![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Design Engagement

Reflect for a moment on when you first decided to learn more about design. Did this interest begin at an early age or did it surface after taking an introductory design class? Or did the calling come well into adulthood when at a crossroad you considered a new career path? After that interest began taking root, did you start observing the world around you in different ways? Did this coincide with looking more critically at interiors and considering alternative ways of designing spaces? Did your curiosity lead to questions? “I wonder what that is made of?” “How was that built?” Did a specific interior designer or design instructor inspire you to come into the field? While everyone’s story is unique, someone or something ignited your interest in the field. And this new focus, in turn, motivated new learning—and you began developing further than you thought possible.

A Starting Point

The starting point for learning anything begins with a question. Curiosity leads to questions. A search for information and a way to gain skills begins. Such a starting point falls anywhere along a continuum of knowledge, from a beginner’s understanding to advanced expertise. Even though an initial interest might be personal, as knowledge grows, so does the potential for creative thinking and design contributions. A comprehensive understanding of design allows development to progress on solid footing.

This book begins with an interest in interior design. It is our starting point. You, the reader, and we, the authors, must share an orientation to what design means and reach a common understanding. The central premise of this book is that in today’s world memorable design goes beyond form and function. Having a clear understanding of design and its purpose in human existence sets the stage for later discussion on the six markers of memorable design, engaged experience, and a role for stories.

We aspire to design in ways that are supremely satisfying and innovative. While creating designs with similar materials, similar elements, and similar needs, the manner in which individuals know and combine these components differs, creating unique interior spaces. The process and its results, in turn, offer discovery, enjoyment, and a sense of heightened belonging in everyday life. Such knowing, doing, and experiencing of design have a variety of meanings that eventually impact the quality of human life.

Design has long been described as product—as noun or an object. From this view, we speak about form and space, or style. We notice design materials and the uniqueness of substance and arrangement. Design is also a process—a verb, an ordering principle guiding spatial arrangement. From this standpoint, we notice how to organize and think about how designers create within the interior. Within this process, we also recognize not only the designer but also the clients, and those who occupy the interiors. Process encompasses design thinking and creative problem solving that guide decision making and action. Design occurs in many professions, such as industrial and product design, engineering design, urban and regional planning, landscape architecture, architecture, interior design, environmental graphic design, design communications, set design, and textile design. Yet designers, educators, clients, and users also view design as an experience. According to Yi-Fu Tuan,1 the definition of experience engages many modes—visual, symbolic, behavioral, social, and cultural—from which to come to know reality. Design experience is multimodal and reflects the force of the whole, the gestalt, the nondiscursive spirit of design. The physical, intellectual and spiritual mingle as parts of design experience.

To define design as experience shifts the focus from a purely physical entity to human meanings of interiors or places. Design in this sense is relational. It is about connections among elements, settings, roles, and people. Design experience presents a deeper and more expansive understanding of design as a whole. In other words, we ask, “What is being experienced? How is it experienced?” “What does the experience mean to designers, to clients, to users?” “How does design experience transform human living?”

To become truly knowledgeable about design experience requires an understanding of both people and place. In turn a person filters design knowledge, theory, and skills to arrive at a more comprehensive knowing of interiors. Having knowledge about environmental psychology differs from knowing and applying environmental psychology within interior design. Having knowledge of color theory differs from knowing and applying color to transform interior spaces. It is this latter integration of knowing and doing that we seek to expand.

Bill Stumpf, a well-known industrial designer of the late twentieth century, wrote one of the most powerful passages about design:

This observation by Stumpf captures the humaneness of design work, the physical materiality and the thinking involved. He cites objects, places, or paths to which humans bring order. He speaks to interconnected design thinking, making, and experience—as both artistic and scientific. He beautifully captures intents of design as connections to human realities of work, fun, extending human capacities, and making living meaningful. Design links humans in their environments and to larger meanings of living life.

Specifically, the framework for this book rests on the following assumptions, which also should be considered when designing interiors:

- While design crosses different fields, we define the interior as the architectural interior and its elements.

- Knowledge about interior design is interdisciplinary in nature and rooted in art, humanities, social sciences, and business.

- Design of interiors involves intellectual information and analysis combined with creative thinking, making, and innovation. It is holistic in its way of being in the world.

