eBook - ePub

Electrospinning

Materials, Processing, and Applications

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Electrospinning

Materials, Processing, and Applications

About this book

Electrospinning is from the academic as well as technical perspective presently the most versatile technique for the preparation of continuous

nanofi bers obtained from numerous materials including polymers, metals, and ceramics. Shapes and properties of fibers can be tailored

according to the demand of numerous applications including filtration, membranes, textiles, catalysis, reinforcement, or biomedicals.

This book summarizes the state-of-the art in electrospinning with detailed coverage of the various techniques, material systems and their

resulting fiber structures and properties, theoretical aspects and applications.

Throughout the book, the current status of knowledge is introduced with a critical view on accomplishments and novel perspectives. An

experimental section gives hands-on guidance to beginners and experts alike.

nanofi bers obtained from numerous materials including polymers, metals, and ceramics. Shapes and properties of fibers can be tailored

according to the demand of numerous applications including filtration, membranes, textiles, catalysis, reinforcement, or biomedicals.

This book summarizes the state-of-the art in electrospinning with detailed coverage of the various techniques, material systems and their

resulting fiber structures and properties, theoretical aspects and applications.

Throughout the book, the current status of knowledge is introduced with a critical view on accomplishments and novel perspectives. An

experimental section gives hands-on guidance to beginners and experts alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Fibers – Key Functional Elements in Technology and Nature

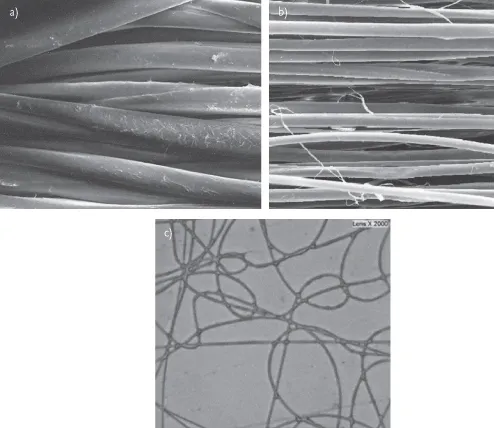

A multitude of objects surrounding us at home, an impressive number of technical parts controlling our day to day life both privately and in technical areas, even a set of currently emerging technologies have fibers as their basic structural and functional elements or depend at least on fiber-type architectures. A fiber is of course first of all a geometric shape, a 1Dimensional object, having a certain diameter, a given axial ratio and a certain length that can often approach infinity. Figure 1.1a displays a silk fiber as one example and Figure 1.1b a synthetic polyamide fiber as another example. Such fibers may not only be straight but might also display a certain curvature, they may be bent to some extent (Figure 1.1c).

Figure 1.1 SEM images of (a) silk fibers, (b) polyamide fibers, (c) optical image of polyamide fibers displaying curvature.

However, for real applications fibers have to be more than just geometrical elements. They have to fulfill a set of requirements, to display a selection of specific properties, of dedicated functions.

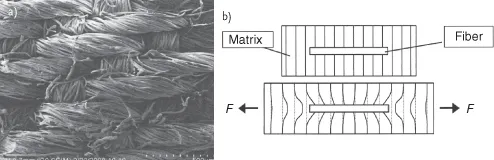

Textiles, produced, for instance, on the basis of synthetic polymer fibers not only allow us to dress up, to catch the eye of our fellow people, to display fancy dressings but they provide in many instances protection against cold temperatures, rain, strong winds, maybe in certain cases even against UV-radiation. In clothing the geometric features of the fibers enable the design, the preparation of planar textiles via weaving, knitting processes. These textiles are highly porous, as shown by the SEM image displayed in Figure 1.2a, thus controlling thermal insulation, wind resistance, passage of vapor emerging from the body such as sweat. In addition, the fibers have to be able to adsorb vapors and release them again in textile applications, they have to provide certain mechanical properties defined by particular magnitudes of fiber stiffness and strength, elasticity allowing for textile deformations that arise when using them as clothing and they should allow, for instance, to incorporate dyes, and pigments.

Figure 1.2 (a) SEM image of cotton textile, (b) fiber reinforcement, schematically showing fibers and stress lines; upper image: unstressed, lower image: stressed.

