![]()

1 Biochemistry of Fruit Ripening

Sonia Osorio and Alisdair R. Fernie

Introduction

This chapter is intended to provide an overview of the key metabolic and regulatory pathways involved in fruit ripening, and the reader is referred to more detailed discussions of specific topics in subsequent chapters.

The quality of fruit is determined by a wide range of desirable characteristics such as nutritional value, flavor, processing qualities, and shelf life. Fruit is an important source of supplementary diet, providing minerals, vitamins, fibers, and antioxidants. In particular, they are generally rich sources of potassium, folate, vitamins C, E, and K as well as other phytonutrients such as carotenoids (beta-carotene being a provitamin A) and polyphenols such as flavonols (Saltmarsh et al., 2003). A similar, but perhaps more disparate, group of nutrients is associated with vegetables. Thus nutritionists tend to include fruits and vegetables together as a single “food group,” and it is in this manner that their potential nutritional benefits are normally investigated and reported. Over the past few decades, the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables has been linked to a reduction in a range of chronic diseases (Buttriss, 2012). This has led the WHO to issue a recommendation for the consumption of at least 400 g of fruits and vegetables per day. This in turn has prompted many countries to issue their own recommendations regarding the consumption of fruits and vegetables. In Britain this has given rise to the five-a-day recommendation. A portion in the United Kingdom is deemed to be around 80 g; so five-a-day corresponds to about 400 g per day. Other countries have opted for different recommendations (Buttriss, 2012), but all recognize the need for increased consumption.

The rationale for the five-a-day and other recommendations to increase fruit and vegetable consumption comes from the potential link between high intake of fruits and vegetables and low incidence of a range of diseases. There have been many studies carried out over the last few decades. The early studies tended to have a predominance of case-control approaches while recently more cohort studies, which are considered to be more robust, have been carried out. This has given rise to many critical and systematic reviews, examining this cumulative evidence base, over the years which have sometimes drawn disparate conclusions regarding the strength of the links between consumption and disease prevention (Buttriss, 2012). One of the most recent (Boeing et al., 2012) has concluded that there is convincing evidence for a link with hypertension, chronic heart disease, and stroke and probable evidence for a link with cancer in general. However, there might also be probable evidence for an association between specific metabolites and certain cancer states such as between carotenoids and cancers of the mouth and pharynx and beta-carotene and esophageal cancer and lycopene and prostate cancer (WRCF and American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007). There is also a possible link that increased fruit and vegetable consumption may prevent body weight gain. This reduces the propensity to obesity and as such could act as an indirect reduction in type 2 diabetes, although there is no direct link (Boeing et al., 2012). Boeing et al. (2012) also concluded there is possible evidence that increased consumption of fruits and vegetables may be linked to a reduced risk of eye disease, dementia, and osteoporosis. In almost all of these studies, fruits and vegetables are classed together as a single “nutrient group.” It is thus not possible in most cases to assign relative importance to either fruits or vegetables. Similarly, there is very little differentiation between the very wide range of botanical species included under the banner of fruits and vegetables and it is entirely possible that beneficial effects, as related to individual disease states, may derive from metabolites found specifically in individual species.

Several studies have sought to attribute the potential beneficial effects of fruits and vegetables to specific metabolites or groups of metabolites. One such which has received a significant amount of interest is the antioxidants. Fruit is particularly rich in ascorbate or vitamin C which represents one of the major water-soluble antioxidants in our diet and also in carotenoids such as beta-carotene (provitamin A) and lycopene which are fat-soluble antioxidants (Chapter 4). However, intervention studies using vitamin C or indeed any of the other major antioxidants, such as beta-carotene, often fail to elicit similar protective effects, especially in respect of cancer (Stanner et al., 2004). Polyphenols are another group of potential antioxidants that have attracted much attention in the past. The stilbene—resveratrol-–which is found in grapes, for example, has been associated with potential beneficial effects in a number of diseases (Baur and Sinclair, 2006). Similarly, the anthocyanins (Chapter 5), which are common pigments in many fruits, have again been implicated with therapeutic properties (Zafra-Stone et al., 2007). It is possible that these individual molecules may be having quite specific nutrient–gene expression effects. It is difficult to study these effects in vivo, as bioavailability and metabolism both in the gut and postabsorption can be confounding factors.

