eBook - ePub

Oil Spill Risk Management

Modeling Gulf of Mexico Circulation and Oil Dispersal

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Oil Spill Risk Management

Modeling Gulf of Mexico Circulation and Oil Dispersal

About this book

This book is designed to help scientifically astute non-specialists understand basic geophysical and computational fluid dynamics concepts relating to oil spill simulations, and related modeling issues and challenges. A valuable asset to the engineer or manager working off-shore in the oil and gas industry, the authors, a team of renowned geologists and engineers, offer practical applications to mitigate any offshore spill risks, using research never before published.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oil Spill Risk Management by David E. Dietrich,Malcolm J. Bowman,Konstantin A. Korotenko,M. Hamish E. Bowman,Konstantin A. Korotenko,M. Hamish E. Bowman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Fossil Fuels. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Applied Oil Spill Modeling (with applications to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill)

Chapter 1

The 2010 Deep Water Horizon and 2002 Supertanker Prestige Accidents

1.1 Introduction

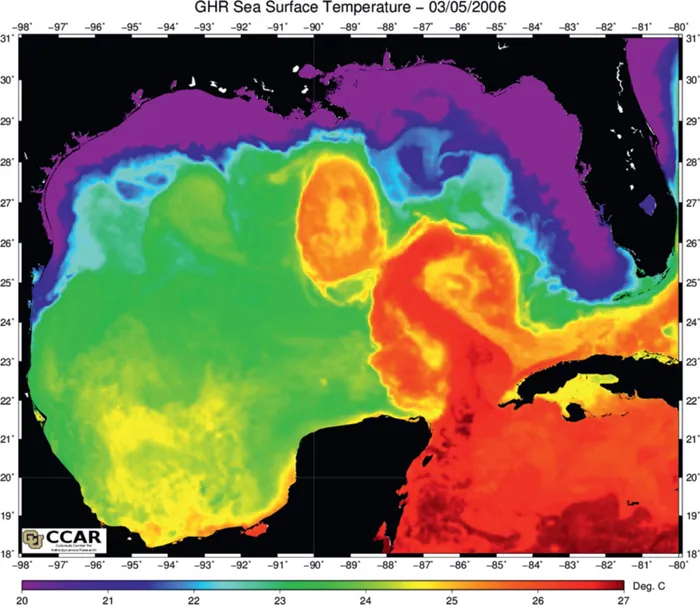

The Gulf of Mexico is a marginal sea forming the southern coast of the United States, bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. The Gulf has a surface area of ~ 1.6 million km2 with almost half of the basin being shallow continental shelf waters. However, in the Sigsbee Deep, an irregular trough more than 550 km long, the maximum depth is almost 4,400 m deep.1 The dominant circulation feature is the Loop Current, which flows into the Gulf from the Caribbean Sea through the Yucatan Channel between Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula and Cuba. The Loop Current subsequently feeds the Gulf Stream as it flows through the Florida Strait that lies between Florida, Cuba and the Bahamas.

The Gulf is a tropical and sub-tropical ocean basin boasting beautiful beaches, coral reefs, productive recreational and commercial fisheries, recreational boating, a unique Cajun heritage and extensive coastal wetlands supporting healthy ecosystems. The Gulf is considered by southern states to be an international treasure as well as a major economic resource for the southeastern United States.

Figure 1.1 Sea surface temperature satellite image of the Gulf of Mexico showing the Loop current, a major Loop Current eddy breaking off and associated small frontal eddies around the perimeter of the Loop Current eddy2.

There are about 3,850 oil rigs active in the Gulf, supporting over 50,000 drilling wells3. The major environmental threats to the Gulf are agricultural runoff and oil drilling accidents. There are also more than 600 natural oil petroleum seeps that are estimated to leak between 80 to 200,000 tonnes yr−14 5. The Gulf contains a large, elongated hypoxic zone south of the Mississippi River delta that runs east-west along the Texas-Louisiana coastline6. There are frequent “red tide” algae blooms that kill fish and marine mammals and cause respiratory problems in humans and some domestic animals when the blooms reach close to shore. In recent years, these have been plaguing the southwest and southern Florida coast, from the Florida Keys to north of Pasco County, Florida.

1.2 The Oil Spills Described

Between the 10th of April and the 15th July, 2010, it is estimated that the Deepwater Horizon/Macondo well released about 780,000 cubic meters of blowout material into the Gulf. The volume of Macondo crude oil that was suspended at depth greater than the Florida Straits7 sill depth may be the most important factor in the end, because the residence time8 of deep Gulf waters is estimated to be about 250 years [1, 2]. Deep Water Horizon oil material residues that are denser than the surface water but less dense than underlying bottom water migrate vertically, due to buoyancy forces, until they reach water having their same material density. This may be called the residue’s equilibrium depth, because water density increases with increasing depth and has much smaller horizontal variability (which also would have little effect because gravitational acceleration totally dominates total acceleration). Details of such vertical migration are not important except during the short migration time; the pressure forces acting on the water are the same as the forces acting on the residue material; thus, after such equilibrium depth is reached, the material simply goes with the flow (of the ambient water) to within exceptionally good approximation. Thus, the suspended oil material deep residues, like their ambient water, has a residence time of up to 250 years unless it is ingested into the deep ecosystem or geochemically modified. The ambient waters experience typically only a few meters vertical displacement, except during short lived, localized violent churning under hurricane eye walls.

