![]()

CHAPTER 1

Essential simulation in clinical education

Judy McKimm1 and Kirsty Forrest2

1Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 2Australian School of Advanced Medicine, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

‘The use of patient simulation in all its forms is widespread in clinical education with the key aims of improving learners' competence and confidence, improving patient safety and reducing errors. An understanding of the benefits, range of activities that can be used and limitations of simulation will help clinical teachers improve the student and trainee learning experience.’ [1]

Overview

The use of simulation for the training of healthcare professionals is becoming more and more popular. The drivers of improved patient safety and communication have led to a significant investment in the expansion of facilities and equipment across Western healthcare organizations. For example, Royal Colleges in the UK are including mandatory training using simulation within their curricula and politicians have also jumped on to the bandwagon extolling the virtues of simulation training. The use of simulation in training is becoming synonymous with effective learning and safer care for patients and is fast becoming a panacea for all the perceived ills of teaching and training. However, simulation is not a substitute for health professionals learning with and from real patients in real clinical contexts. As Gaba reminds us:

Other authors [3,4,5] note that we must take care in case the seductive powers of simulation lead to dependency, become self-referential and produce a ‘new reality’. Simulation must not become an end in itself, disconnected from professional practice.

Ongoing and outstanding discussions include the following questions: What do participants learn from simulation? How are they expected to learn? How will the knowledge and skills be transferred to clinical practice? Will general or specific aspects of performance be transferred? Do our current methods and techniques make this transfer possible? When in a clinician's training should simulation be used? How should simulation be introduced into the curriculum? When should the team be trained as opposed to the individual? Can simulation impact on patient safety? Can and should we look for a return on investment when talking about simulation education?

This book will provide the reader with evidence around these questions and much more. The contents of the chapters build from the broader themes of history, best practice and pedagogy through to the practical aspects of how to teach and train with simulation and ends with examples and possible future developments. However each chapter can stand alone for those who wish to explore a single topic. Each is written by authors who are highly experienced in the development of simulation-based education. Our thoughts on and synopses of the various chapters follow.

History

Simulation in medical training has a long history, which started with the use of very basic models to enable learners to practice skills and techniques (e.g. in obstetrics). In spite of this early start, medical simulators did not gain widespread use in the following centuries, principally for reasons of cost and a reluctance to adopt new teaching methods. With advances in materials and computer sciences, a wide range of modalities have developed including virtual reality and high-fidelity manikins, often located in dedicated simulation centres. Chapter 2 describes these developments in detail, reminding us that the combination of increased awareness of patient safety, improved technology and increased pressures on educators have promoted simulation as an option to traditional clinical skills teaching. The chapter also defines and describes a classification for stimulation. Although a wide range of simulation activities exist, these are still often linked with specific medical specialities rather than ‘centrally’ managed or resourced. How simulation can best be supported in low-income countries, where the need is great but resources are not always available, is an issue still to be addressed. The impact of simulation on patient safety and health care improvements is still relatively under-researched although an evidence base is growing.

Evidence

There is widespread agreement, supported by robust research, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, on what makes for effective simulation. This theme is further explored in Chapter 3, which considers the evidence base underpinning the widespread use of simulation-based training in undergraduate and postgraduate contexts, general and specialty-based curricula, and clinical and non-clinical settings. Simulation supports the acquisition of procedural, technical skills through repetitive, deliberate practice with feedback, and also supports the acquisition of non-technical skills, such as communication, leadership and team working. The evidence base for the former is more extensive and robust than for the latter, which has been identified as an area for further research. The value of embedding or integrating simulation within curricula or training programmes is highlighted, as is the benefit of a programmatic, interval-based approach to simulation. In addition, workplace-based simulation for established multiprofessional teams (when supported by the institution's leaders) is seen as effective way of embedding sustainable changes in practice.

Teaching, learning and assessment

Simulation is no different from many other forms of education and training: instructors or facilitators need to be skilled and knowledgeable about educational theory and how this relates to their teaching practice. As with any educational intervention, activities need to be designed to enable learners to achieve defined learning outcomes and meeting their own learning needs. However, simulation offers particular challenges to both facilitators and participants: it requires some suspension of disbelief; it may feel threatening, challenging and unsafe (particularly for experienced health professionals); and it requires skills in giving feedback, both ‘in the moment’ and through more structured debriefings. Chapter 4 considers some of the most relevant learning theories and educational strategies that help to provide effective training and overcome some of the inherent barriers to learning through simulation.

Providing high-quality educational experiences is vital if learners are to engage in simulation with all its challenges; however, assessment drives much of learning, and simulation has a huge role to play in ensuring that health professionals are fit, safe and competent to practise. In Chapter 5, the authors consider the important elements which contribute towards effective assessment of both technical and non-technical skills at all stages of education and training. As with any assessments, those using simulation should possess the attributes of reliability, validity, feasibility, cost-effectiveness, acceptability and educational impact. Assessments need to be integrated within the curriculum and within an overall assessment scheme which utilizes a range of methods. Simulation can provide opportunities for both formative (developmental) and summative (contributing to grade or score) assessments, although appropriate levels of fidelity and realism need to be selected based on the specific context. Well-designed simulation provides excellent opportunities for learners to receive timely and specific feedback from educators and real, virtual and simulated patients and so helps develop and hone clinical and communication skills. Simulation also enables those involved in assessment to consistently and reliably assess clinical performance by using increasingly sophisticated technology such as haptic trainers which incorporate internal metrics and can measure fine motor skills and give in the moment feedback, or combinations of simulations (such as simulated patients and part task trainers) which can assess complex clinical activities or team working.

