- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

1611: Authority, Gender, and the Word in Early Modern England explores issues of authority, gender, and language within and across the variety of literary works produced in one of most landmark years in literary and cultural history.

- Represents an exploration of a year in the textual life of early modern England

- Juxtaposes the variety and range of texts that were published, performed, read, or heard in the same year, 1611

- Offers an account of the textual culture of the year 1611, the environment of language, and the ideas from which the Authorised Version of the English Bible emerged

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Jonson's Oberon and friends: masque and music in 1611

Bringing in the New Year

1611 began in England with a flourish of culture in the court of King James. On New Year's Day the King, his family, his courtiers and several foreign ambassadors attended the performance of a masque in the Banqueting House of his court at Whitehall. Masques were an integral part of courtly celebrations and central to the iconography of royalty by 1611; their plots often incorporated rebellious energies shown to be overcome by peaceful authority, and their mixture of drama, music, dance and visual splendour was a symbolic display of learning, largesse and patronage. The masque to mark the beginning of 1611, Oberon, The Faery Prince, was no exception: it was the result of collaborative work by some of the greatest creative artists active in England at the time. The text, which includes dialogue, lyric verse, stage directions, scenic descriptions and learned annotation, was written by Ben Jonson; the songs were set to music by Alfonso Ferrabosco the Younger, Prince Henry's music tutor; the performance took place in costumes and on stage sets designed by Inigo Jones; its speaking parts were played by members of Shakespeare's company, the King's Men; its lively action included ballets devised by choreographers Confesse, Giles and Herne, and it concluded with courtly dances to the music of Robert Johnson. The patron and central figure of this glittering event was James's elder son, Henry, whose political coming of age had been celebrated for much of 1610 and had kept many writers, including Samuel Daniel, very busy with masques and other ceremonial ‘solemnitie’ (Daniel (1610), title page). The festivities surrounding Henry's investiture as Prince of Wales may be seen as reaching their completion with this new-year masque for 1611, reminding us immediately of the continuity of cultural history in which the start of this special year simultaneously represents the continuation and climax of other cycles of events and experiences.

The full title of the masque also evokes the recent past in textual culture. The character of Oberon played a key role in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, in performance since the 1590s and available in print since 1600; Oberon also featured in Robert Greene's play, The Scottish Historie of James the Fourth … Entermixed with a Pleasant Comedie, presented by Oboram, King of Fayeries, staged in 1590 and published in 1598. The subtitle of Jonson's masque, identifying Oberon as the ‘Faery Prince’, was bound to call to mind a major work of recent English poetry, Spenser's The Faerie Queene, and with it, no doubt, positive memories of the reign of Elizabeth I and the glorious triumphs of her Protestant kingdom. It is perhaps no coincidence that the poetic works of Spenser, who had died in 1599, were collected and published in a grand folio volume during 1611. Jonson's new-year masque therefore asserts, even in its title and subtitle, that there is no such thing as a clean slate on which to create new texts: the new year and its products are built on the continuing cultural memories of the preceding era.

The title page of Oberon, as printed in Jonson's own folio Workes in 1616, announces the text as ‘A Masque of Prince Henries’, indicating the young prince's sponsorship of the event, and on 1 January 1611 it was Henry himself who played the title role of the ‘Faery Prince’. This early modern dramatic, musical and visual spectacle is a fitting place to begin our study of the textual culture of 1611 – not only because it was performed on the very first day of the year and is in itself a ‘minor masterpiece’ (Butler, 188) but also because it encapsulates the typically vital interconnections in this period between language, performance, politics and the moment. The simple plot – concerning a set of rebellious satyrs awaiting the arrival of Prince Oberon in their midst – focuses on excited anticipation: the dramatic impulse is forward-looking, intent upon the appearance of this splendid emblem of virtue and authority. The masque is preoccupied with time and is imbued from the start with a sense that the moment – aptly for a new year's celebration – must be seized. The spectacle opens with a night-time scene, described by Jonson as ‘nothing … but a darke Rocke, with trees beyond it; and all wildnesse, that could be presented’ (Jonson 7 (1941), 341). The first figure on stage is a ‘Satyre’, a mythological woodland creature whose presence and physical appearance, featuring ‘cloven feet’, ‘shaggie thighs’ and ‘stubbed hornes’ (345–6), would immediately suggest uncontrolled energies and excessive revelling. Although the emphasis is on ‘play’, it is already significant that there is an urgency about the Satyr's attempt to wake his playfellows with the sound of his cornet:

Come away,

Times be short, are made for play;

The hum'rous Moone too will not stay:

What doth make you thus delay?

