- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this comprehensive yet compact monograph, Michel W. Barsoum, one of the pioneers in the field and the leading figure in MAX phase research, summarizes and explains, from both an experimental and a theoretical viewpoint, all the features that are necessary to understand and apply these new materials. The book covers elastic, electrical, thermal, chemical and mechanical properties in different temperature

regimes. By bringing together, in a unifi ed, self-contained manner, all the information on MAX phases hitherto only found scattered in the journal literature, this one-stop resource offers researchers and developers alike an insight into these fascinating materials.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access MAX Phases by Michel W. Barsoum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

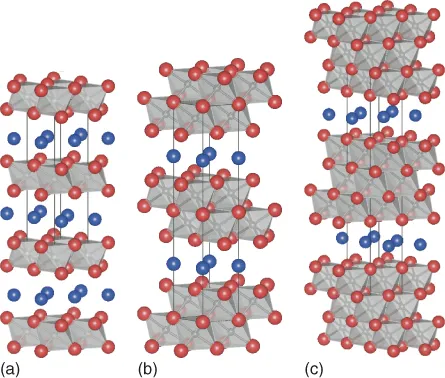

The Mn+1AXn, or MAX, phases are layered, hexagonal, early transition-metal carbides and nitrides, where n = 1, 2, or 3 “M” is an early transition metal, “A” is an A-group (mostly groups 13 and 14) element, and “X” is C and/or N. In every case, near-close-packed M layers are interleaved with layers of pure group-A element with the X atoms filling the octahedral sites between the former (Figure 1.1a–c). The M6X octahedra are edge-sharing and are identical to those found in the rock salt structure. The A-group elements are located at the center of trigonal prisms that are larger than the octahedral sites and thus better able to accommodate the larger A atoms. The main difference between the structures with various n values (Figure 1.1a–c) is in the number of M layers separating the A layers: in the M2AX, or 211, phases, there are two; in the M3AX2, or 312, phases there are three; and in the M4AX3, or 413, phases, there are four. As discussed in more detail in later chapters, this layering is crucial and fundamental to understanding MAX-phase properties in general, and their mechanical properties in particular. Currently, the MAX phases number over 60 (Figure 1.2) with new ones, especially 413s and solid solutions, still being discovered.

Figure 1.1 Atomic structures of (a) 211, (b) 312, and (c) 413 phases, with emphasis on the edge-sharing nature of the MX6 octahedra.

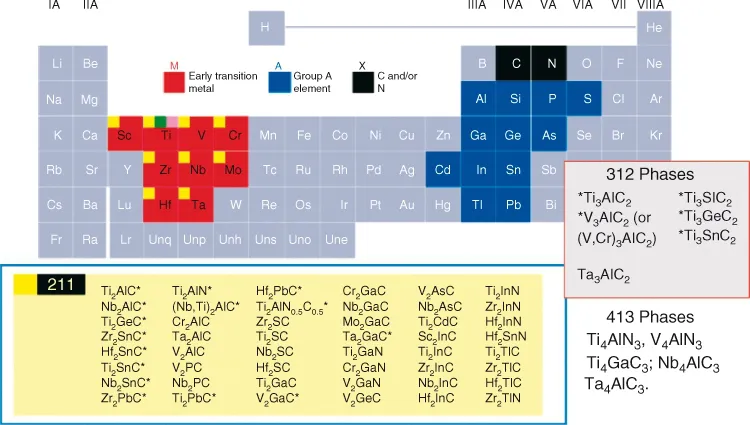

Figure 1.2 List of known MAX phases and elements of the periodic table that react to form them.

Most of the MAX phases are 211 phases, some are 312s, and the rest are 413s. The M group elements include Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, and Ta. The A elements include Al, Si, P, S, Ga, Ge, As, Cd, In, Sn, Tl, and Pb. The X elements are either C and/or N.

