- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short History of the Modern Media

About this book

A Short History of the Modern Media presents a concise history of the major media of the last 150 years, including print, stage, film, radio, television, sound recording, and the Internet.

- Offers a compact, teaching-friendly presentation of the history of mass media

- Features a discussion of works in popular culture that are well-known and easily available

- Presents a history of modern media that is strongly interdisciplinary in nature

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Short History of the Modern Media by Jim Cullen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Print's Run

Publishing as Popular Culture

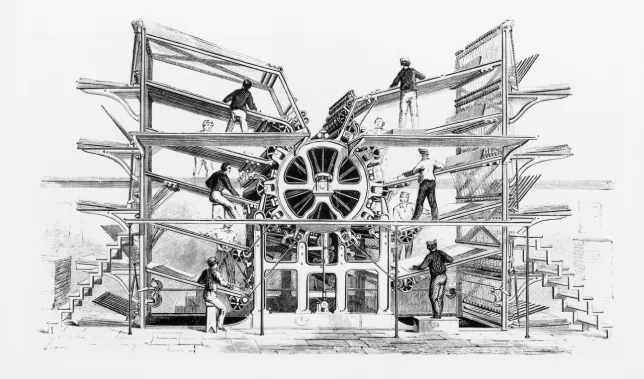

Figure 1.1 PRESSING MATTERS A cylindrical printing press from the mid-nineteenth century. A major advance from the hand-operated presses that only allowed one document to be produced at a time, cylindrical presses dramatically accelerated the pace and reach of the publishing business, establishing print as the dominant medium of popular culture in the United States.

(© Stapleton Collection/Corbis)

Overview

READING? For fun? Seriously?

It's not exactly that you hate reading (not all reading, anyway). For a student, reading is a fact of life. But, notwithstanding the occasional Harry Potter novel or ESPN story, most of the reading you do—other than facebook or text messaging, which doesn't really count here—is a means to an end: good grade, good degree, good job. Not typically something you do for kicks.

You may be interested to know that, in this regard, you're like the overwhelming majority of the human beings who have ever lived. Most—the ones who actually could read, as mass literacy is a modern invention—didn't read for fun, either. They, too, typically saw reading as a means to an end, and in a great many cases it was largely a matter of education in some form or another. (Originally, what we think of as books were actually scrolls; they were gradually replaced by the codex—handwritten pages bound on one side—which only began to disperse widely with the advent of the printing press in the fifteenth century.) But there was a specific historical moment, in the early nineteenth century, when reading suddenly did become something you would do for fun. There are a number of technological, economic, and cultural reasons for that, which I'll get to shortly. But the important thing to make clear at the outset is that the arrival of reading as an entertainment activity was a transformative moment in the history of the mass media—in an important sense, it marked the beginning of the history of the mass media—and one whose reverberations continue to this very day.

You can thank God for that. I mean this literally: I've mentioned technology, economics, and culture as important factors in the rise of reading, but in a Western-civilization context, and more specifically in an American context, religion was crucial. For much of recorded history—which is to say history that could be read, as opposed to committed to memory and spoken—the written word served a variety of purposes, among them law, finance, and art. But religion is at the top of the list.

In any event, reading for most of humankind was a practice of the elite. Indeed, in many cases you weren't allowed to read unless you were a member of the elite. The Roman Catholic Church, for example, didn't want just anybody reading the Bible, because someone might get what the clergy regarded as the wrong idea. For about 1500 years, the primary everyday interpreter of Christianity was the priest, who stood between—which is to say mediated between—Christ on the altar and his people in the pews. The priest read the word of God, as it was recorded in the Gospels and other sacred scripture, and explained what it meant.

The Catholic Church was always a hierarchically managed institution, and at the top of the chain was the Lord's presiding representative on earth, the pope, who was the final arbiter of scriptural authority. But when Martin Luther nailed those famous 95 theses on that church door in 1517, kick-starting the Reformation, the pope ceased to be reader-in-chief of the Western world. Now, suddenly, a series of Protestant churches competed for followers, organizing themselves in ways that ranged from networks of bishops to self-contained congregations. In such an environment, individual worshippers experiencing the word of God for themselves became a new possibility—and, in many cases, a new imperative. Such a quest was greatly aided by technological innovations in publishing, among them the ability to recombine letters on a metal plate, a technique known as moveable type, pioneered by the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg in the half-century before 1500.

