is transdiagnostic and uses the same theoretical model to formulate and target common processes underlying a wide range of symptomatically diverse problems (such as depression, BPD and diabetes).

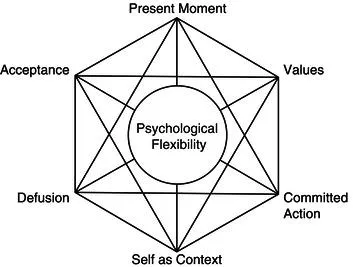

ACT’s six core theoretical processes are set out visually in a hexagonal shape (known colloquially as the ‘hexaflex’; see Figure 1.1) and move in synchrony towards increasing psychological flexibility or ‘the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behaviour when doing so serves valued ends’ (Hayes et al., 2006, p. 7). These processes are highly interrelated and, although represented as distinct entities in the model, share considerable overlap. More recently, the processes have been clustered into three broader sets of response styles: open, aware and active (Hayes et al., 2011) (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Central ACT processes (adapted from Luoma et al., 2007)

|

| Open | |

| Acceptance | The active and aware embrace of private events that are occasioned by our history, without unnecessary attempts to change their frequency or form, especially when doing so would cause psychological harm. |

| Defusion | The process of creating nonliteral contexts in which language can be seen as an active, ongoing relational process that is historical in nature and present in the current context. |

| Aware | |

| Self as Context | A continuous and secure ‘I’ from which events are experienced, but which is also distinct from those events. |

| Present Moment | Ongoing, nonjudgmental contact with psychological and environmental events as they occur. |

| Active | |

| Values | Verbally constructed, global, desired and chosen life directions. |

| Committed Action | Step-by-step process of acting to create a whole life, a life of integrity, true to one’s deepest wishes and longings. |

1.2.3.1 Open

The processes of acceptance and defusion work synergistically to build the broader skill...