![]()

1

Introduction

Investing in private equity, hedge funds and real assets – such as infrastructure, real estate, forestry and farmland, energy and commodities – has gained considerable momentum in recent years. These assets are often called “alternatives” as their investment history is still relatively short and, unlike traditional asset classes, they are rarely traded in public markets.1 Investors have been attracted by the superior returns that alternative assets may offer. Moreover, as returns are found to be correlated less with traditional asset classes, alternative assets have been regarded as attractive investments helping asset allocators diversify their portfolios. At the same time, it has been argued that the potential returns of traditional asset classes have diminished. Specifically, public stock markets have become increasingly efficient, limiting investors' potential to achieve excess returns by investing in undervalued stocks. In the bond market, yields have declined substantially since the 1980s thanks to successful central bank policies aimed at reducing inflation expectations and restoring confidence in monetary policy.

1.1 ALTERNATIVE INVESTING AND THE NEED TO UPGRADE RISK MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

At the end of 2011, private equity funds, hedge funds and funds investing in real assets were estimated to be managing around USD 4 trillion. This amount may still seem small compared with the size of the global equity and debt securities markets, whose volume totalled almost USD 150 trillion in 2010. However, the market for alternatives has grown much faster than traditional investments. Just three decades ago alternative assets totalled only a few billion US dollars, implying a compound annual growth rate of more than 25%. For some investors, especially endowments, foundations and family offices, alternative investing is no longer considered a niche strategy, but instead is part of their core portfolio. In fact, some asset allocators have invested as much as half their capital in alternatives, a few individual institutions even more. Pension plans, the largest investors in private equity, real assets and hedge funds, generally have a comparatively less pronounced exposure in terms of the total amount of assets under management (AuM). However, some of the largest pension funds worldwide, such as the California Public Employees' Retirement System (CalPERS), the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board or the Washington State Investment Board, have invested 20% and more of their assets in alternatives.

The United States has remained the largest market for alternative investing, absorbing more than 50% of the capital deployed in private equity, real assets and hedge funds. At the same time, US investors have been the world's largest capital source for alternative investments. However, Europe and, more recently, advanced Asia and emerging economies have been playing catch-up, both as a destination and source of capital. As regards the latter, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) have played a particularly important role, helping recycle their countries' current account surpluses and raising foreign exchange reserves by investing in asset classes whose liquidity characteristics make them inaccessible for central banks. Thus, alternative investing has become a global business, with cross-border transactions helping regional markets become increasingly integrated.

However, it appears that the development of investors' risk management capabilities has not always kept pace with their growing exposure to alternative assets. During the global financial crisis in 2008–2009, a significant number of investors, and especially those with a substantial exposure to alternative assets, were faced with an acute lack of liquidity. The sudden shortage of liquidity took investors by surprise. The majority of them had based their liquidity planning on cash flow models whose parameters were essentially static. However, as financial markets shut in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the autumn of 2008, the model parameters shifted rapidly due to sharply reduced distributions from private equity funds and similar partnerships investing in real assets, the suspension of redemptions by hedge funds, and increased margin calls and collateral. Many institutional investors thus found that their short-term liabilities either proved to be much more inflexible than they had thought or rose unexpectedly in the face of the crisis.

The financial turmoil that spread rapidly around the globe made a key characteristic of long-term investing in private equity funds and similar structures suddenly highly transparent. Organized as limited partnerships, such funds are designed to shield fledgling portfolio companies in their early stages and those in need of being restructured from disruptive market influences, and to assure these companies' continued financing. This requires patient capital, with long-term investors in limited partnerships essentially locking away their capital for 10 years or even longer. While investors, or limited partners in private equity funds, were aware of the fact that they had to make long-term capital commitments in order to be able to harvest an illiquidity risk premium, during the crisis it turned out that many of them had underestimated liquidity risk in two important ways. First, capital calls, or so-called contributions, of committed capital to private equity funds and similar structures are unknown in terms of their timing and size. Although capital calls slowed substantially during the Great Recession, distributions fell even faster as exit markets essentially closed. Thus, limited partners were exposed to funding risk, which represents a key challenge in terms of liquidity management. Second, investors who had relied on the secondary market as a means to liquidate (parts of) their portfolios found out that transaction volumes fell sharply precisely when liquidity was needed most.

University endowments in the USA were hit particularly hard, and given their payout requirements several of them were forced into distressed sales of assets. However, the problems were by no means confined to university endowments. In fact, as we discuss throughout this book, even some of the largest pension funds were confronted with significant liquidity problems as funding risk and market liquidity risk in the secondary market surged to unprecedented highs. As investors attempted to avoid defaulting on their commitments amid an increasingly illiquid secondary market, they decided to sell liquid parts of their portfolios, such as public stocks, to generate liquidity (Ang et al., 2011). In some cases, the pressure to divest was amplified by a substantially larger-than-expected decline in the mark-to-market value of investors' portfolios, triggering “sell” signals by their asset allocation models. In the event, many investors incurred significant losses (Ang and Kjaer, 2011; whose analysis is summarized in Chapter 6).