- Design of interiors adds meaning to human life by impacting built and natural environments and the quality of the human experience.

- Designers and their clients benefit from investing in design processes, design products, places, and paths that result in meaningful engagement.

- Interior design, as a profession, attracts individuals who want to see their knowledge, skill, and talents at work in a real-life situation.

These designers:

- Make new visual and experiential forms

- Design for and serve clients and users

- Have the ability to observe, interpret, and apply cultural, historical, social, and technological perspectives in their work3

Such assumptions reinforce design as a whole, the gestalt—the more than a sum of parts. People, as individuals, groups, societies, or cultures show behaviors and values that connect to spaces and the objects within them. When we study these connections with care, a fuller appreciation of designing interiors emerges. Society benefits as well. Yet to study such a complex topic, it is helpful to know the key features that form fundamental connections and act across time, people, and settings.

Design Engagement Framework

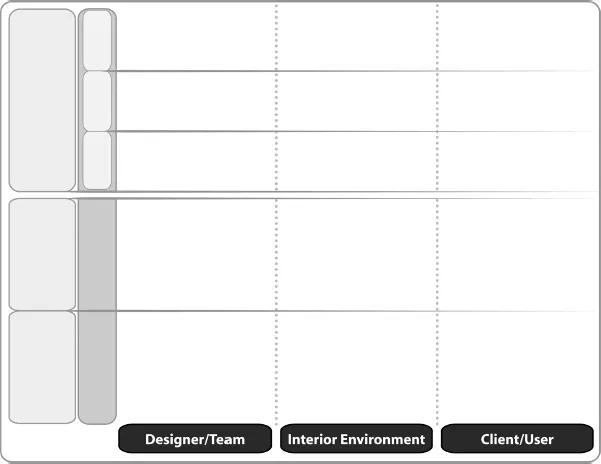

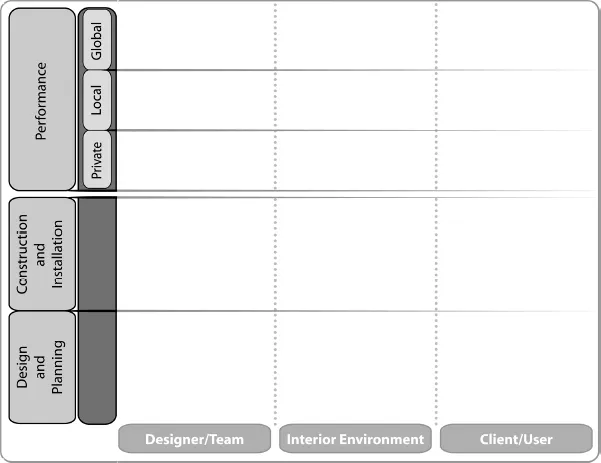

In recognition of the issues just discussed, we developed the Design Engagement Framework to acknowledge a holistic approach to the discipline. The horizontal direction of the framework (Figure 1-1) underscores three key features: designer or design team, interior environment and its elements, and client and users. Each is a stakeholder: individuals and an environment at stake. Designers take roles of observer, interpreter, planner, translator, communicator, and creator of a place. Clients and users are perceivers and residents to which the place must belong and for which the design has a various meanings.

The core environmental setting—the interior design—maintains a powerful role. It calls forth and gives energy through a common purpose when two or more of these individuals come together. The interior and its design become their link, their uniting force. Designer, client, and users, with their distinctive roles, help advance ideas and contribute to a best resolution for their common interests in the interior setting and its purpose. Finally, the built design stands on its own for others to experience, to assess or recreate. The built design communicates in a different voice, a nondiscursive voice. Yet, it realizes tangible and intangible judgments and tastes that are now concrete reality. Often, the space reflects the designer’s and client’s priorities, meanings, as well as their ability to draw connections and a best fit between people and their spaces.

