- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Astronomy and Cosmology

About this book

Introduction to Astronomy & Cosmology is a modern undergraduate textbook, combining both the theory behind astronomy with the very latest developments. Written for science students, this book takes a carefully developed scientific approach to this dynamic subject. Every major concept is accompanied by a worked example with end of chapter problems to improve understanding

- Includes coverage of the very latest developments such as double pulsars and the dark galaxy.

- Beautifully illustrated in full colour throughout

- Supplementary web site with many additional full colour images, content, and latest developments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to Astronomy and Cosmology by Ian Morison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Astronomy & Astrophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Astronomy, an Observational Science

1.1 Introduction

Astronomy is probably the oldest of all the sciences. It differs from virtually all other science disciplines in that it is not possible to carry out experimental tests in the laboratory. Instead, the astronomer can only observe what he sees in the Universe and see if his observations fit the theories that have been put forward. Astronomers do, however, have one great advantage: in the Universe, there exist extreme states of matter which would be impossible to create here on Earth. This allows astronomers to make tests of key theories, such as Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. In this first chapter, we will see how two precise sets of observations, made with very simple instruments in the sixteenth century, were able to lead to a significant understanding of our Solar System. In turn, these helped in the formulation of Newton’s Theory of Gravity and subsequently Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity – a theory of gravity which underpins the whole of modern cosmology. In order that these observations may be understood, some of the basics of observational astronomy are also discussed.

1.2 Galileo Galilei’s proof of the Copernican theory of the solar system

One of the first triumphs of observational astronomy was Galileo’s series of observations of Venus which showed that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the centre of the Solar System so proving that the Copernican, rather than the Ptolemaic, model was correct (Figure 1.1).

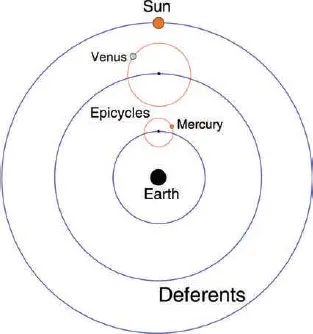

In the Ptolemaic model of the Solar System (which is more subtle than is often acknowledged), the planets move around circular ‘epicycles’ whose centres move around the Earth in larger circles, called deferents, as shown in Figure 1.2. This enables it to account for the ‘retrograde’ motion of planets like Mars and Jupiter when they appear to move backwards in the sky. It also models the motion of Mercury and Venus. In their case, the deferents, and hence the centre of their epicycles, move around the Earth at the same rate as the Sun. The two planets thus move around in circular orbits, whose centres lie on the line joining the Earth and the Sun, being seen either before dawn or after sunset. Note that, as Mercury stays closer to the Sun than Venus, its deferent and epicycle are closer than that of Venus – in the Ptolemaic model, Mercury is the closest planet to the Earth!

Figure 1.1 Galileo Galilei: a portrait by Guisto Sustermans. Image: Wikipeda Commons.

Figure 1.2 The centre points of the epicycles for Mercury and Venus move round the Earth with the same angular speed as the Sun.

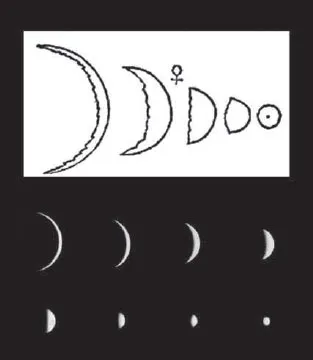

In the Ptolemaic model, Venus lies between the Earth and the Sun and hence it must always be lit from behind, so could only show crescent phases whilst its angular size would not alter greatly. In contrast, in the Copernican model Venus orbits the Sun. When on the nearside of the Sun, it would show crescent phases whilst, when on its far side but still visible, it would show almost full phases. As its distance from us would change significantly, its angular size (the angle subtended by the planet as seen from the Earth) would likewise show a large change.

Figure 1.3 shows a set of drawings of Venus made by Galileo with his simple refracting telescope. They are shown in parallel with a set of modern photographs which illustrate not only that Galileo showed the phases, but that he also drew the changing angular size correctly. These drawings showed precisely what the Copernican model predicts: almost full phases when Venus is on the far side of the Sun and a small angular size coupled with thin crescent phases, having a significantly larger angular size, when it is closest to the Earth.

Galileo’s observations, made with the simplest possible astronomical instrument, were able to show which of the two competing models of the Solar System was correct. In just the same way, but using vastly more sophisticated instruments, astronomers have been able to choose between competing theories of the Universe – a story that will be told in Chapter 9.

