- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book presents a comprehensive overview of the first longitudinal study of the downstream response of a major river to the establishment of a large hydropower facility and dams. Peace River, a northward flowing boreal river in northwestern Canada was dammed in 1967 and the book describes the morphological response of the 1200 km downstream channel and the response of riparian vegetation to the change in flow regime over the first forty years of regulated flows.

Beginning with a description of the effect of regulation on the flow and sediment regimes of the river, the book proceeds to study changes in downstream channel geometry on the main stem, on the lowermost course of tributaries, and on the hydraulic geometry, the overall morphology of the channel, and riparian vegetation succession. The river is subject to annual freeze-up and break-up, so a chapter is devoted to the ice regime of the river. A chapter compares the effects of two extraordinary post-regulation flood events. The penultimate chapter presents a prediction of the ultimate equilibrium form of the regulated river based on rational regime theory. An online database of all the main observations will provide invaluable material for advanced students of river hydraulics and geomorphology.

This book carefully brings together a range of studies that have been previously inaccessible providing a rare and comprehensive analysis of the effects of a big dam on a river, a river that itself represents an example of the kind of system that is likely to receive considerable attention in the future from dam engineers and environmentalists.

• An invaluable reference to river scientists, hydroelectric power developers, engineers and environmentalists

• Focus on a northward flowing boreal river, a type that holds most of the remaining hydroelectric power potential in the Northern Hemisphere

• Exceptional separation of water and sediment sources, permitting study of the isolated effect of manipulating one of the two major governing conditions of river processes and form

• Unique example of water regulation and both natural and engineered flood flows

• Detailed study of both morphological changes of the channel and of the riparian vegetation

• Online data supplement including major data tables and numerous maps. Details of the main observations and provides material for problem study by advanced students of river hydraulics and geomorphology are provided

Beginning with a description of the effect of regulation on the flow and sediment regimes of the river, the book proceeds to study changes in downstream channel geometry on the main stem, on the lowermost course of tributaries, and on the hydraulic geometry, the overall morphology of the channel, and riparian vegetation succession. The river is subject to annual freeze-up and break-up, so a chapter is devoted to the ice regime of the river. A chapter compares the effects of two extraordinary post-regulation flood events. The penultimate chapter presents a prediction of the ultimate equilibrium form of the regulated river based on rational regime theory. An online database of all the main observations will provide invaluable material for advanced students of river hydraulics and geomorphology.

This book carefully brings together a range of studies that have been previously inaccessible providing a rare and comprehensive analysis of the effects of a big dam on a river, a river that itself represents an example of the kind of system that is likely to receive considerable attention in the future from dam engineers and environmentalists.

• An invaluable reference to river scientists, hydroelectric power developers, engineers and environmentalists

• Focus on a northward flowing boreal river, a type that holds most of the remaining hydroelectric power potential in the Northern Hemisphere

• Exceptional separation of water and sediment sources, permitting study of the isolated effect of manipulating one of the two major governing conditions of river processes and form

• Unique example of water regulation and both natural and engineered flood flows

• Detailed study of both morphological changes of the channel and of the riparian vegetation

• Online data supplement including major data tables and numerous maps. Details of the main observations and provides material for problem study by advanced students of river hydraulics and geomorphology are provided

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Regulation of Peace River by Michael Church in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Hydrology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

On regulated rivers

1.1 Setting a context

Humans have dammed rivers since antiquity to control water levels and flows. Purposes have included direct control of water levels for water supply, flood protection, and navigation; water storage for domestic and irrigation use; diversion of waters for water and land management; and the capture of hydraulic power. The first significant dams were constructed in the arid Middle East, including both Mesopotamia and Egypt. The earliest known structure (in modern Jordan) dates from about 5000 years ago. In addition, early dams were constructed by the Hittites in Anatolia, and in the Harappan civilization of the eastern Indus plain. The purpose of these earliest water projects was water supply for domestic use and irrigation, and water level control.

The Romans advanced the art of dam construction dramatically by their invention of waterproof mortar. They established almost all of the basic dam designs and built structures—many still extant—up to 50 m in height, again principally for water supply and control. At the same time, Chinese hydraulic engineers were constructing extensive irrigation systems, exemplified by the reservoir and canal system at Dujiangyan on Minjiang (Min River) in Western Sichuan which remains, after 2200 years, operational (though much re-engineered) today. Engineers of the Islamic era initiated the use of mill dams, establishing the direct use of hydropower to accomplish work. Raising water and grinding power were the major applications.