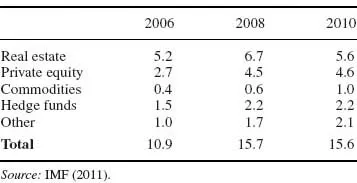

To be sure, the crisis did not generally undermine investors' belief in the benefits of alternative investing. While some investors did reduce their allocation to alternatives in an effort to align assets more closely with liabilities and to comply with accounting and regulatory pressures, others maintained their allocations or even raised them, for example, to address underfunded liabilities (WEF, 2011). As far as pension funds are concerned, a recent survey by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2011) found that their overall exposure to alternative assets was virtually unchanged between 2008 and 2010 (see Table 1.1), as new investments essentially kept pace with distributions by limited partnership funds or offset other divestments. Importantly, the share of alternative assets in pension funds' total AuM thus remained significantly higher than prior to the crisis, when many investors increased their allocations to alternatives substantially. As a result, pension funds' average exposure to alternative assets in 2010 exceeded their relative allocation in 2006 by more than 40%, with private equity contributing particularly strongly to this increase.

Table 1.1 Allocation of pension funds to alternative asset classes, as a percentage of total assets under management

Arguably, the most recent turmoil in Europe's sovereign debt market might have contributed to institutional investors' continuous commitment to alternatives. As the IMF (2012) points out, the debt crisis has reinforced the notion that no asset can be viewed as truly safe. Instead, recent rating downgrades of sovereigns previously considered to be virtually riskless have reaffirmed that even highly rated assets are subject to significant risks. The IMF (2012) estimates that the decline in the number of sovereigns whose debt is considered safe could remove some USD 9 trillion from the supply of safe assets by 2016, or roughly 16% of the projected total. This decline is accentuated by a reduction in the private supply of safe assets as poor securitization in the USA has tainted these securities and more stringent regulation has impaired the ease with which private sector issuers may produce assets that are deemed “safe”.

At the same time, heightened uncertainty, regulatory reforms and crisis-related responses by central banks have driven up demand for safe assets. Given the shrinking set of assets perceived to be safe, growing global supply/demand imbalances are feared to increase the price of safety and compel investors to move down the safety scale as they scramble to obtain scarce assets. The IMF (2012) warns that safe asset scarcity could lead to global financial instability resulting from short-term volatility jumps, herding behaviour and runs on sovereign debt. In this environment, where global supply/demand imbalances may seriously distort the benchmark pricing of sovereign debt, investors may be compelled further to invest in alternatives to generate higher returns. Note, in this context, that in the first nine months of 2012 10-year US Treasury bonds averaged around 1.8%, implying significantly negative yields in real terms. Yields on 2-year US Treasuries averaged 0.28% during this period, while strong demand for German and Swiss 2-year bonds drove even nominal yields into negative territory. A third round of quantitative easing in the United States, unconventional monetary policy measures in the euro area, the United Kingdom and Japan, and further monetary easing in several emerging markets indicate that policy makers are committed to keeping interest rates low in the foreseeable future.

While investors have remained committed to alternatives, their experience in the recent global financial crisis has led many of them to reconsider their investment strategies with regard to private equity, hedge funds and real assets. Generally, this review has focused on two aspects of the allocation process. First, from a top-down perspective investors have revisited their asset allocation models in light of their liability profiles and risk appetite (WEF, 2011). Second, from an asset-specific point of view a growing number of investors have thought about alternative ways to achieve their target exposure to specific asset classes. As a growing number of investors have begun to adjust their asset allocation strategies, they have fostered visible changes in the alternative investment industry.

As far as portfolio construction is concerned, in the pre-crisis era most investors relied on models that were designed to construct efficient portfolios on the basis of historical asset returns, their variance and their correlation with returns in other asset classes. However, in the Great Recession such mean/variance approaches proved to be too static, as systemic risk rapidly pushed correlations upwards. As a result, gains from diversification often proved to be illusive, and investor portfolios turned out to be far less robust than the models had suggested.

Against this background, several investors have begun to implement less granular asset allocation frameworks that focus more on asset-specific risks as differentiating factors generating diversification benefits – as opposed to (less-than-perfect) return correlations that play a key role in the standard mean/variance approach. This applies to both traditional and alternative asset classes. As far as the latter are concerned, the risk factor allocation approach recognizes that private equity, hedge funds and real assets are subject to fundamentally different risks. Private equity, for instance, is subject to liquidity risk, in addition to equity risk. By comparison, investing in hedge funds is generally less illiquid than commitments to private equity funds. At the same time, however, hedge funds tend to be highly leveraged and hence subject to credit risk. As far as real estate is concerned, investors expect to be compensated for the term risk they take – a risk component which is absent in private equity investments. It is this heterogeneity of investment risk and the associated risk premiums that offers diversification gains and hence helps improve risk-adjusted portfolio returns.

