eBook - ePub

Human Factors in the Health Care Setting

A Pocket Guide for Clinical Instructors

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Factors in the Health Care Setting

A Pocket Guide for Clinical Instructors

About this book

Human factors relates to the interaction of humans and technical systems. Human factors engineering analyzes tasks, considering the components in relation to a number of factors focusing particularly on human interactions and the interface between people working within systems. This book will help instructors teach the topic of human factors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Factors in the Health Care Setting by Peter-Marc Fortune, Mike Davis, Jacky Hanson, Barabara Phillips, Peter-Marc Fortune,Mike Davis,Jacky Hanson,Barabara Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Human Factors in Medicine

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter you should be able to demonstrate an understanding of:

- the historical background to patient safety

- the concept of clinical error

- the range of human factors

- the structure and aims of this text

Introduction and Aims

The aim of this text is to help the reader improve safety in their own practice, in the teams in which they function and in their organisation. This will be achieved by understanding the human factors that contribute to error and exploring ways to prevent, circumvent or minimise these factors by developing awareness and skills.

At the beginning, it is important to state that almost all people in the healthcare professions come to work to do a good job to the best of their ability, not to make a mistake which leads to a clinical error. This book aims to provide healthcare workers with an understanding of the human factors behind clinical error, thus improving their ability to do a good job.

The Department of Health within the UK government have recently highlighted patient safety as a major issue. Many within healthcare will be aware that patient safety has been an issue throughout medical history.

Patient safety is defined as ‘the freedom from accidental injury due to medical care or from medical error’ (Kohn et al. 1999). Medical error, in this book, will be reworded as clinical error – meaning any error that has occurred in the clinical treatment of a patient. This could be caused by anyone involved in clinical care of that patient. Frequently, papers on errors talk about adverse events which are defined as errors from any cause; these may or may not be preventable. An error is any mistake that has occurred; they are specifically defined as clinical (technical) or human (non-technical).

Background Concepts

Historical Background of Patient Safety

There has been an awareness of clinical error since Hippocrates’ direction to ‘abstain from harm or wronging any man’. Prior to 1990, however, there was little in the way of literature on clinical error, and initiatives to improve quality of healthcare were sporadic (Vincent 2010). Early improvements to patient safety have been in discoveries of technical skills and systems, with the first examples coming from Semmelweiss (Jarvis 1994), whose published work in 1857 discovered that the introduction of hand disinfection reduced the spread of puerperal fever, and hence mortality. It is interesting that history has repeated itself with the handwashing audits of today, thus a discovery from the 19th century had to be re-emphasised to reduce the spread of hospital-acquired infections. Lister discovered the original concept of the use of antiseptics, but it took until the end of the 19th century for antiseptic techniques to be fully established.

Codman, an American surgeon in the early 1900s, was the first to categorise errors in surgery, culminating in the minimum standards used in the United States until 1952 (Sharpe & Faden 1998). In 1928, maternal morbidity and mortality was investigated in the UK, with national reports produced sporadically until 1952 when the ‘Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths’ was set up, which continues today (CMACE 2011).

The first documentation of adverse events was by Schimmel (1964). He looked at adverse events, excluding clinician error, and found that 20% of patients had at least one adverse event, pointing out that greater attention was needed to look at clinical risk. His results are similar to those shown in Table 1.1 for the last 20 years. Ivan Illich in 1977 stated that the medical profession had become ‘a threat to health’. This was a challenging statement that should alert us to the need to explore patient safety issues and lead to an appreciation of the contribution that human factors make to clinical error.

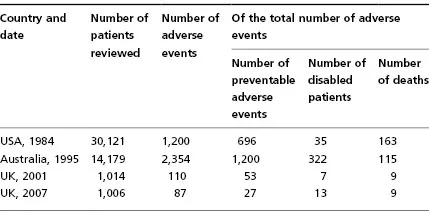

Table 1.1 Adverse event incidence in various studies across the world

Data from Brennan et al. (1991), Wilson et al. (1995), Vincent et al. (2001) and Sari et al. (2007).

Background to Clinical Error

The United States was the first country to investigate clinical error systematically. In 1984, Brennan et al. looked at 30,121 admissions to New York hospitals and found 1,200 (4%) adverse events overall (Table 1.1). Adverse events were deemed preventable in 58%; 3% of adverse events led to permanent disability and 14% led to death. Extrapolating these figures and others (including the Utah and Colorado figures) to the whole of the USA, there may be between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans dying in hospital per year due to clinical error, at an approximate cost of $17–29 billion (Kohn et al. 1999). This exceeds the mortality rate for breast cancer and severe trauma in the USA.

In Australia, Wilson et al. (1995) reviewed 14,179 admissions in New South Wales hospitals and showed an adverse event occurring in 17% of admissions, of which 51% were preventable, 14% caused permanent disability and 5% resulted in death. When extrapolated to all Australian admissions, this equates to 18,000 deaths per year at an approximate cost of 4.7 billion Australian dollars.