(341)

The ‘hum'rous’ moon ‘will not stay’: its brief pre-eminence and its shifting cycles, like the changing humours or moods of human beings, suggest the necessity of haste in the interests of pleasure. The prince whom they hope to see, Oberon, is himself the head of the fairy realm and thus a monarch of the night: even he is constrained by time. The impact of the initial nocturnal scene upon those present on New Year's Day 1611 is recorded in the extant eyewitness account of the diplomat William Trumbull. He refers to the ‘great rock’, the brilliantly craggy form at the centre of Inigo Jones's set, and specifically notes that the moon was ‘showing above through an aperture, so that its progress through the night could be observed’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 522–3). The passing of time is thus made a part of the set's visual effects and, as the action proceeds, the audience is constantly reminded of the temporal nature of the experience: ‘O, that he so long doth tarrie’, cry the impatient Chorus as they wait for Oberon, and later much is made of the cock's crow, a sign of the coming end of the night and so the exact time for the Prince to emerge – he who fills ‘every season, ev'ry place’ with his ‘grace’, and in whose face ‘Beautie dwels’ (Jonson 7 (1941), 343).

When Oberon, played by Prince Henry, is pulled forward in a chariot at this crucial moment in the masque, his arrival is hailed by a song which reminds the audience that the ultimate purpose of the masque is the glorification not of Henry but of King James. The reason given for Oberon's visit is that he is to pay his ‘annuall vowes’ to the legendary King Arthur (Jonson 7 (1941), 352) in a new-year statement of homage. This is yet another way in which the masque is explicitly shaped by the significance of time, but it is also an assertion of the hierarchical authority celebrated by the performance. In the mythology of the drama, Oberon pays his respects to ‘ARTHURS chayre’, but the words of the song explicitly point out that there is only one monarch higher than King Arthur, and that is ‘JAMES’, the ‘wonder’ of ‘tongues, of eares, of eyes’ (351). Seated on his throne in pride of place above the audience at Whitehall, James is the off-stage focus of the nocturnal masque. As Jonson's text asserts, James is the glorious sun by whose reflected light the moon and her prince can shine:

The solemne rites are well begunne;

And, though but lighted by the moone,

They show as rich, as if the sunne

Had made this night his noone.

But may none wonder, that they are so bright,

The moone now borrowes from a greater light.

(354)

Through the mirroring effect of the masque's rhetoric and movement, in which the actions on stage are intimately bound up with the relationships in and with the audience, Oberon reasserts James's position as the rightful descendant of Arthur. Indeed, Trumbull's account of the one-off performance of the masque makes it clear that James's political concerns were prominent: the ‘very large curtain’ which hung in front of the set until the performance began was ‘painted with the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, with the legend above Separata locis concordi pace figantur’, meaning ‘May what is separated in place be joined by harmonious peace’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 522). James's regal identity was firmly associated with keeping war at bay – his personal motto was the biblical phrase Beati Pacifici [blessed are the peacemakers] – and one of the major priorities of his reign was to maintain the several kingdoms of the British Isles in relatively peaceful coexistence. In an allegory of James's political concerns, the factions and orders of the fairy world who appear in the masque – the playful satyrs at first, followed by the sylvans who guard Oberon's palace and the more elevated fays in the prince's entourage – are all reconciled in the action of the masque before the Prince and his company conclude the spectacle in paying homage to King James and Queen Anna on their dais. In Trumbull's words, at the conclusion of Oberon, ‘the masqueraders approached the throne to make their reverence to their Majesties’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 523), with the poetry of peaceful reconciliation and the graceful harmonies of the dance music ringing in their ears.