1.2 SCOPE OF THE BOOK

Harvesting different risk premiums requires specific risk management approaches. In this book, we focus primarily on the illiquidity risk premium that structurally illiquid asset classes may offer. Two clarifications are in order. First of all, a broad range of asset markets may become illiquid in periods of severe financial stress. In the recent global financial crisis, the markets for corporate debt, collateralized debt obligations and securitization virtually shut down. There is a rapidly expanding literature on cyclical illiquidity, discussing its causes and effects and especially the role of banks (e.g., Shin, 2010; Tirole, 2011 and the literature discussed therein). In contrast to asset classes that may become illiquid thanks to financial turmoil and heightened risk aversion, investors in structurally illiquid asset classes, such as private equity and real assets, are aware ex ante of the risk they take. In fact, as we argue in this book, it is precisely this risk, and more specifically the associated risk premium, that attracts investors to these asset classes. Not all investors are able to harvest this risk premium, however. As a matter of principle, only long-term investors can, whose liability profile allows them to lock capital in for a prolonged period of time, usually 10 years or more. Harvesting the illiquidity risk premium requires specific risk management techniques, however, which are the subject of this book.

Second, we shall not consider hedge funds. While they are generally considered to be part of the alternative investment universe, they show a different risk profile compared with private equity and real assets. Although redemptions may be suspended in certain circumstances, the organization of hedge funds is fundamentally different from private equity funds and limited partnerships investing in real assets, making the former less illiquid. At the same time, hedge funds are subject to risks that are idiosyncratic to this asset class, requiring different risk management tools whose discussion is beyond the scope of this book.

This leaves us with long-term investing in private equity and real assets as two highly illiquid alternative asset classes. But this is still too broad a focus for what this book attempts to achieve. Instead, it is important to recognize that there are different ways to invest in private equity and real assets. As investors have revisited their exposure to alternative assets, and more specifically to private equity and real assets, some of them have decided to pursue alternative routes to fund investing. To begin with, some large investors have engaged in direct investments, essentially competing with partnerships in acquiring assets. Others have put increased emphasis on co-investments alongside funds they have committed capital to. While there is little systematic evidence on the significance of co-investments and direct investments in investors' portfolios, anecdotal evidence suggests that at least in individual cases (notably some Canadian pension funds) these forms play an important role. Yet others (i.e., some sovereign wealth funds) have acquired stakes in the management company of private equity firms. Finally, a rising number of investors have sought to set up managed accounts with asset managers instead of committing capital to limited partnerships.

As investors have looked into alternative ways of investing in private equity and real assets, many fund managers have adjusted their own business models. Several large private equity firms – such as the Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group or Kohlberg Kravis Roberts – have transformed themselves into alternative asset managers, offering their clients a broad range of products, including through managed accounts. A growing number of firms have gone public, enabling shareholders to get exposure to alternative investing without investing in their funds. Meanwhile, there is a range of derivative instruments on listed private equity, including exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

As important as these structural changes in the alternative investment arena are, the most common form of investing in private equity and real assets remains the limited partnership. In a limited partnership, investors serve as limited partners (LPs) committing capital to a fund, which is raised and managed by a general partner (GP). Such limited partnership funds typically have a lifespan of 10 years, with the possible extension of 2 years. For this period, LPs essentially lock in their capital, notwithstanding the emergence of a secondary market in recent years. At any given point in time, LPs have to be in a position to respond to capital calls by the GP, subjecting fund investments to significant funding risk.

Unfortunately, studies on managing illiquidity risk associated with investments in limited partnerships have remained rare. This may seem surprising in light of the growing importance of private equity and real assets in investors' portfolios and the experience of several LPs in the recent global financial crisis. It is therefore the objective of this book to narrow this gap by developing risk management guidelines drawing upon best practices.

1.3 ORGANIZATION OF THE BOOK

This book is organized in three parts. In Part I, we discuss illiquid investments in private equity and real assets from a market perspective. In Part II, we focus on risk measurement for portfolios of limited partnership funds targeting these asset classes. Finally, in Part III, we discuss some techniques for managing this risk and related issues.

1.3.1 Illiquid investments as an asset class

Our discussion starts by defining long-term assets that are subject to structural illiquidity, offering investors a risk premium. These assets constitute the universe of investment opportunities we address in this book, which have to be clearly distinguished from assets that may become temporarily illiquid in periods of financial turmoil. In Chapter 2, we provide an estimate of the size of the market for illiquid investments in private equity and real assets. These asset classes can be accessed through alternative routes, which, however, require strategy-specific risk management approaches. In contrast, limited partnerships provide a structural investment framework, which is largely agnostic with regard to the underlying asset class – presumably an important reason why limited partnerships have remained the dominant route for ...