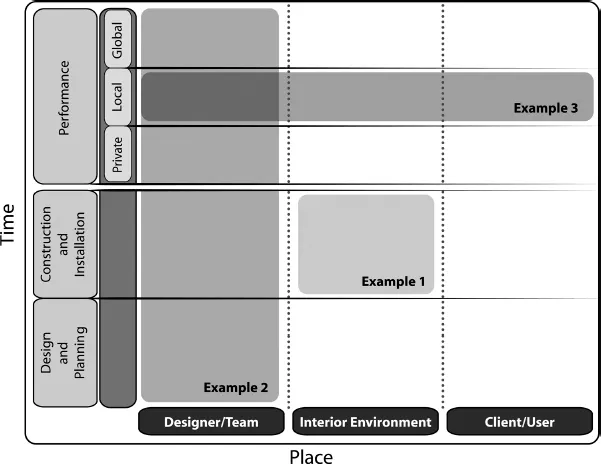

Moving vertically, the framework considers time features (Figure 1-2). Time cycles throughout projects given different filters, as ideas become physical realities. Time comes into play when thinking, researching, and planning. Design requires construction-installation time. Likewise, time emerges as a feature when presentation and design performance engage stakeholders. Time at this stage may be private and/or public where local and global represent platforms of performance. A private time for designer, firm, setting, or client reflects occasions when one might document and assess work in one’s own way. Local and global times reflect level, type, or scope of design works. If one considers only the designer and team column, local and global help assess where recognition of design skill, knowledge, or leadership is realized as an example. If one considers the interior settings column, finished designs stand on their own with the characteristics of the interior, personality of interior, and a site-specific location. They become a socio-cultural artifact at a level that provides a standard. They can equally reflect a historical design that has local presence and meaning but later brings new exploration to the world stage. If one explores the client or user column, one might ask how a client contributes to or markets the interior as an asset of local or global profile.

Articulating the role of time in design responds to the changing nature of design. Interior design is never static. The Design Engagement Framework (Figure 1-3) allows practiced designers as well as beginning students to see design as relational and encourages the exploration of connections from the framework. They may also see a design feature singularly; for instance in Example 1, the focus is on the interior setting during construction where a new skill or material is studied. Another example is client/user participation at a time of planning. With greater complexity, relational issues and questions might emerge when considering vertical time frames and their interactivity. For instance (Example 2), what is the fluidity and constancy of a design team’s membership from design planning through design construction to design completion? And what membership is constant? What members come and go? What are the costs? How efficient and effective is the make up of the team? Or the same progression of movement could be explored from what the interior itself reveals as a design historian or anthropologist might develop.

Conversely, the framework allows discernment of a single time phase, such as “local time presence and market” across multiple stakeholders of design firm, interior place, and client-users (Example 3). If marketing is being developed, what might be shared about firm, place, and client in the context of the community? What does each bring? What is their impact on one other? How does the project benefit the local community? Again, we think the framework helps advance seeing knowledge and skill through a relational mindset.

Design Engagement as Relational Explained Further

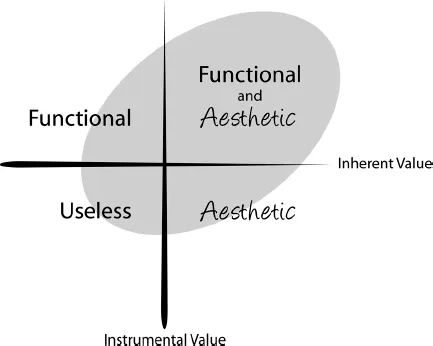

The Design Engagement Framework draws from the early work of V. T. Boyd.4 A design historian, Boyd and her colleague Timothy Allen examined ways objects are valued. Their model (Figure 1-4) presents the intersecting continuums of the object’s perceived inherent (inner) value and instrumental (external) value.

For example, a card from a friend may have a high inherent value but a low instrumental one. Each of the model’s quadrants identifies one of the following: (1) objects valued for high aesthetic quality and lower functionality (a beautiful sculpture), (2) objects valued for high inherent and functional value (a sexy and comfortable chair), (3) objects valued for high functional use with lower aesthetics (a tool), and (4) objects viewed as having little functionality or aesthetic value (a grocery bag too thin to hold purchases). The model recognizes the relationship among the designer, object, and perceiver, as well as the values we place on objects. This model goes beyond understanding reactions to designs in terms of either “likes” or “dislikes,” yet the study also documents that such responses offer early leads to final value positions.

Boyd’s model inspired an early version of the Design Engagement Framework, which considered social issues, valuing, and other influences when teaching, learning and doing design projects in education.5 It focuses the study of student development of design thinking and skills during phases of preparation, production, and presentation as well as performance. The work also acknowledged a creative and evaluative pos...