- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Supply Chain Performance and Evaluation Models

About this book

This book presents the different models of supply chain performance evaluation for global supply chains. It describes why it is necessary to evaluate global performance both to assess the contribution of the supply chain to achieve the goals of creating value throughout the chain and also to meet customer requirements in terms of time, responsiveness and reliability.

The author provides an understanding of how evaluation models are chosen according to criteria including the level of maturity of the organization, the level of decision-making and the level of value creation desired.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Quality Control in Engineering1

Supply Chain Management Modeling

1.1. Supply chain management

Historically, the management of flows was mainly concerned with internal company processes, aiming to optimize material, information and financial flows. The concept of logistics defined this early stage in the development of the management of flows [COL 96]. With logistics management, the purchasing, production and distribution were not considered separately; they were managed as part of an overall view of flows within the company.

In 1986, the Council of Logistics Management (CLM), which is now the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), defined logistics management as “The process of planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient, cost effective flow and storage of raw materials, in-process inventory, finished good, and related information flow from point-of-origin to point-of-consumption for the purpose of conforming to customer requirements” [COO 97].

The consideration of distribution points and production plants within the management of flows led to the evolution of the concept of logistics from a company-centered approach toward a more global logistics approach [COL 96].

This marked a turning point in supply chain management: from this time onward, all the partners in the chain were taken into account. They were no longer seen as being independent of each other, but rather as needing to learn to coordinate and synchronize their activities.

Study of the supply chain management has come into being as a result of this need to coordinate the activities of various companies and their flows, from the suppliers’ suppliers to the end customer.

It aims to achieve coherence between the various actors in the chain, even where their end goals do not match.

Forrester has clearly illustrated the intraorganizational nature of logistics: “Management is on the verge of a major breakthrough in understanding how industrial company success depends on the interactions between the flows of information, materials, money, manpower, and capital equipment. The way these five flow systems interlock to amplify one another and to cause change and fluctuation will form the basis for anticipating the effects of decisions, policies, organizational forms, and investment choices.” [FOR 61] cited in [MEN 01b].

During the 1990s, supply chain management was seen as being a systemic approach that viewed the chain as one unique whole rather than a set of disparate elements working toward their own individual goals. [MEN 01b] provides a pertinent overview of the different definitions of supply chain management.

“The objective of managing the supply chain is to synchronize the requirements of the customer with the flow of materials from suppliers in order to effect a balance between what are often seen as conflicting goals of high customer service, low inventory management, and low unit cost.” [STE 89].

Supply chain strategic management involves “… two or more firms in a supply chain entering into a long-term agreement; … the development of trust and commitment to the relationship; … the integration of logistics activities involving the sharing of demand and sales data; … the potential for a shift in the locus of control of the logistics process” [LA 94].

Supply chain management is “an integrative philosophy to manage the total flow of a distribution channel from supplier to the ultimate user” [COO 97].

Supply chain management is a concept, “whose primary objective is to integrate and manage the sourcing, flow, and control of materials using a total systems perspective across multiple functions and multiple tiers of suppliers” [MON 98].

Supply chain management is the integration of key business processes from end user through to original suppliers that provides products, services and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders [LAM 00b].

By definition, supply chain management requires companies to [MEN 01b]:

– extend the integration of behaviors, to customers and suppliers;

– mutually share information between the partners of a chain;

– mutually share risks and rewards, while creating a competitive advantage;

– cooperate with their partners, conducting joint operations within the context of close relationships;

– share goals with their partners, serving customers;

– integrate processes, from purchasing to distribution, including manufacturing.

Where companies need to share and integrate processes, this of course implies coplanning, sharing of profits and risks, systematic exchange of information and building bridges between the cultures of the companies involved. To achieve a level of balance between the actors, a relationship needs to become established over a relatively long period [EST 98b]. The initiatives required combine strategic and tactical modifications; successful achievement of these is attained by following three essential stages:

– intraorganizational integration: design, purchasing, production, distribution and sales;

– interorganizational integration with the company’s partners: suppliers, suppliers of suppliers, customers and customers of customers;

– the development of a flexible network of companies, ensuring a significant degree of responsiveness to the market [EST 98b].

As a result, companies that design value-creating supply chain organizations have generally created common processes with their customers. These companies define jointly shared processes that involve several actors. For example, for Vendor-Managed Inventory (VMI) processes , the actors codefine the procurement process, the inventory levels and the information systems suited to the aims and constraints of each of them. The goal of Collaborative Planning Forecasting (CPFR) is to develop a process of sharing forecasts between the actors in the chain. The collective development of processes by the actors in the chain guarantees perfect synchronization and also mutual exchange of information and/or resources [MEN 01b, EST 98a].

Companies may meet with certain difficulties when creating common processes; these have been highlighted by Balmes: “the length of processes and the disparity in management are such that it is difficult to ensure that the implemented process is sufficiently reactive when faced with fluctuations in demand” [BAL 00b]. It is not easy to achieve the involvement of every actor in this dynamics of synchronization and adding value. There are many limiting factors for each actor in the chain: organizations may be quite different from each other, and they may also have different supply chain management maturity levels. There are also strong internal limiting factors within each company, for example, the powers of commercial and purchasing functions do not favor the sharing of resources between each actor in the chain. Differences in economic scale between the companies involved in the chain may also hinder the creation of frameworks for reciprocity and mutual exchange. Technical limiting factors linked to the heterogeneity of information exchanged or of different management tools mean that common systems for exchange will need to be put in place.

On the plus side, once common processes have been developed, then it is possible to identify and counteract delays in information transmission, activities that do not add value, and any local deoptimizations that may hinder progress.

This broad global vision of the whole chain would seem to be an important factor in success, in that it can enable the improvement of performance over the entire organization in a network of companies, including through better sharing of resources (stock, transport, warehousing, etc.), more rapid response to customers and creating the dynamics for common design of products and services.

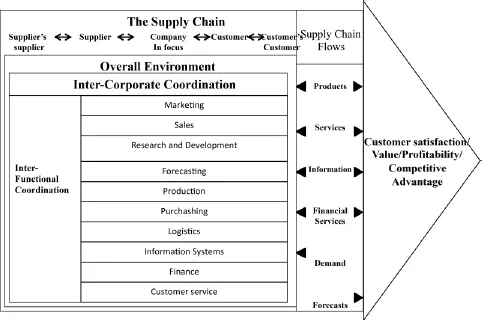

Supply chain management is an interorganizational approach, and refers to an extended company or network of companies (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. An interorganizational approach [MEN 01b]

When these multiple aspects are combined, supply chain management can be defined as the systemic and strategic coordination of classic operational functions within a company and between partners within the chain, with a long-term view to improving performance for each company and for the chain as a whole [MEN 01b].

Through all these definitions, it is apparent that the supply chain is, in fact, a set of subsystems that interact with each other. To make further progress with analysis and development, it is important to know how to model a supply chain, so that a conceptual reference framewor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Supply Chain Management Modeling

- 2 Value Creation and Supply Chain Performance

- 3 Help in Choosing Supply Chain Performance Evaluation Models

- 4 Performance Evaluation Model for Value Creation

- 5 Case Study

- Conclusion

- Appendix: List of Companies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Supply Chain Performance and Evaluation Models by Dominique Estampe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Quality Control in Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.