![]()

CHAPTER 1

Buffett and the Fundamental Business Perspective

He doesn’t gamble in the stock market; he doesn’t take short-term, technical positions betting on immediate spikes or dips. He is not a buy-and-hold mutual fund investor. Warren Buffett is a long-haul business investor who takes partial, if not whole, positions in companies with favorable underlying economics, good management, and consumer monopolies.

Warren Buffett as Your Small Business Consultant

To draw a quick distinction between a Buffett-style investment and one that is not, ask yourself this question: “In 20 years, is it more likely that consumers will be drinking Coke or using the iPhone?” This question is not designed to play favorites. It is meant to illustrate the guts of the Warren Buffett investment methodology, and if you can understand the reasoning behind the answer, you will be well on your way to building a small business that Warren Buffett would love. In 20 years, is it more likely that consumers will be drinking Coke or using the iPhone?

I choose Coke … why? First, four prima facie answers:

1. The company has been building its brand since 1886.1

2. A can, bottle, or fountain Coke is always within about a 100-yard reach of every human being on the planet regardless of location.

3. The company had $35 billion in sales last year.2

4. Every time I go to the movies, I see a Coke commercial. (Amazingly enough, although polar bears can swim up to 100 miles at a stretch, they are very awkward, lumbering walkers and must kill their prey by resting silently outside of breathing holes in the ice. Even more amazing is the fact that they have enough dexterity in their goofy paws to twist off bottle caps.)

And here are five financial answers that Warren Buffett loves:

1. Outside of a few blips on the radar, the company has had increasing and steady earnings over the past 10 years.

2. The earnings per share have grown at an approximate rate of 13.65 percent over the same period,

3. The return on equity has averaged 32 percent over the past 10 years.

4. The company could pay off its long-term debt in about one year, strictly from earnings.3

5. The company can adjust its prices to inflation. In 1950 a bottle of Coke cost a nickel.4 Today, depending on location, a Coke will cost anywhere from one to two dollars.

The answer to our question and subsequent analysis is not a comment on the viability of Apple or a statement on the quality of the product. Apple is a highly innovative company with outstanding, mind-numbing products. The intention of the answer is to place an emphasis on the predictability of a company. No one can predict the future, but if an attempt must be made (that is, we are building a business that needs to be successful in the future), is it more likely that an accurate prediction can be made based on a rock-solid, consistent track record or on one that is questionable? Not that Apple does not have a strong track record, but guess what, Coke’s is stronger. Plus, you are already taking the bet. It’s a moot point to say I wouldn’t take either one since you are already putting your chips on the table whether by stock purchase, rental property investment, or building a small business that Warren Buffett would love. Since you are joining the party, make sure it is a fun one by taking the surer bet.

Many will argue that past results are not an indicator of future performance, but in the case of Warren Buffett’s track record, much of his success can be attributed to a mold of key historic attributes. These attributes, when modeled after in a small business, can lead to great results.

Return on Equity, Return on Investment—the Preview

For any investment decision, whether it be the purchase of a fourplex or the launch of a small business, it is important to calculate the investment’s return on investment and return on equity in order to determine if we have a stinker or a winner. (Why would I buy into an investment that churns out a 5 percent return when I can get 10 percent down the road at the local investment farmer’s market?) Return on investment is found simply by dividing the business’s earnings by the initial investment, whereas return on equity is the earnings divided by the equity in the business found on the balance sheet. These ratios are crucial for investment purposes—crucial, I tell you!

For example: Your business, a hamburger stand, let’s call it Sloppy Joe’s, consistently generates $10,000 a year in earnings on an initial $50,000 investment for a return on investment of 20 percent. You peer into the feasibility of a second location and determine that Sloppy Joe’s Too will generate $1,000 a year in earnings on top of a $25,000 investment for a 4 percent rate of return. A quick Google search reveals that risk-free Treasury bills are paying approximately 4.7 percent,5 a return slightly higher than the 4 percent that would be churned out by SJ2. The optimal investment decision would be to take the T-bills and not the second location. If you discover another expansion opportunity yielding a return greater than or equal to 20 percent, all things equal, it would be financially prudent to pursue the new opportunity. Honestly, it would be financially prudent to pursue any opportunity that is greater than the return you can get in the next best investment. If you can get 15 percent in the market, then you have to beat 15 percent.

Both rate of return and return on equity can be used to compare investments across asset classes. For example: A dividend-paying stock yielding a 7 percent rate of return for the year is inferior to a rental property returning 15 percent a year, all else equal. A business generating a 4 percent rate of return is inferior to a stock yielding a 6 percent return and, a rental property spewing out a 10 percent return is inferior to a stock that grows in value by 15 percent a year. Got it?

Apples to Apples

A rental duplex cash flow of $5,000 a year on top of a $50,000 investment is providing a 10 percent rate of return (by the way, rate of return and return on investment are the same thing), which is a superior investment compared to a duplex cash flow of $7,000 a year on top of a $100,000 investment for a 7 percent return.

