eBook - ePub

Handbook of Psychology, Health Psychology

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Psychology, Health Psychology

About this book

Psychology is of interest to academics from many fields, as well as to the thousands of academic and clinical psychologists and general public who can't help but be interested in learning more about why humans think and behave as they do. This award-winning twelve-volume reference covers every aspect of the ever-fascinating discipline of psychology and represents the most current knowledge in the field. This ten-year revision now covers discoveries based in neuroscience, clinical psychology's new interest in evidence-based practice and mindfulness, and new findings in social, developmental, and forensic psychology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Psychology, Health Psychology by Irving B. Weiner,Arthur M. Nezu,Christine M. Nezu,Pamela A. Geller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Overview

Chapter 1

Health Psychology: Overview

What Is “Health”?

Policy, Ideology, and Discourse

A Taxonomy for Interventions

Conclusions

References

What is “Health”?

Before discussing health psychology, it is helpful to clarify what is meant by the term health. To understand the use of this term, we must take a dip into etymology, the study of the origin of words. Etymologists suggest that the word health originated in Old High German and Anglo-Saxon words meaning “whole,” “hale,” and “holy.” The etymology of heal has been traced to a Proto-Indo-European root kailo- (meaning “whole,” “uninjured,” or “of good omen”). In Old English, this became hælan (“to make whole, sound, and well”) and the Old English hal (“health”), the root of the adjectives “whole,” “hale,” and “holy” and the greetings “Hello,” “Hallo,” or “Hi.”

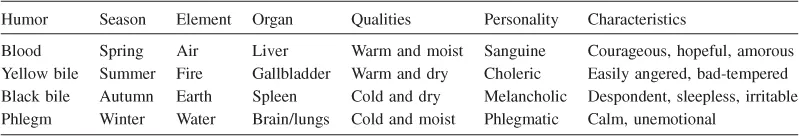

Galen (C.E. 129–200), the early Roman physician, followed Hippocratic tradition in believing that hygieia (health) or euexia (soundness) occurs when a balance exists between the four humors: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. Galen believed that the body's constitution could be put out of equilibrium by excessive heat, cold, dryness, or wetness. Such imbalances might be caused by fatigue, insomnia, distress, anxiety, or food residues from eating the wrong quantity or quality of food. For example, an excess of black bile would cause melancholia. The theory was closely related to the theory of the four elements: earth, fire, water, and air (Table 1.1). Some current health beliefs are direct descendants of ancient Greek and Roman theories of medicine. In winter, when it is chilly and wet, we might worry about catching a cold, caused by a buildup of phlegm. In summer, we might worry about not drinking enough water to avoid becoming hot and bothered, or bad-tempered. The idea of health as an optimum balance between elements of life is an principle that remains relevant to modern constructions of health. In Chinese medical theory, the yin-yang balance concept is fundamental, along with microcosm–macrocosm correspondences (tien-jen-hsiang-ying) and harmony (t ‘iao-ho) (Kleinman & Lin, 1981). The concept that health consists of a balance of elements is a core feature across diverse cultures and times. In valuing balance, Western and Eastern cultures have not changed in 2,000 or 3,000 years.

Table 1.1 Galen's Theory of Humors

Health, illness, medicine, and health-care stories are plentiful in the mass media, especially about the dread diseases: cancer, HIV, and, more recently, obesity. The Internet spews out stories by the million on every health-related topic at the touch of a few keys. A popular search engine revealed a total of 1.24 billion items on “health.” This total may be compared to the lower figure of 1.19 billion items on “sex” and a meager 0.568 billion items on “football.”

In spite of universal interest, there is not a single accepted definition of health. Experts and laypeople alike act as if they know what is meant by the term, and so there is no pressing need to define it. This lacuna of presumption is a source of confusion in the theory and policy of health care. The World Health Organization (Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, June 19–22, 1946) defined health as follows: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This definition has obvious flaws. One must doubt whether any living person could ever reach “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being.” More familiar to most people is the opposite state: incomplete physical, mental, and social well-being, with the presence of illness or infirmity. Apart from the idealism of the WHO definition, it missed key elements of health, elements that many believe to be fundamental. Health is a multidimensional state, which is complex, complicated, and nonreductive.