A large number of checklists and global rating scales have been developed, tested and validated in various settings which give rise to both opportunities and challenges for educators. Chapter 5 describes some of the most widely used instruments. The ability to measure performance more consistently and reliably provides assurances for patients and the public that healthcare professionals are safe to practice. However, the more reliable simulated assessments become, the possibilities of using such assessments in selection, relicensing and performance management increase. For such assessments, and also for high-stakes ‘routine’ assessments, educators must be satisfied that the assessment instruments selected are appropriate and validated, that the personnel and equipment involved and scenarios chosen are appropriate and that all those involved in delivering the assessment (including standard setting, development of checklists, marking and giving feedback) are suitably trained.

The people

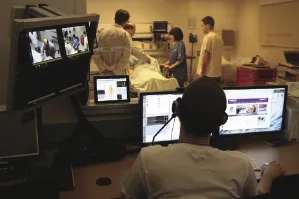

Although the range and potential of simulation equipment and computer-based technologies seems almost infinite, without the continued involvement of trained, enthusiastic and skilled people, simulation education will not flourish and grow. Chapter 6 considers the recruitment, education, training and professional development of two of the main groups involved in simulation-based education: the educators or faculty, and simulated (or standardized) patients (SPs). As with any type of education, simulation facilitators (trainers, instructors or educators) need to be trained to teach, assess, give feedback and evaluate the effect of the education alongside other teachers on healthcare programmes. As a learning modality, simulation has some unique features in which teachers require development so that they can provide high quality educational experiences, such as using technical equipment and computers and working with simulated, real and virtual patients (Figure 1.1).

The challenging nature of some simulation encounters also requires educators to be explicit about and adhere to high professional standards and values so as to maintain a safe atmosphere which encourages learning. Educators also need to be able to adopt a range of styles, such as an instructing style for novices learning a technical skill or a coaching or facilitative style for an expert group, and be proficient in techniques such as giving feedback and the debrief. Educators must also be credible, whether they are clinically qualified or not; this may mean acquiring new skills or knowledge or team teaching with clinical colleagues. In common with many areas of practice, professional standards of educators are now being widely adopted alongside increasing regulation and quality assurance. Educators therefore need to be aware of these changes and prepared to take a lifelong learning approach to their own development.

SPs have been widely used in both the teaching and assessment of health professionals and provide a valuable adjunct to involving both real and virtual patients. SP interaction with learners can vary from fairly minimal interaction with limited responses to a highly standardized and scripted encounter, in which the SP might have a lot of flexibility in how they respond to the learner. The role of SPs in providing timely and accurate feedback from the ‘patient's perspective’ is one of the key advantages of involving SPs. Many SPs are also trained as educators who can work unsupervised in both teaching and assessment situations. As with any involvement in education, it is important that SPs are selected, trained and supported in their role, particularly when they are involved in high-stakes assessments or in evaluating qualified doctors' performance. SPs have also been used as covert patients to evaluate health services and the practice of individual doctors. Although planning and managing an SP service is time-consuming and can be costly in the initial stages, experienced SPs can replace clinicians in both teaching and assessments, which can lead to more standardized experiences for learners and cost savings over time. Recent international developments include consideration of SP accreditation, standards and certification as part of a drive to ensure high-quality education and training.

The skills: technical, non-technical and team working

Simulation takes place in a range of settings, but is probably most widely used and has had the most measurable impact in surgical settings, led by anaesthetists and surgeons. Taking an historical approach, Chapter 7 looks at surgical technical skills, highlighting some of the key drivers behind the introduction of simulation training and its impact on patient safety and error reduction. This chapter describes some of the key developments in developing and enhancing surgical skills. The need for further training and development via simulation training has been driven by the need to ensure higher standards of patient safety and error reduction; patient expectations of healthcare; the introduction of new operating procedures (such as laparoscopy); and technological advances (e.g. endoscopes, miniaturization of equipment and imaging technology). Technological advances have also enabled simulation to utilize different materials and harness computing power in the form of virtual reality simulators and other devices that facilitate and measure haptic (tactile) feedback in real time in order to ensure surgical technical skills are of a required standard. Such simulations enable doctors to improve operating techniques, particularly in the learning curve stage, when patients are deemed most at risk (Figure 1.2).

As the dividing line between surgeons, radiologists and other physicians becomes increasingly blurred with the more widespread use of minimally invasive procedures and interventional radiology, virtual reality simulators are being used to train a variety of health professionals. This brings its own challenges and opportunities. For example, as we are better able to measure fine response times and technique, simulation-based proficiency tests that incorporate ‘real-time’ pressures and s...