A stock consistently delivering an average 20 percent return on equity, in Warren Buffett’s opinion, is in essence delivering a 20 percent rate of return. He claims this return as his (more on this later). A dividend stock paying an annual yield of $.70 with an average price of $10 a share is delivering a 7 percent rate of return. A business with $20,000 in earnings for the year and an initial investment of $100,000 is yielding 20 percent.

In the world of small business and investing, rate of return (return on investment) reigns supreme.

Investing from the Business Perspective

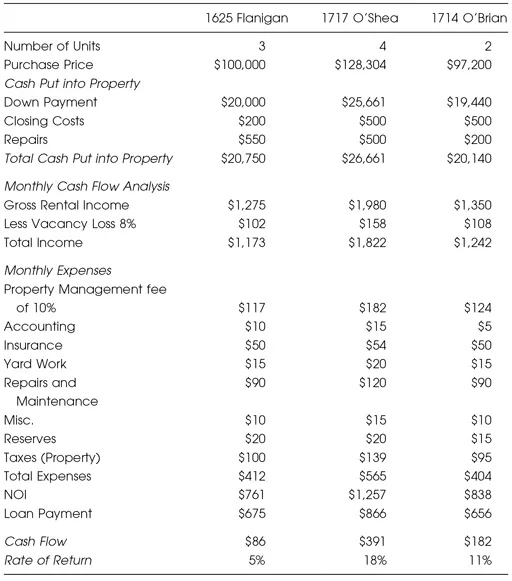

To further illustrate rate of return and how it applies across investments including small business, let us step into the shoes of a rental property investor. A true rental property investor evaluates property based on cash flow and the rate of return. The following table details a cash flow analysis of three sample rental properties, a triplex, fourplex, and duplex respectively. The combination of a down payment, closing costs, and repairs equals the total down payment needed to invest in each of the three properties. These figures are culled from real deals, so don’t accuse me of making up some hokey numbers. See Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Cash Flow Analysis

The cash flow analysis works as follows: The rental income comes in the door, then operational expenses such as vacancy loss, property management fees, accounting, yard work, and repair and maintenance expenses peck away, and what remains is the net earnings or, in a cash budget, the cash flow. In order to calculate the rate of return, annualize the cash flow by multiplying by 12 and dividing by the total property investment, which in this case is $20,750, $26,661, and $20,140 respectively. This results in a 5 percent, 18 percent, and 11 percent rate of return for each of the properties. All things equal, the property with the 18 percent rate of return is the superior investment.

Warren Buffett applies the same logic to his investment decisions. If he buys a share of stock for $50 and it generates $5 in earnings per share, his initial rate of return is 10 percent. ($5/$50).6 As the earnings of the company grow, so does the return over time.

This analysis, as used by the rental investor and the Buffett investor, or the hybrid Brental investor, should be the same analysis utilized by the small business owner: A hamburger stand generating $20,000 of yearly earnings on top of a $100,000 investment is generating a 20 percent rate of return. Compared to Treasury bonds, currently yielding approximately 3.5 percent, this is a superior investment.

This, in a nutshell, is investing and building a business via a business perspective.

A Spiel on Capital Gains

Cash flow investors traditionally seek out timely, systemic payments from their assets. For example: A dividend stock investor expects a quarterly dividend payment, a rental property investor seeks a monthly check, a covered call writer often generates income at least once a month. A cash flow investor works for cash flow first and lets capital gains serve as the icing on the cake. If a rental property generates 15 percent a year in cash flow and the property appreciates an additional 4 percent a year, then so be it. The question that cash flow investors traditionally seek to answer is: “Can I pay my monthly bills from cash flow?” If the answer is yes, then the cash flow investor claims financial independence and typically Yahtzee!

The cash flow paradigm is contrasted with that of the capital gains investor. The capital gains investor invests for appreciation of the underlying asset; an asset is purchased for $1 in hope that it will go up to $10, for example. A property capital gains investor will buy a piece of real estate, banking on the appreciation and cashing out at the end, or he will seek to fix and flip the property over the short term. In this way, investors do not necessarily receive monthly cash flow; they can cleave off the capital gains to create a “cash flow,” and as long as they do not dip into the principal they have a cash flowing system, although this cleaving will result in a capital gains tax.

Warren Buffett, on the other hand, buys outstanding companies with phenomenal rates of return that continue to reinvest this return and greatly increase the value of the company.

Turning Capital Gains into Cash Flow

Thus, it can be argued that capital gains is essentially “cash flow”; it is just received in larger chunks via systematic withdraws. Mutual fund investors are the best example of this format. A mutual fund investor can theoretically cash out the average gain received on a timely basis, treating it as cash flow. If an individual is banking on an average yearly return of 15 percent, then in theory the investor can cash out 15 percent a year without decreasing the principal. An investor with a $100,000 mutual fund investment, in this example, is counting on $15,000 a year. The problem, of course, lies in the dips. The stock market may average 10 percent over the long run, but some years it may do 20 percent and some ...