Any health psychologist would insist that health has psychological aspects that must be included in any definition of health. Psychological processes such as cognition, imagination, volition, and emotion are all mediators of health experience. The adjective psychosocial is preferred to the more restrictive psychological, denoting that human behavior within social interaction influences the wellness–illness continuum (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Culture (e.g., Landrine & Klonoff, 1992) and economic status (e.g., Adler et al., 1994; Kawachi et al., 1997) are also mediators of health. Spirituality can significantly strengthen resilience in the face of illness, grief, and suffering (e.g., Thoresen, 1999). For many people, spirituality is an essential part of what it means to be human. Sawatzky, Ratner, and Chiu (2005) carried out an extensive literature search of 3,040 published reports, from which 51 studies were included in a final analysis. They reported a bivariate correlation between spirituality and quality of life of 0.34 (95% CI: 0.28–0.40). The authors concluded: “The implications of this study are mostly theoretical in nature and raise questions about the commonly assumed multidimensional conceptualization of quality of life” (p. 153). In one's practice as a health psychologist, personal leanings as a believer or nonbeliever are not an issue; the patient is the focus, and the patient's spiritual or religious needs can never be discounted. They can be a potent force in rehabilitation, therapy, or counseling.

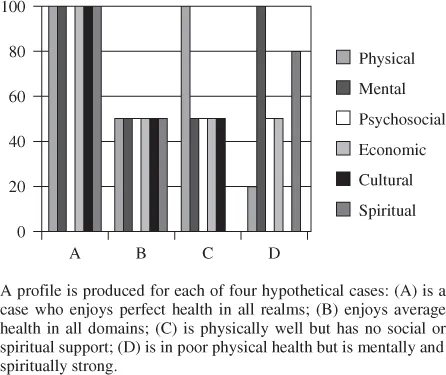

With these thoughts in mind, I offer the following definition of health: Health is a state of well-being with physical, mental, psychosocial, educational, economic, cultural, and spiritual aspects, not simply the absence of illness. The principle of compensation enables any one element that is relatively strong to compensate for lack in one or more other elements. If one or more of the elements is diminished, a person may yet experience a positive and sustainable state of health. This feature is illustrated in Figure 1.1 (see cases C and D). Thus balance and compensation are as important as the individual strength of any one particular element.

Figure 1.1 A multidimensional theory of health

Researchers have struggled with the possibility of measuring health by using a single universal scale of measurement. The complexity of the task is evidenced by the structure of scales developed to measure health. Four leading scales are:

1. The Nottingham Health Profile (Hunt, McKenna, McEwan, Williams, & Papp, 1981) scored 0–100 using six subscales for Physical Mobility, Sleep, Emotional Reactions, Energy, Social Isolation, and Pain.

2. The SF-36 (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) score 100–0, using eight subscales for Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Role Emotional, Vitality, Mental Health, Social Functioning, Bodily Pain, and General Health Perceptions.

3. The COOP/WONCA (Nelson et al., 1987) scored 1–5, using six subscales for Physical Fitness, Feelings, Daily Activities, Social Activities, Change in Health, and Overall Health.

4. The EuroQol (Williams, 1990) scored 1–3, using five subscales for Mobility, Self-Care, Usual Activities, Pain/Discomfort, and Anxiety/Depression.

Essink-Bot, Krabbe, Bonsel, and Aaronson (1997) factor-analyzed the four scales and derived factors that correspond to two of the seven dimensions in the present theory, physical health and mental health. Empirical support for the five remaining dimensions is available in multiple reviews and meta-analyses: psychosocial (e.g., Uchino, Uno, & Holt-Lunstad, 1999), economic status (e.g., Douglas, 1950; Marmot et al., 1991), educational (e.g., Gesteira, 1950), culture (e.g., Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, 1978; Office of Behavior and Social Science Research, 2004; Pelletier-Baillargeon & Pelletier-Baillargeon, 1968), and spirituality (e.g., Ellison & Fan, 2008; Thoresen, 1999). None of these mediators of health is a new discovery. We have been slow as a discipline to acknowledge their primary role in our construction of what it means to be healthy.