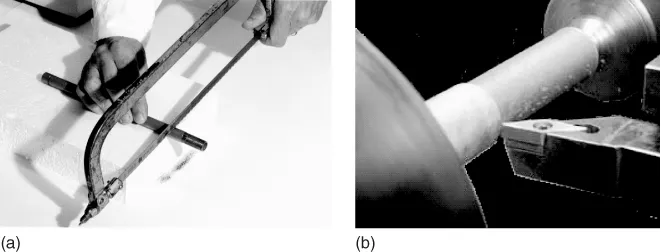

Thermally, elastically, and electrically, the MAX phases share many of the advantageous attributes of their respective binary metal carbides or nitrides: they are elastically stiff, and electrically and thermally conductive. Mechanically, however, they cannot be more different: they are readily machinable – remarkably a simple hack-saw will do (Figure 1.3) – relatively soft, resistant to thermal shock, and unusually damage-tolerant. They are the only polycrystalline solids that deform by a combination of kink and shear band formation, together with the delaminations of individual grains. Dislocations multiply and are mobile at room temperature, glide exclusively on the basal planes, and are overwhelmingly arranged either in arrays or kink boundaries. They combine ease of machinability with excellent mechanical properties, especially at temperatures >1000 °C. Some, such as Ti3SiC2 and Ti4AlN3, combine mechanical anisotropy with thermal properties that are surprisingly isotropic.

Figure 1.3 One of the hallmarks of the MAX phases is the ease with which they can be machined with (a) a manual hack-saw and (b) lathe.

As discussed in this book, this unusual combination of properties is traceable to their layered structure, the mostly metallic – with covalent and ionic contributions – nature of the MX bonds that are exceptionally strong, together with M–A bonds that are relatively weak, especially in shear. The best characterized ternaries to date are Ti3SiC2, Ti3AlC2, and Ti2AlC. We currently know their compressive and flexural strengths and their temperature dependencies, in addition to their hardness, oxidation resistance, fracture toughness and R-curve behavior, and tribological properties. Additionally, their electrical conductivities, Hall and Seebeck coefficients, heat capacities (both at low and high temperatures), elastic properties and their temperature dependencies, thermal expansions, and thermal conductivities have been quantified.

1.2 History of the MAX Phases

The MAX phases have two histories. The first spans the time they were discovered in the early and mid-1960s to roughly the mid-1990s, when, for the most part, they were ignored. The second is that of the last 15 years or so, when interest in these phases has exploded. Table 2.2 lists the first paper in which each of the MAX phases was first reported.

1.2.1 History Before 1995

Roughly 40 years ago, Nowotny published a review article (Nowotny, 1970) summarizing some of the work that he and his coworkers had carried out during the 1960s on the syntheses of a large number of carbides and nitrides. It was an impressive accomplishment; during that decade, his group discovered over 100 new carbides and nitrides. Amongst them were more than 30 Hägg phases which are of specific interest to this work. These phases, also called H-phases – but apparently not after Hägg (Eklund et al., 2010) – had the M2AX chemistry (Figures 1.1a and 1.2).

The history of the H-phases, henceforth referred to as 211s, before 1997 is short. Surprisingly, from the time of their discovery until our first report (Barsoum, Brodkin, and El-Raghy, 1997) – and apart from four Russian papers in the mid-1970s (Ivchenko and Kosolapova, (1975, 1976); Ivchenko et al., 1976a,b) in which it was claimed that 90–92% dense compacts of Ti2AlC and Ti2AlN were synthesized – they were totally ignored. The early Russian results have to be interpreted with caution as their reported microhardness values of ≈21–24 GPa are difficult to reconcile with the actual values, which range from 3 to 4 GPa. Some magnetic permeability measurements on Ti2AlC and Cr2AlC were also reported in 1966 (Reiffenstein, Nowotny, and Benesovsky, 1966).

In 1967, Nowotny's group discovered the first two 312 phases, Ti3SiC2 (Jeitschko and Nowotny, 1967) and Ti3GeC2 (Wolfsgruber, Nowotny, and Benesovsky, 1967), both of which are structurally related to the H-phases in that M3X2 layers now separate the A layers (Figure 1.1b). It was not until the early 1990s, however, that Pietzka and Schuster, the latter a student of Nowotny's, added Ti3AlC2 to the list (Pietzka and Schuster, (1994, 1996)).