The Originality of Jonson's Oberon

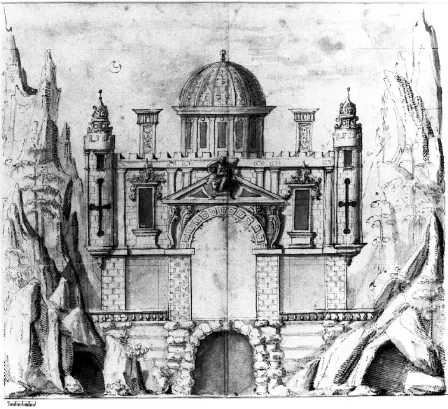

Appropriately, then, the satyrs and other lowly imaginary creatures are not banished from the concluding celebrations but are brought together, like the nations of James's kingdom, in order to pay due reverence to Oberon and, allied with him, to the king. Indeed, the whole thrust of the masque, in its temporal urgency, textual detail, personnel and performance, is towards unity. The masque as a genre brings together words and music, tableaux and movement, sight and sound, while Prince Henry united in his own person a Scottish dynasty, an English court and a Welsh title. The visual effects of Oberon similarly emphasise continuity and transformation rather than opposition. Whereas in most masques there is a firm contrast between the ‘anti-masque’ – a preliminary section emphasising disharmony – and the masque proper with its elegance and order, these differences are underplayed in Oberon. Inigo Jones's designs radically suggest inclusion rather than opposition: the rocks of the opening scene are not removed before the main action begins but instead open to reveal Oberon's palace within them (Figure 1). Jonson uses the term ‘discovery’ for this scene change, implying a process of uncovering or showing forth what has been present all along: ‘There the whole Scene opened, and within was discouer'd the Frontispice of a bright and glorious Palace, whose gates and walls were transparent’ (Jonson 7 (1941), 346). This fabulous second set is yet superseded by a third in which the ‘whole palace’ is fully opened and a ‘nation of Faies’ is also ‘discover'd’; deeper within the palace, the fairy knights are seen ‘farre off in perspectiue’ and finally, ‘at the further end of all’, Oberon himself is visible ‘in a chariot’ (351). The dramatic effect of this carefully staged spectacle evidently amazed the assembled company at Whitehall: Trumbull noted that ‘the rock opened discovering a great throne with countless lights and colours all shifting, a lovely thing to see’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 522). Only after this transformation of rugged rocks into dignified external architecture and decorative inner splendour is Oberon himself permitted to appear and move forward to the centre of the stage. His chariot is said to have been pulled by ‘two white beares’ (Jonson 7 (1941), 351), an exotic touch probably provided by the polar bears sent as a gift to James by the Muscovite Company and known to have been in the Bankside bear garden in London at this time (Ravelhofer, 203). In this detail, once again, unity and government are symbolised: the whole world – polar and temperate, nocturnal and diurnal, mythological and political – is brought together under James's rule.

Figure 1 Inigo Jones, design for the palace of the fairy prince in Ben Jonson's masque Oberon. Image from the Devonshire Collection, reproduced by kind permission of the Duke of Devonshire and the Chatsworth settlement. Photographic survey, Courtauld Institute of Arts.

The masque thus consciously displays the beneficence of royal patronage in bringing opposing forces into harmony. The satyrs, who threaten disorder within the kingdom, are not punished but reformed: ‘Though our forms be rough, & rude, / Yet our acts may be endew'd / With more vertue’ (Jonson 7 (1941), 351). These ‘rough’ creatures remain on stage until the end of the dances with which the masque concludes; they, too, witness the reconciling of darkness and light in the ‘brightnesse of this night’ (356). The reconciliation of a variety of traditions could even be seen in the design by Inigo Jones for Oberon's costume: Trumbull describes the armour of this peace-loving, almost Christ-like figure of grace and beauty as resembling that of the ‘Roman emperors’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 522), and Jones's sketch includes warlike leonine faces on the sleeve, breastplate and boots, linking Oberon with classical heroism as well as the aggressive energy of the satyrs. The physical impression made by the young prince in his role as Oberon must indeed have been splendid. His costume far outshone even those of his fairy entourage as Jones's design makes clear. Trumbull's report speaks of all the ‘gentlemen’ in the masque wearing ‘scarlet hose’, ‘white brodequins full of silver spangles’, ‘gold and suilver cloth’ and ‘very high white plumes’; however, whereas each of these fairy knights wore ‘a very rich blue band across the body’, Henry's band was ‘scarlet, to distinguish him from the rest’ (Jonson 10 (1950), 522). Since his role was a silent one – Henry was the focus of the spectacle and the dances but had no text to speak or sing – the Prince's visual presence in the masque was of crucial importance. The Venetian ambassador's report supplies evidence that Henry carried off his corporeal ceremonies and dancing with great success: ‘On Tuesday the Prince gave his Masque, which was very beautiful throughout, very decorative, but most remarkable for the grace of the Prince's every movement’ (CSP, 106).