Further warning is implied by an event involving the supertanker Prestige running aground off the coast Spain. The ship subsequently sank off the northwest coast of Spain9. It leaked only one tenth of the oil spilled from the BP/Macondo well; yet tar-balls from the Prestige spill were still deposited on far-away beaches. This led to a serious decline in tourism along the Bay of Biscay coast (in both Spain and France). It also gravely damaged local fisheries.

However, unlike the Gulf of Mexico, the Bay of Biscay has no deep basin that can trap suspended materials. Rather, the Bay is open to the Atlantic Ocean. Thus, spilled Prestige oil could eventually be dispersed throughout a significant portion of the world’s oceans.

The Deep Water Horizon oil spill10 in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 and the sinking of the Prestige supertanker event off the coast of Galatia, northwestern Spain in 200211 both released large amounts of crude oil into the ocean at great depths. Spilled oil fractions surfaced and polluted coastal regions including Gulf wetlands, open shorelands and Bay of Biscay beaches. Both seriously affected fishing and tourism industries. First responders were not adequately prepared to deal with such deep- water disasters as hundreds of workers painstakingly removed beached oil deposits and tar-balls.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon and the 2002 Prestige supertanker accidents differed in important ways. For example, in the Deep Horizon accident, about 10 times more hydrocarbon source material was leaked into the ambient ocean as compared to the Prestige event. Chemical dispersants were added to the plume in the Deepwater accident; none was added in the Prestige case.

The deep Gulf water and material residence times are estimated to be ~250 years [2, 3]. Unlike the Prestige oil spill, the Deep horizon waters and materials may be confined to the deep Gulf region (up to 3,500 deep) but probably of areal extent ~100 times less than the North Atlantic Ocean basin. Thus, much fewer opportunities are expected to exist for dispersal and dilution in the Gulf deep basins as compared with the North Atlantic Ocean. Eventually, the deep material will slowly decay by biogeochemical processes, or, as mentioned above, be mixed up to the surface by extreme weather events such as hurricanes.

1.3 How Much Material Remains in the Gulf?

Much of the subsurface well material that was not blown ashore or evaporated into the air may still be trapped in sub surface waters within the Gulf. Material suspended at depths greater than the ~700 m Florida Strait sill could possibly remain in the Gulf for centuries [1, 2], unless its density is altered by biogeophysical processes. On the other hand, future hurricanes may churn up deeply suspended materials (often in the form of tar-balls) to the surface and blow these ashore or out of the Gulf through the Florida Strait, as did 2012 Hurricane Isaac12.

Even a weak category 1 hurricane can churn material deeper than a few hundred meters to the surface, as did typhoon Kai-Tak13 [3]. Thus, it is not surprising that category 1 Hurricane Isaac churned up tar-balls and blew them ashore. Stronger hurricanes could churn deeper water to the surface, so the effects of Hurricane Isaac suggest that future hurricanes may lead to more damage from tar-balls, impacting Gulf beaches and wetlands. This would be especially apparent at locations where hurricane eye-wall winds blow toward the coast.

In summary, a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico may churn up deep cold water and mix it with warmer upper level Gulf waters, thus allowing these waters, with its suspended material, to escape through the Florida Straits and into the western Atlantic Ocean. However, some suspended oil materials do not mix readily with water (see Chapter 5), and thus may re-sink and settle to a new equilibrium depth closer to its depth before the hurricane.

1.4 The Role of Ocean Models to Explain what Happened

Economically important and environmentally sensitive questions can partly be addressed by well-tested and validated circulation and oil spill simulation models. Our contribution is to apply the DieCAST ocean model14 coupled with the Korotenko oil dispersion model (Korotenko et al., 2013) to shed light on probable transport, transformation and fates of oil residues released during the Deepwater Horizon (hereafter DWH) oil platform accident. We name the coupled model GOSM (Gulf Oil Spill Model). We use the DieCAST model to simulate Gulf circulation dynamics and vertical mixing processes and apply this information to investigate what possibly happened to the well blowout material. We also discuss the role of hurricanes over the long-term in churning up deep deposits and flinging them onto coastlines.

Winds, waves, currents, water density and temperature fields all determine the paths of elements of material leaked from the well site. These in turn affect the biogeochemical processes in the evolving element material properties. The Korotenko oil transport model features a Lagrangian particle-tracking method that is a cost-effective approach for the simulation of various events including oil spills [4].

References

1. D. Rivas, A. Badan, J. Ochoa, 2005: The Ventilation of the Deep Gulf of Mexico. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 35(10), 1762–1781. 2005

2. Fratantoni, D.M., R.J. Zantopp, W.E. Johns and J.L. Miller, 1997. Updated bathymetry of the Anegada-Jungfern Passage complex and implications for Atlantic inflow to the abyssal Caribbean Sea. J. Marine Res., 55, 847–860.

3. Tseng, Y.-H., S. Jan, D. Dietrich, I-I Lin, Y.-T. Chang and T.Y. Tang, 2010. Modeled oceanic response and sea surface cooling to typhoon Kai-Tak. Terr. Atmos. Sci., 21, 85–98.

4. Korotenk...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Part I: Applied Oil Spill Modeling (with applications to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill)

- Part 2: Special Topics in Oil Spill Modeling

- Appendix I: Notes on Modeling Hurricanes with DieCAST

- Appendix II: A Model Study of Ventilation of the Mississippi Bight by Baroclinic Eddies: Local Instability and Remote Loop Current Effects

- Index