Transportation industries involved in building and using airplanes, rapid trains, automobiles and boats rely strongly on large-scale technical parts having an extremely low weight while displaying simultaneously a high stiffness and strength. Fibers are incorporated for this purpose into matrix materials such as polymers or ceramics, giving rise to mechanical reinforcement effects (Figure 1.2b).

Optical information technology comprising the transportation, manipulation and display of information by optical means not only in local areas as in a car but also on a larger scale within buildings, all the way to covering huge distances existing between continents depend heavily on optical fibers composed of inorganic or organic glasses. It is obvious that the fibers not only have to possess in this case a very high optical clarity, that is, a very high optical transmission, that they should be flexible so that they can be subjected to bending to be integrated into technical parts, but they also should have intrinsic optical guiding properties allowing for particular optical propagation modes. Electric cables transporting electric energy, air filters or fluid filters composed of fibers and providing for clean air, water, gasoline are further technical examples of objects, devices containing and relying on fibers as key elements. Furthermore, fibers are also basic ingredients in carpets, ropes, tapestry and this list can be extended endlessly with some fantasy involved.

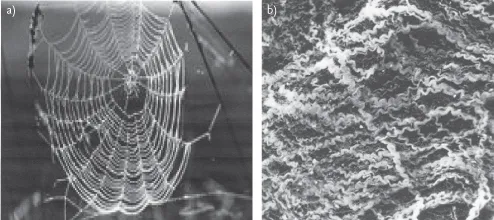

Fibers are, of course, not an invention of mankind, of modern techniques. Nature in fact has been using fibers as basic elements on a large scale to construct functional objects for millennia. Spider webs as displayed in Figure 1.3a obvious already to the naked eye and designed to catch insects are composed of a very loose network of intricate design to make them light, to offer a large cross-sectional area and yet to make them resistant to wind, storm, rain and to the attack of the prey trying to free itself. In terms of applications spider webs may serve as model structures for particular kinds of plant-protection devices, to be discussed later in more detail. Pheromone dispensers shaped along the architecture of spider webs and incorporating the enhanced mechanical properties of the basic fiber-like building elements offer significant advantages, as will be discussed later in some detail in Chapter 8.

Figure 1.3 (a) Spider web constructed from fibers, (b) extracellular matrix (ECM) surrounding cells in living tissue, composed of fibrils, for details see text.

A further example from nature characterized by a network of fibers in the nanometer range is the extracellular matrix (ECM), depicted in Figure 1.3b, which is an important 1D structured component of tissue. It has a broad range of tasks to accomplish. It embeds the cells of which the particular tissue is composed, it offers points of contacts to them, provides for the required mechanical properties of the tissue. Depending on the type of tissue the fibers are either tightly packed and oriented along a given direction, as in the case of muscles or are unoriented in a plane. as for instance in skin tissues. The first types of tissues require an enhanced mechanical strength in one particular direction, whereas the second one should be able to sustain planar stresses in all directions.

Finally, fibers such as wool fibers, hairs, silk fibers protect human beings and animals in a way similar to artificial clothing. They again possess specific mechanical properties, insulation properties and are able to adsorb moisture to a significant extent. Many more examples from nature come to mind, yet the aspect of fibers coming from nature will be kept short here since this topic will be revisited.

An obvious conclusion at this stage is that fibers are highly valuable and highly functional objects in technical and life science areas. However, it is important to point out that such fibers will in general not perform well in applications if one just chooses the right geometry, if one just focuses on them as geometric 1D objects. A first important aspect is the choice of the material with a given well-known set of mechanical, optical, electrical, thermal, or perhaps also magnetic properties, from which to produce the fibers. So, depending on the kind of application in view polymers, metals, inorganic materials will be selected as basic materials for the production of fibers. Yet, the well-known and tabulated general intrinsic properties of these materials are just guidelines, merely starting points for design considerations. More important is a tailored control of the intrinsic structure of the fiber via appropriate fiber preparation techniques to come up with the required advanced properties, functions aiming at the target application.

Fiber design thus requires in any case a very fundamental understanding of the correlation between the intrinsic structure of a fiber on the one hand and its properties, functions on the other side. Fiber design requires, furthermore, also the knowledge of how particular fiber-characteristic intrinsic structures can be achieved via the selection of appropriate fiber processing techniques and via the choice of suitable processing parameters. Finally, of course, one has to have a fundamental understanding on how to construct technical elements from fibers, on how to select the best architectures for them, and how to achieve particular functions in this way.

