Emergency Point-of-Care Ultrasound

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Emergency Point-of-Care Ultrasound

About this book

Featuring contributions from internationally recognized experts in point-of-care sonography, Emergency Point-of-Care Ultrasound, Second Edition combines a wealth of images with clear, succinct text to help beginners, as well as experienced sonographers, develop and refine their sonography skills.

The book contains chapters devoted to scanning the chest, abdomen, head and neck, and extremities, as well as paediatric evaluations, ultrasound-guided vascular access, and more. An entire section is devoted to the syndromic approach for an array of symptoms and patient populations, including chest and abdominal pain, respiratory distress, HIV and TB coinfected patients, and pregnant patients. Also included is expert guidance on administering ultrasound in a variety of challenging environments, such as communities and regions with underdeveloped healthcare systems, hostile environments, and cyberspace.

Each chapter begins with an introduction to the focused scan under discussion and a detailed description of methods for obtaining useful images. This is followed by examples of normal and abnormal scans, along with discussions of potential pitfalls of the technique, valuable insights from experienced users, and summaries of the most up-to-date evidence.

Emergency Point-of-Care Ultrasound, Second Edition is a valuable working resource for emergency medicine residents and trainees, practitioners who are just bringing ultrasound scanning into their practices, and clinicians with many years of sonographic experience.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1

Physics

1

How Does Ultrasound Work?

Introduction

What is Ultrasound?

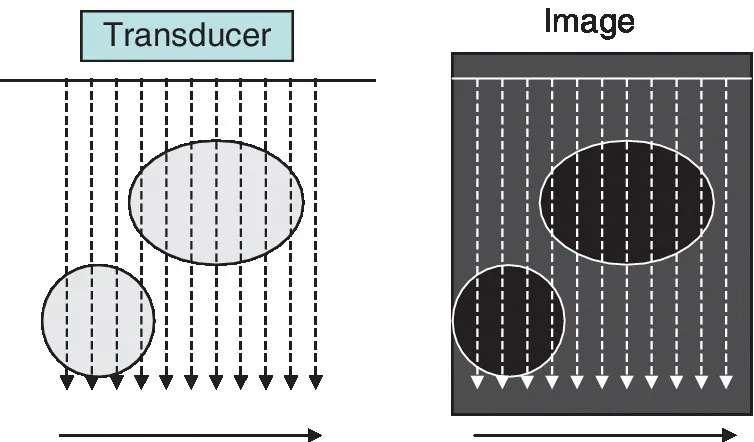

Constructing the Image

Making Sense of Ultrasound Images

- the spatial definition of tissue boundaries;

- relative tissue reflectivity;

- echo‐texture; and

- the effect of tissue on the transmission of sound.

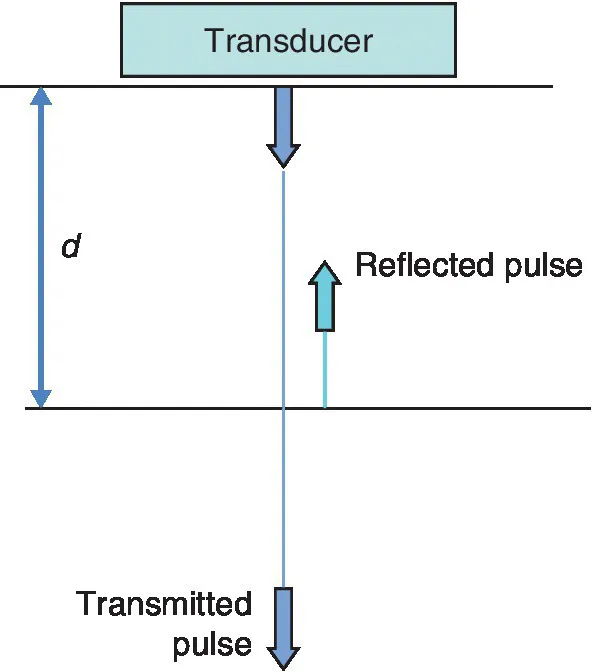

What Happens to a Pulse of Sound as it Travels Through a Patient?

Reflection

Specular Reflection

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- About the Companion Website

- Introduction

- Part 1: Physics

- Part 2: Ultrasound by Region

- Part 3: Paediatrics

- Part 4: Adjunct to Practical Procedures

- Part 5: Syndromic Approach

- Part 6: Different Environments

- Appendix A1: Selected Protocols for Cardiac and Critical Care Ultrasound

- Index

- End User License Agreement