These early developments came together in Western Europe in the Middle Ages with the employment of dams both for water control and for the development of water power. Many of the first adaptations occurred in the Low Countries, where water level control was critical for the effective use and secure occupation of land.

A water turbine was first demonstrated in France in 1832 and the first useful hydroelectric power was generated in 1878 at Cragside in Northumberland, United Kingdom (a small, domestic installation). Commercial hydroelectric power generation began in the United States in 1881 with the first Niagara Falls station and by 1890 there were more than 200 plants in the country. From the early twentieth century, hydro-generation became a widespread source of electric power and an integral part of comprehensive water management projects, exemplified by the Tennessee Valley project in the United States.

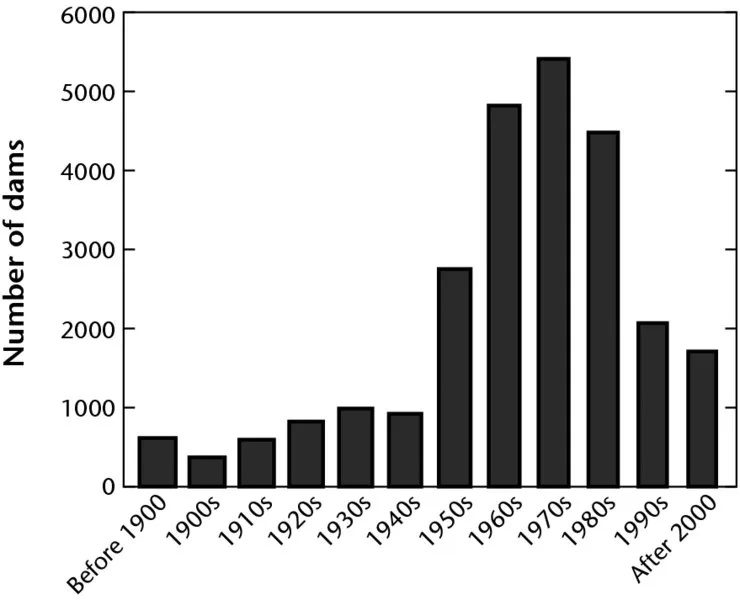

The 1911 commissioning of Roosevelt Dam on the Salt River, Arizona, marked the inception of the era of very large dams—ones capable of holding more than one cubic kilometer of water. Today there are more than 45 000 “high dams” (>15 m height) in the world (Figure 1.1) and more than a million dams overall. Hydroelectric power generation remains the reason for only a small percentage of those dams (∼3%), but essentially all of the largest ones that have the most dramatic impact on river morphology and ecological function.

Figure 1.1 Construction of large dams in the world. Summary to 2000 based on data of the International Commission on Large Dams as reported by World Commission on Dams (2005); figure for 2000 to 2010 is an estimate based on data in the World Commission report. Data exclude China that has about 22 000 large dams (nearly half the world total of about 46 000 dams), virtually all constructed since 1950.

The impact of large dams on the affected waterway is a comparatively recent concern. Early attention was drawn to the physical effects of Elephant Butte Dam (1915) on the channel of Rio Grande River (Lawson, 1925). Lane (1934) and Shulits (1934) drew more general attention to the topic. With the acceleration in construction of large dams after 1945, attention to the downstream morphological effects, in particular, was reemphasized. Along with the proliferation of large dam projects in the United States came a spate of papers reporting observations (Stanley, 1947; Hathaway, 1948; Mostafa, 1957; Hammad, 1972; summarized in Galay, 1983) and analyzing the physical problem of channel bed degradation (e.g., Tinney, 1962; Komura and Simons, 1967; Ashida and Michiue, 1971)—the most commonly observed phenomenon in the immediate downstream reach of the river.

Petts (1984a) subsequently gave a comprehensive overview of river regulation, extended by Petts and Gurnell (2005). He noted that regulation of an alluvial river alters the equilibrium between water flows and imposed sediment load that (presumably) previously existed, so that changes occur in one or more of cross-sectional geometry, gradient, and river planform in the attempt to regain equilibrium (see also Andrews, 1986; Carling, 1988). One should add riverbed sediment texture to the list. More specifically, Petts pointed out (1984a, p. 119) that the rate and direction of downstream channel change following regulation is governed by the relative frequency of sediment delivering events from unregulated tributaries and of reservoir release flows competent to move sediment resident in or delivered to the mainstem. He described channel adjustments in the regulated mainstem as follows:

- passive response: mainstem flows reduced below the level of competence to move the riverbed sediments, so the active channel simply shrinks within the preexisting channel zone by progradation of vegetation (in this case there may be no further morphological response; the channel has, in effect, ceased to be an alluvial channel);

- degradation due to sediment “starvation” downstream of the dam, by far the most commonly documented response (see Galay, 1983; also Wolman (1967); Williams and Wolman (1984)), largely in rivers with beds composed of sand or fine gravel that can still be mobilized by the regulated flows;

- aggradation due to sediment inputs to the river that it is no longer competent to move downstream, the most common source being tributary inputs of relatively coarse sediment (e.g., Petts, 1984b).