In the intensity of their rebellion from the Catholic Church, these new Protestant sects varied widely. Some, like the Church of England (which became the Episcopalian Church in the United States), were content to largely follow traditional practices. Others, like the people we have come to know as Puritans, made more fundamental demands on their followers, among them the expectation that they would teach their children to read so that those children could forge their own relationship with God. Whether they were looking for economic opportunities, seeking to escape religious oppression, or simply trying to find a home they could call their own, many of these people—most from the British Isles, but some from other parts of Europe—made their way to English North America and founded colonies which, unlike French Canada or Spanish Latin America, were largely Protestant.

The religious emphasis on reading in North America made much of this territory, particularly New England, one of the most literate places on the face of the earth a century before the American Revolution. The first printing press was established at Harvard College in 1638. They didn't have indoor plumbing. But they did have prayer books.

So reading was primarily about God. But it wasn't solely about God. It was also about making money, planting crops, and baking bread. Annual publications called almanacs (which are still published every year) were among the first places where one could find information about such things. Almanacs were effective from a market point of view because, while the information they contained, like seasonal weather forecasts, was reasonably current, they could also be sold for a while before going out of date. So they made sense economically from a publishing standpoint as well as from a reading standpoint.

The all-time genius of the almanac business was a fellow named Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was born in Boston in 1706 and, as a child, worked for his older brother James, who was in the printing business, and in fact founded one of the first newspapers in America. James Franklin got in trouble around the time he began running a series of articles in his paper criticizing the Boston authorities, among them pieces that were submitted anonymously by someone who wrote as an old woman under the name of Silence Dogood (which was a play on the titles of books by the famous Puritan minister Cotton Mather). What nobody, not even James himself, realized was that Silence Dogood was not, in fact, an old woman. He was an adolescent boy named Benjamin Franklin. In the furor that followed, young Ben decided he'd better leave town—fast. He went to the rapidly growing city of Philadelphia, on its way to becoming the largest in North America.

Franklin would later take on a few other projects in his long life, among them working as a world-famous scientist, diplomat, and revolutionary with a hand in the creation of documents like the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. But his job, one that made him rich enough to do all those other things in his spare time, was in the printing business, and he had a particularly clever idea when it came to publishing almanacs. For his almanacs, Franklin created a fictional character—he dubbed him “Poor Richard”—who became a kind of mascot whose wit and wisdom would pepper the books and create a distinctive brand. (Pithy lines like “There are no gains without pains,” “Lost time is never found again,” and “Great spenders, poor lenders” are among Poor Richard's greatest hits.) Poor Richard's Almanac, issued annually between 1732 and 1758, was hugely successful, and a widely reprinted collection of Poor Richard's sayings, The Way to Wealth, is among the most famous works of popular culture of all time.

Poor Richard could be funny, but his humor always had a point, and that point usually had a moral tinge (ironically, Franklin, long associated with the maxim “early to bed, early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise,” was a notoriously late sleeper). When it came to the lingering power of religion in public life, the rules of the game tended to get bent more than broken. Insofar as there was secular writing to be found in North America in the decades preceding and following the American Revolution, it was still mostly for elite consumption. Newspapers, for example, were relatively expensive and had to be paid for in advance by subscription. They were typically aimed at high-end merchants with some kind of stake in the shipping business. Books were increasingly available, but they too were costly and typically also had to be paid for in advance by subscription (another one of Franklin's innovations was the first lending library in North America).

The American Revolution, in which Benjamin Franklin played such a large role, was a military, political, and diplomatic struggle, but it was also a communications battle. Great Britain, of course, had developed a print-media culture before its colonies did, but by the mid-eighteenth century those colonies were catching up rapidly. A rich discourse of political pamphlets, written by men with names like Adams and Jefferson, fed the argument on both sides in the years leading up to 1776 as well as the years following. The pivotal document, by all accounts, was Thomas Paine's legendary manifesto Common Sense, published in January of that year. Paine, who came to the colonies in 1774 from England with a letter of introduction from Franklin, proved crucially important in crystallizing a belief that the issue was no longer colonists having their rights as British subjects protected, but rather that it was time to move on and found a new nation. Paine's passionate polemic, and the intensity with which it was embraced, illustrates the way in which politics is a matter of winning minds as well as hearts.

But even after American independence was secured, the nation's culture remained literally and figuratively imported, and thus all the more pricey. The United States may have achieved its political independence in 1776, but in many respects, among them cultural, it remained a British colony for decades afterward. “In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?” asked the Reverend Sydney Smith, founder of the highbrow Edinborough Review, in 1820. It was a rhetorical question.