In 2001 in the UK, Vincent et al. looked at 1,014 hospital records retrospectively and showed that adverse events had occurred in 11% of patients, 48% of which were from preventable clinical error, producing 6% permanent disability and 8% deaths. This was extrapolated to calculate the cost of extra bed days alone, which was approximately £1 billion. More recently, Sari et al. reviewed case notes retrospectively and found 9% of admissions had at least one adverse event, of which 31% were preventable, with 15% of clinical errors producing disability for greater than 6 months and 10% contributing to deaths. They also noted an increased mean length of stay of 8 days associated with error. The report showed that there had been little improvement from 2001 to 2007 (Sari et al. 2007).

From the 1980s onwards there was an increase in literature regarding clinical error, and the National Health Service (NHS) started to highlight quality of care, developing systems to improve patient care and safety. McIntyre and Popper (1983) published ‘The critical attitude in medicine: the need for a new ethics’, encouraging doctors to look for errors and to learn from mistakes. Anaesthetics was the first specialty to start to look at error, notably in systems involving equipment, led by Cooper in 1984. This developed the concept of looking at both psychological and environmental causes, which was furthered during the 1990s, in both anaesthetics and obstetrics, in the USA (Cooper 1994). Gaba and his colleagues advanced this idea, developing crisis resource management in anaesthesiology which provided structure and advocated utilising simulation to practise untoward events. He wrote: ‘No industry, in which human life depends on the skilled performance of responsible operators, has waited for unequivocal proof of the benefits of simulation before embracing it,’ (Gaba et al. 1994).

Leape took this a step further and broadened the concept to include all aspects of medical and nursing care. He discussed the common problem of ‘blame culture’, which exists in health services, and argued that this had to change. He further maintained that the change would only occur if the medical fraternity accepted that psychology and human factors play a big role in clinical error (Leape 1994). To this end, the UK, USA and other developed countries have made concerns regarding patient safety public. To Err is Human was published by the Institute of Medicine in the USA (Kohn et al. 1999), and An Organisation with a Memory: Learning from Adverse Events in the NHS (Department of Health 2000) was published in the UK. Both of these documents encouraged learning from other high-risk industries, for example aviation, nuclear and carbon fuels, which have well-developed systems for training and learning from error within their environment.

The House of Commons Health Committee Report on Patient Safety in 2009 highlighted 850,000 adverse events reported in the NHS in England, with deaths in 3,500 patients. Concomitant to the increasing statistical evidence for clinical error, there has been growing awareness that clinical error is not only due to error in knowledge or skill (i.e. technical error) but also involves non-technical error, otherwise known as human factors.

The ‘Patient Safety First’ initiative1 describes the process of developing a positive safety culture by providing an open and just environment where staff are comfortable discussing safety issues, and are treated fairly if they are involved in an incident. In these circumstances, the development of a reporting culture does not imply blame. The initiative argues that there needs to be a culture open to learning and information sharing, thus enabling all to learn from errors and prevent further episodes.

Human Factors

The Elaine Bromiley case was highlighted in a ‘Patient Safety First’ document (Carthey et al. 2009). She was a fit, young woman who went for a routine ENT operation and the anaesthetist experienced the ‘can’t intubate, can’t ventilate’ situation. This developed into a catalogue of errors as attempts to intubate her failed despite emergency equipment being brought in by the nurses, and, tragically, because of a chain of human errors, she never regained consciousness. Elaine Bromiley was married to an airline pilot who could not believe, during the investigation of his wife’s death, that medical staff had no training in human factors. He has subsequently become the founder of the Clinical Human Factors Group and was involved in writing the ‘Patient Safety First’ document. The Department of Health film made with the help of Elaine’s husband, Martin, is available at http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/general/human_factors.html. The film is a valuable and powerful introduction to the subject.

What Are Human Factors?

Human factors are systems, behaviours or actions that modify human performance. They can be attributed to the individual, a team of individuals or the way these individuals interact with the working environment. Human factors operate on two levels.

Level 1: How Humans Work in a Specified System or Environment (Includes Ergonomics)

Human factors and ergonomics is a discipline in itself and looks at how people interact with systems. It combines looking at human capabilities and the design of systems to maximise safety, performance and ability to work together in harmony. This specialist field was first developed in the Second World War with the development of aviation medicine and psychology. Since then, technology has advanced significantly and so has the field of human factors and ergonomics.2 It is now multidisciplinary, including psychologists, engine...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Working group

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Contact details and further information

- CHAPTER 1 Introduction to human factors in medicine

- CHAPTER 2 Human cognition and error

- CHAPTER 3 Situation awareness

- CHAPTER 4 Leadership and teamworking

- CHAPTER 5 Personality and behaviour

- CHAPTER 6 Communication and assertiveness

- CHAPTER 7 Decision making

- CHAPTER 8 Fatigue and stress

- CHAPTER 9 Key elements in communication: briefing and debriefing

- CHAPTER 10 Organisational culture

- CHAPTER 11 Guidelines, checklists and protocols

- Anthology

- Index