Responses are commonly complex, both spatially and temporally (Petts and Gurnell, 2005). For example, degradation immediately downstream of the dam may be succeeded by aggradation farther downstream as the evacuated sediment is flushed into distal reaches with lower gradient and transport competence. Progradation of vegetation into the former channel zone may promote fine sediment trapping during high flows, hence aggradation may follow channel shrinkage. With the lapse of time, initial aggradation at tributary junctions may steepen gradients sufficiently to promote onward movement of sediment, shifting the locus of aggradation downstream. Furthermore, as the period of regulation lengthens, the probability increases for competent flows to occur as the result of unusual releases from the dam or extraordinary tributary inflows. Complex response may also result from changes in bed material downstream, so that proximal gravel-bed reaches may behave differently than distal sand-bed channels (e.g., Pickup, 1980; Gaeuman et al., 2005). Farther downstream, as well, the fraction of the contributing area that is regulated declines, so the reassertion of a more natural hydrological regime attenuates many of the proximal effects (Gregory and Park, 1974).

Since Petts's early review, a detailed survey of the downstream effects of dams in the United States has been contributed by Williams and Wolman (1984), whose investigations strongly reinforced the impression that the most common proximal response is degradation, whilst Chien (1985) has presented a systematic discussion of degradation processes, giving particular attention to sedimentary aspects. Both of these studies were focused on sand-bed streams.

Brandt (2000), in a new review, focused attention on the gradation response to regulation of a river by more detailed consideration of the disturbed balance of sediment load and sediment transporting capacity. Straightforwardly put, if post-regulation load is less than transporting capacity, degradation will occur, provided that flows remain competent to move channel bed material, whereas, if sediment load exceeds transporting capacity or competence (a common situation immediately below tributary junctions), aggradation will occur. Brandt pointed out that the degradational response is apt to be vertical (i.e., channel incision will occur) if the streambed sediments are fine (silt, sand, and possibly pebble gravel), but lateral (banks and bars erode) if the sediments are coarse. Grams et al. (2007) have distinguished these processes as “incision” and “evacuation” (of sediment). Conversely, aggradational response is apt to be vertical if sediments are coarse (which may also entail some widening), but lateral, leading to the channel becoming narrower and deeper, if the sediments are fine. The differing responses are related to the different modes of transport and deposition of coarse and fine materials and associated characteristic differences in the relative strength of river bed and banks. Gaeuman et al. (2005) have described an interesting range of these responses in a river that undergoes a gravel-to-sand transition.

Surian and Rinaldi (2003) further characterized channel responses to flow regulation by focusing on morphological style, noting the tendency for regulated channels to assume more simple morphologies (to move from braided toward single thread form, for example) and, concomitantly, to incise and become narrower. Combining these insights, based on an exhaustive survey of regulated Italian rivers, with knowledge of characteristic associations between channel sediments and channel style, their results are broadly consistent with Brandt's conclusions.

Grant et al. (2003) have codified probable morphological responses to regulation by comparing measures of sediment supply and of competent flow duration before and after regulation, and Schmidt and Wilcock (2008) have advanced this topic to semiquantitative precision by proposing metrics for the prediction of the geomorphological effects of flow regulation and sediment interception at dams. Most recently, Grant (2012) has essayed the general p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Contributing authors

- Preface

- 1 On regulated rivers

- 2 The regulation of Peace River

- 3 Downstream channel gradation in the regulated Peace River

- 4 Tributary channel gradation due to regulation of Peace River

- 5 The hydraulic geometry of Peace River

- 6 Ice on Peace River: effects on bank morphology and riparian vegetation

- 7 Post-regulation morphological change on Peace River

- 8 Studies of riparian vegetation along Peace River, British Columbia

- 9 The response of riparian vegetation to flow regulation along Peace River, Alberta

- 10 The floods of 1990 and 1996 on Peace River

- 11 The future state of Peace River

- 12 Implications for river management

- Appendix: data files online

- Index

- End User License Agreement