The principle of compensation has a parallel in economics in the form of resource substitution: When wants and needs exceed the available resources, then a different resource will be used to fulfill those wants and needs. A similar principle operates between health and education, in which the absence of one resource is less harmful if other resources can substitute for it (Ross & Mirowsky, 2006). The balance of the seven ingredients in this recipe for health should be considered when attempting an account of a particular person's state of health.

The trends shown later in Figure 1.3 indicate that research on cultural differences in health behavior is gradually increasing. Continuation of this trend will enable theory and practice to converge more effectively in creating interventions relevant to those who most need them. In illustrating this point, Adams and Salter (2007) focused on African settings. The authors explored three culture-specific examples of health concerns from Africa: the prominent experience of personal enemies, epidemic outbreaks of genital-shrinking panic, and fears about sabotage of vaccines in immunization campaigns. One can envision totally different health psychologies emerging from diverse cultures. The health psychology of high-income countries, as currently formulated, could well prove almost irrelevant to cultures existing outside of these zones. Within a country, widespread cultural, socioeconomic, and ethnic differences are evident in many aspects of health experience. Banthia, Moskowitz, Acree, and Folkman (2007) measured religiosity, prayer, physical symptoms, and quality of life in 155 U.S. caregivers. The findings indicated that prayer was significantly associated with fewer health symptoms and better quality of life only among less educated caregivers. This finding shows how a resource from one domain (spirituality) can compensate for a lack in another (education).

Policy, Ideology, and Discourse

Health psychology is concerned with the application of psychological knowledge and techniques to health, illness, and health care. The objective is to promote and maintain the well-being of individuals, communities, and populations. The field has grown rapidly, and health psychologists are in increasing demand in health care and medical settings. Although the primary focus has been clinical settings, interest is increasingly directed toward interventions for disease prevention, especially sexual health, obesity, alcoholism, and inactivity, which have joined smoking and stress as targets for health interventions.

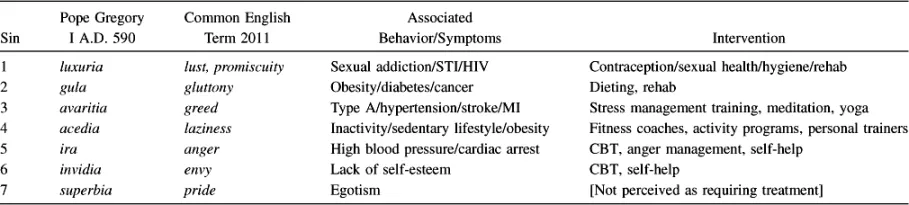

It is evident that everyday concepts of healthy living have advanced little since classical times. Current public health priorities and the associated interventions correlate with ancient concepts of the evils in society that need to be amended. Pope Gregory I was familiar with them all when, in A.D. 590, he defined the seven deadly sins (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Seven Deadly Sins, Common English Terms, Behavioral Counterparts, and Available Interventions

A holistic tendency, embracing a biopsychosocial approach, is increasingly evident within health care. Health psychologists are working in collaboration with multidisciplinary teams at different levels of the health-care system to perform a variety of tasks: carrying out research; systematically reviewing research; helping to design, implement, and evaluate health interventions; training and teaching; consultancy; providing and improving health services; carrying out health promotion; designing policy to improve services; and advocating social justice so that people and communities are enabled to act on their own terms.

A community perspective, promoting strategies for social change at the local level that can facilitate improved health and well-being, complements a focus on individuals. Within the latter paradigm, a communitarian perspective to health work can generate alternative methods of interventions. In working toward social justice and the reduction of inequities, people's rights to health and freedom from illness are viewed as a responsibility of planners, policy makers, and leaders of people wherever they may be (Marks, 2004). Individual and community approaches offer much potential for reducing health inequalities, but they both can also potentially distract attention from the broader structural causes of ill health. Health psychology training in masters and doctoral programs is available both within the community psychology framework and in mainstream health psychology (Marks, Sykes, & McKinley, 2003). I discuss the community approach later in this chapter. First, I deal with the dominant paradigm focused on the health of the individual.

The dominan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Editorial Board

- Handbook of Psychology Preface

- Volume Preface

- Contributors

- Part I: Overview

- Part II: Causal and Mediating Psychosocial Factors

- Part III: Diseases and Disorders

- Part IV: Health Psychology Across the Life Span

- Author Index

- Subject Index