Figure 1.3 Galileo’s drawings of Venus (top) compared with photographs taken from Earth (bottom).

1.3 The celestial sphere and stellar magnitudes

Looking up at the heavens on a clear night, we can imagine that the stars are located on the inside of a sphere, called the celestial sphere, whose centre is the centre of the Earth.

1.3.1 The constellations

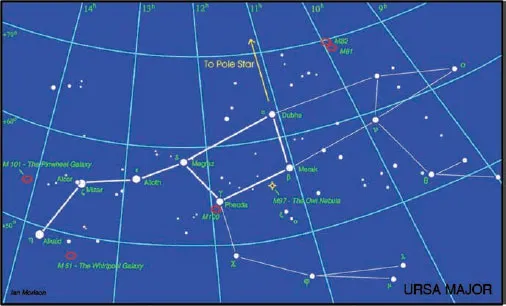

As an aid to remembering the stars in the night sky, the ancient astronomers grouped them into constellations; representing men and women such as Orion, the Hunter, and Cassiopeia, mother of Andromeda, animals and birds such as Taurus the Bull and Cygnus the Swan and inanimate objects such as Lyra, the Lyre. There is no real significance in these stellar groupings – stars are essentially seen in random locations in the sky – though some patterns of bright stars, such as the stars of the ‘Plough’ (or ‘Big Dipper’) in Ursa Major, the Great Bear, result from their birth together in a single cloud of dust and gas.

The chart in Figure 1.4 shows the brighter stars that make up the constellation of Ursa Major. The brightest stars in the constellation (linked by thicker lines) form what in the UK is called ‘The Plough’ and in the USA ‘The Big Dipper’, so called after the ladle used by farmers’ wives to give soup to the farmhands at lunchtime. On star charts the brighter stars are delineated by using larger diameter circles which approximates to how stars appear on photographic images. The grid lines define the positions of the stars on the celestial sphere as will be described below.

Figure 1.4 The constellation of Ursa Major – the Great Bear.

1.3.2 Stellar magnitudes

The early astronomers recorded the positions of the stars on the celestial sphere and their observed brightness. The first known catalogue of stars was made by the Greek astronomer Hipparchos in about 130–160 BC. The stars in his catalogue were added to by Ptolomy and published in 150 AD in a famous work called the Almagest whose catalogue listed 1028 stars. Hipparchos had grouped the stars visible with the unaided eye into six magnitude groups with the brightest termed 1st magnitude and the faintest, 6th magnitude. When accurate measurements of stellar brightness were made in the nineteenth century it became apparent that, on average, the stars of a given magnitude were approximately 2.5 times brighter than those of the next fainter magnitude and that 1st magnitude stars were about 100 times brighter than the 6th magnitude stars. (The fact that each magnitude difference showed the same brightness ratio is indicative of the fact that the human eye has a logarithmic rather than linear response to light.)

In 1854, Norman Pogson at Oxford put the magnitude scale on a quantitative basis by defining a five magnitude difference (i.e., between 1st and 6th magnitudes) to be a brightness ratio of precisely 100. If we define the brightness ratio of one magnitude difference as R, then a 5th magnitude star will be R times brighter than a 6th magnitude star. It follows that a 4th magnitude star will be R × R times brighter than a 6th magnitude star and a 1st magnitude star will be R × R × R × R × R brighter than a 6th magnitude star. However, by Pogson’s definition, this must equal 100 so R must be the 5th root of 100 which is 2.512.

The brightness ratio between two stars whose apparent magnitude differs by one magnitude is 2.512.

Having defined the scale, it was necessary to give it a reference point. He initially used Polaris as the reference star, but this was later found to be a variable star and so Vega became the reference point with its magnitude defined to be zero. (Today, a more complex method is used to define the reference point.)

1.3.3 Apparent magnitudes

It should be noted that the observed magnitude of a star tells us nothing about its intrinsic brightness. A star that appears bright in the sky could either be a faint star that happens to be very close to our Sun or a far ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Author’s Biography

- Chapter 1: Astronomy, an Observational Science

- Chapter 2: Our Solar System 1 – The Sun

- Chapter 3: Our Solar System 2 – The Planets

- Chapter 4: Extra-solar Planets

- Chapter 5: Observing the Universe

- Chapter 6: The Properties of Stars

- Chapter 7: Stellar Evolution – The Life and Death of Stars

- Chapter 8: Galaxies and the Large Scale Structure of the Universe

- Chapter 9: Cosmology – the Origin and Evolution of the Universe

- Index