But even as Smith posed his sneering query, the United States was on the brink of a transformation. An important element in this transformation was technological; the early decades of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the young nation. Nowhere was this more evident than in the publishing industry. Up until this point, printing presses were just that: devices with which an individual pushed ink onto paper. With the advent of the cylindrical machines, in which paper rolled off presses powered by steam, it now became possible to run a much larger volume at a much lower cost. Publishers could now sell newspapers, books, and other forms of print at a fraction of their former price.

Which is why the nation's relatively high literacy rates proved so important. The fact that so many Americans could already read for religious reasons—and the fact that the United States was a large market with a shared language, growing cities, and a rapidly expanding transportation infrastructure—made it possible to turn the printed word into something it had never really been before: a true mass medium.

Mass publishing, in turn, created the prospect for a dramatic change in the way people read. Until the early nineteenth century, most reading was intensive, which is to say that readers tended to know a few books really well. The self-educated Abraham Lincoln, for example, was deeply knowledgeable about the Bible and Shakespeare, but read little else beyond that which he needed for his career as a lawyer. But from about the 1830s on, reading became increasingly extensive, which is to say that readers absorbed lots of different kinds of writing. Extensive reading was generally perceived to be less demanding, and more fun, which is why it was sometimes condemned. But it also became the dominant mode of reading in modern life. Most people today are extensive readers, not intensive ones. (We tend to be more intensive when it comes to things like listening to music, though technologies like digital downloads have broadened our palates.)

A new class of entrepreneurs was able to take advantage of the new extensive order and turn reading into a highly profitable form of entertainment. One such pioneer was Benjamin Day, publisher of the New York Sun, the first in a great wave of so-called penny papers to be founded in the United States. Founded in 1833, and rapidly followed by competitors like New York's Herald (1835), Tribune (1841), and Times (1851), as well as other daily newspapers around the country, the Sun specialized in running sensational stories that ranged from murder trials to an elaborate 1844 hoax of “Moon Men” landing in South Africa that actually prompted Yale University to send researchers to investigate. The penny papers were sold by the then-new methodology of the “London Plan,” which replaced paid subscription by having publishers sell batches of papers to so-called newsboys, who in turn sold them on the street to readers.

By the mid-nineteenth century, US cities were blanketed with newsprint that was passed from hand to hand. These papers varied in size; most were large “broadsheets,” and for a brief period in the 1840s so-called “mammoth” papers were poster-sized publications that could be read by more than one person at a time. Until the advent of photography later in the century, newspapers were illustrated with woodcuts. The primary source of revenue in the business was advertising, not sales. That's pretty much been true ever since.

The penny press was part of a larger reorganization of American politics. The middle of the nineteenth century was a democratic era in more than one sense. Ordinary people became part of the electoral process on a new scale as voters and citizens, and even those who were excluded, among them women and African Americans, could find a voice in the public sphere, particularly in journalistic venues like Freedom's Journal, a New York paper founded by free black men in 1827. Many newspapers embraced the avowedly egalitarian values of the Democratic Party generally and the presidency of Andrew Jackson in particular (though there were exceptions, like Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, which reflected the views of the opposition Whig Party). Democracy was not always pretty. Celebrations of freedom for some rested on a belief in the necessity of enslaving others; in many states, teaching slaves to read was banned. Mass opinion also often involved all manner of mockery of women, immigrants, or anyone who held unconventional views. This is one reason why respectable opinion often tried to avoid popular journalism, if not control it. Both proved impossible.

News and politics, in any case, were not the only kinds of writing that flourished in this golden age of print as popular culture. Gift books, forerunners of today's coffee-table books in their emphasis on arresting images and writing meant more for browsing than sustained reading, became common by the 1840s. So were women's magazines like Godey's Lady's Book, whose line illustrations of women in the latest couture—the term “fashion plate,” used to describe someone who looks great in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Medium Message

- Chapter 1: Print's Run: Publishing as Popular Culture

- Chapter 2: Dramatic Developments: The World of the Stage

- Chapter 3: Reel Life: The Art of Motion Pictures

- Chapter 4: Making Waves: Radio in American Life

- Chapter 5: Channels of Opportunity: The Arc of Television Broadcasting

- Chapter 6: Sound Investments: The Evolution of Sound Recording

- Chapter 7: Weaving the Web: The Emergence of the Internet

- Index