Though the Prince does not speak a word in the course of the masque, and much of the impact of the work depends upon design, colour and music, the role of language in this entertainment should not be underestimated. Words are, in themselves, a recurring topic in the verse, as well as its medium. The leader of the unruly satyrs, Silenus, overhears two of them discussing the wooing of ‘Nymphes’ and immediately rebukes them:

Chaster language. These are nights

Solemne, to the shining rites

Of the Fayrie Prince, and Knights.

(Jonson 7 (1941), 343)

As Jonson's learned note to these lines points out, the classical Silenus shared none of the ‘petulance, and lightnesse’ of the other satyrs but ‘on the contrarie, all gravitie, and profound knowledge, of most secret mysteries’ (343). Nor does Jonson's Silenus share the rough language of his ‘wantons’, the shaggy satyrs (345); by contrast, Silenus is eloquent in his praise of Oberon and, pointedly, stresses the prince's own skill in the use of language. He likens Oberon to Mercury, the ‘god of tongue’ who was said to have wooed Penelope with winning words, and draws a parallel between Oberon and Apollo, the god who sang expressively to the accompaniment of his harp (344). Facility with language, the very basis of the textual culture with which 1611 is so rich, is already to be seen here as fundamental to the projected ideal of royalty. The King, who in Oberon is simultaneously both the Arthur of romance and the James of reality, is said to ‘teach’ his people ‘by the sweetnesse of his sway’, his persuasive rhetoric, ‘And not by force’ (353): language, literally, rules. Jonson himself is attentive to the craft of rhetoric in Oberon, and not least to the symbolic power of poetic metre. While the satyrs speak in shorter lines of verse, mainly trochaic, Jonson uses a more dignified iambic pentameter as the norm for the fairies' songs and dialogue. Nor are the words of the masque ignored or obscured when dressed in their musical settings. Ferrabosco's extant songs highlight the differences of style between the mythological beings: those with clay-like feet and ‘knottie legs’ (354) are given word settings with a somewhat plodding harmonic movement, while the supernatural quality of the fairies is aptly suggested by their more expressive and mellifluous melodies. In the setting of the song ‘Gentle Knights’, no listener could mistake the importance of the word ‘fairy’ with its melismatic melodic phrase rising across 12 different notes in a long smooth scale, or the upward leap to the highest note of the melody for the phrase ‘bright and airy’ (Chan, 236–7). The combination of words, music, movement, costumes and set is a triumph of expression and design.

One of the difficulties with a masque of this kind, linked to a specific moment in history, is that the special nuances of its occasion can never quite be recreated. We do have Jonson's extremely detailed text, with the printed dialogue centred on the page and encased in stage directions, description and annotation, which function almost as a textual staging, a printed impression of the perspectives and complexity of the genre (Ravelhofer, 206)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Chronology of Selected Historical, Cultural and Textual Events in 1611

- Introduction: ‘The omnipotency of the word’

- 1: Jonson's Oberon and friends: masque and music in 1611

- 2: Aemilia Lanyer and the ‘first fruits’ of women's wit

- 3: Coryats Crudities and the ‘travelling Wonder’ of the age

- 4: Time, tyrants and the question of authority: The Winter's Tale and related drama

- 5: ‘Expresse words’: Lancelot Andrewes and the sermons and devotions of 1611

- 6: The Roaring Girl on and off stage

- 7: ‘The new world of words’: authorising translation in 1611

- 8: Donne's ‘Anatomy’ and the commemoration of women: ‘her death hath taught us dearly’

- 9: Vengeance and virtue: The Tempest and the triumph of tragicomedy

- Conclusion: ‘This scribling age’

- Appendix: A List of Printed Texts Published in 1611

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 1611 by Helen Wilcox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.