1.2 Some Background Information

1.2.1 Structure of Crystalline and Amorphous Materials

A basic first step towards fiber design for a particular application involves, as pointed out above, the selection of the material with a given spectrum of properties from which the fiber will be produced. A macroscopic piece of matter composed, for instance, of a metal such as copper or iron, of a glass being of inorganic or organic nature, of a semiconductor such as GaAs, or of a synthetic polymer such as poly (methyl methacrylate) displays a set of characteristic structural features and properties as controlled by the nature of the atoms/molecules of which they are composed, by the arrangement of these basic structural units in space as well as by the type of interactions existing between these units. Depending on the material under consideration various types of spatial arrangements of the atoms/molecules are experienced.

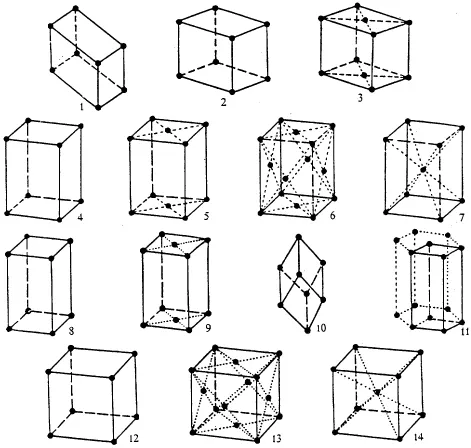

Crystalline materials are characterized by a highly regular 3D arrangement of the constituent atoms or molecules on a lattice in space displaying a translational symmetry. A so-called long-range order exists, that is, the position of the atoms/molecules far away from a reference atom/molecule is well defined as a function of the interatomic/intermolecular distances. This fact allows us to represent the crystalline structure in terms of the unit cell that is, the smallest element containing all structural features of the macroscopical crystal. As detailed in books concerned with crystallography, space-filling requirements lead to the conclusion that only certain types of lattice types – 14 Bravais lattices – should exist with cubic, hexagonal or triclinic lattices being some examples, as shown in Figure 1.4. In addition to the translational symmetry point symmetries are used to characterize the packing of the atoms, molecules making up the crystal in space. These lattices are displayed without exception by all types of materials able to crystallize including polymers.

Figure 1.4 14 Bravais lattices arising from symmetry considerations and displayed by all types of materials able to crystallize including polymers.

Based on such symmetry considerations predictions can be made on the anisotropy of properties – properties are different along different crystal axes – as well as on the presence of particular properties. Taking as an example the absence of an inversion center one can directly conclude that such a material can, in principle, display properties such a ferroelectricity, piezoelectricity or second-order nonlinear optical effects.

Considering briefly fibers one situation to be discussed later in more detail may well be that fibers prepared from one and the same material may display quite different properties, the reason being that fibers were produced in which different type of crystal modifications with different crystal unit cell occur, or in which different crystal unit-cell directions point along the fiber axis. It is also conceivable that fiber formation goes along with the introduction of specific crystals defects.

In contrast to crystalline structures, amorphous structures including glasses and melts do not display a regular packing of atoms, molecules in space, only a short-range order exists. This term represents the situation that the atoms or molecules are closely packed in an irregular manner so that one has only knowledge of the probabilities with which neighboring atoms/molecules occur as a function of the interatomic/intermolecular distance. The average distance to next and second-next neighbors is known within limits but no information is available for distances larger than these. Pair correlation functions are used to represent this situation again, as detailed in books on material science. Due to the particular kind of atomic or molecular packing amorphous materials in general display isotropic properties, that is, the properties along different directions of a piece of material will be equal. No optical birefringence is displayed by such structures, in contrast to the case of crystalline materials.

However, the situation might be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Nature of the Electrospinning Process – Experimental Observations and Theoretical Analysis

- 3 Nanofiber Properties

- 4 Nonwovens Composed of Electrospun Nanofibers

- 5 Electrospinning – Some Technical Aspects

- 6 Modification of the Electrospinning Technique

- 7 Materials Considerations

- 8 Technical Applications of Electrospun Nanofibers

- 9 Medicinal Applications for Electrospun Nanofibers

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Electrospinning by Joachim H. Wendorff,Seema Agarwal,Andreas Greiner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.