The history of Ti3SiC2 is slightly more involved. The first hint that Ti3SiC2 was atypical came as early as 1972, when Nickl, Schweitzer, and Luxenberg (1972) working on single crystals grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) showed that Ti3SiC2 was anomalously soft for a transition-metal carbide. The hardness was also anisotropic, with the hardness normal to the basal planes being roughly three times that parallel to them. When the authors used a solid-state reaction route, the resulting material was no longer “soft.” In 1987, Goto and Hirai (1987) confirmed the results of Nickl et al. A number of other studies on CVD-grown films also exist (Fakih et al., 2006; Pickering, Lackey, and Crain, 2000; Racault, Langlais, and Naslain, 1994; Racault et al., 1994).

The fabrication of single-phase, bulk, dense samples of Ti3SiC2 proved to be more elusive, however. Attempts to synthesize them in bulk always resulted in samples containing, in most cases, TiC, and sometimes SiC, as ancillary, unwanted phases (Lis et al., 1993; Morgiel, Lis, and Pampuch, 1996; Pampuch and Lis, 1995; Pampuch et al., 1989). Consequently, before our breakthrough in synthesis (Barsoum and El-Raghy, 1996), little was known about Ti3SiC2, and much of what was known has since been shown to be incorrect. For example, despite a sentence buried in one of Nowotny's papers claiming Ti3SiC2 does not melt but dissociates at 1700 °C into TiC and a liquid (Nowotny and Windisch, 1973), the erroneous information that it has a melting point of over 3000 °C is still being disseminated by some.

Furthermore, and before our work, many of the Ti3SiC2 samples fabricated in bulk form were unstable above ≈1450 °C (Pampuch et al., 1989; Racault, Langlais, and Naslain, 1994). It is now established that Ti3SiC2, if pure, is thermally stable to at least 1700 °C in inert atmospheres (Chapter 4). Another important misconception that tempered the enthusiasm for Ti3SiC2 was, again, the erroneous belief that its oxidation resistance above 1200 °C was poor (Okano, Yano, and Iseki, 1993; Racault, Langlais, and Naslain, 1994; Tong et al., 1995).

Despite the aforementioned pitfalls, Pampuch, Lis, and coworkers (Lis et al., 1993; Morgiel, Lis, and Pampuch, 1996; Pampuch, 1999; Pampuch and Lis, 1995; Pampuch et al., 1989) came closest to fabricating pure bulk samples; their best samples were ≈80–90 vol% pure (balance TiC). Nevertheless, using these samples they were the first to show that Ti3SiC2 was elastically quite stiff, with Young's and shear moduli of 326 and 135 GPa, respectively, and yet machinable (Lis et al., 1993). They also confirmed its relative softness (Vickers hardness of 6 GPa) and noted that the high stiffness-to-hardness ratio was more in line with ductile metals than ceramics, and labeled it a “ductile” ceramic. Apart from these properties, and a report that the thermal expansion of Ti3SiC2 was 9.2 × 10−6 K−1 (Iseki, Yano, and Chung, 1990), no other properties were known.

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that reference to Ti3SiC2 in the literature occurs in another context. This phase was sometimes found at Ti/SiC interfaces annealed at high temperatures (Iseki, Yano, and Chung, 1990; Morozumi et al., 1985; Wakelkamp, Loo, and Metselaar, 1991). Ti3SiC2 was also encountered when Ti was used as a braze material to bond SiC to itself, in SiC-Ti-rein...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Structure, Bonding, and Defects

- Chapter 3: Elastic Properties, Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy

- Chapter 4: Thermal Properties

- Chapter 5: Electronic, Optical, and Magnetic Properties

- Chapter 6: Oxidation and Reactivity with Other Gases

- Chapter 7: Chemical Reactivity

- Chapter 8: Dislocations, Kinking Nonlinear Elasticity, and Damping

- Chapter 9: Mechanical Properties: Ambient Temperature

- Chapter 10: Mechanical Properties: High Temperatures

- Chapter 11: Epilogue

- Index