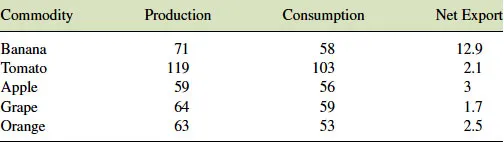

Although there are recommendations across many countries regarding the consumption of fruits and vegetables, in general, the actual intake falls below these recommendations (Buttriss, 2012). However, trends in consumption are on the increase driven potentially by increasing nutritional awareness on the part of the consumer and an increasing diversity of available produce. Fruit is available either fresh or processed in a number of ways the most obvious being in the form of juices or more recently smoothies. The list of fruits and vegetables traded throughout the world is both long and diverse. The FAO lists over 100 “lines” of which 60 are individual fruits or vegetables or related groups of these commodities. The remaining “lines” are juices and processed or prepared material. However, the top five traded products are all fruits and these are banana, tomato, apple, grape, and orange. In 1982–1984 these five between them accounted for around half of global trade in fruits and vegetables; by 2002–2004, this had fallen to around 40% (European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, 2007). This probably reflects a growing trend toward diversification in the fruit market, especially in respect of tropical fruit. These figures represent traded commodities and in no way reflect global production of these commodities. In fact only about 5–10% of global production is actually traded. The EU commissioned a report in 2007 to examine trends in global production, consumption, and export of fruits and vegetables between 1980–1982 and 2002–2004. This demonstrated that fruits and vegetables represented one of the fastest growing areas of growth within the agricultural markets with total global production increasing by around 94% during this period. Global fruit production in 2004 was estimated at 0.5 billion tonnes. The growth in fruit production, at 2.2% per annum, was about half that for vegetables during this period. The report breaks these figures down into data for the most commonly traded commodities and the results for production, consumption, and net export in 2002–2004 are summarized in Table 1.1. Not all of the five major fruit commodities increased equally during this period. Banana and tomato production both doubled; apple and orange production both went up by about 50% while grape stagnated or even declined slightly during this period.

Table 1.1 Global production, consumption, and net export of the five major (million tons) fruit commodities in 2002–2004. Data from European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (2007).

Global consumption of fruits and vegetables rose by 52% between 1992–2004 and 2002–2004 (European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, 2007). This means that global fruit and vegetable consumption rose by around 4.5% per annum during this period. This exceeded the population growth during the same period and as such suggested an increased consumption per capita of the population. Again the results for the consumption amongst the five major traded crops were variable with increases of banana, tomato being higher at 3.9% per annum and 4.5% per annum, respectively, while grapes (1.6% per annum) and oranges (1.9% per annum) were lower.

The net export figures reported above do not include trade between individual EU countries; however, even taking this into account, it is clear that only a small proportion of fruit production enters international trade. A major problem with trade in fresh fruit is the perishable nature of most of the commodities. This requires rapid transport or sophisticated means of reducing or modifying the fruits' metabolism. This can be readily achieved for some fruits, such as apple, by refrigeration; however, several fruits, such as mango, are subject to chilling injury that limits this approach. Other methods that are employed are the application of controlled or modified atmospheres (Jayas and Jeyamkondan, 2002). Generally an increase in carbon dioxide accompanied by a reduction in oxygen, will serve to reduce ethylene synthesis and respiration rate. The application of chemicals such as 1-MCP, an ethylene analog, can also significantly reduce ripening rates (Blankenship and Dole, 2003). Genetically modifying the fruit, for instance to reduce ethylene production, can also lead to an increase in shelf life (Picton et al., 1993).

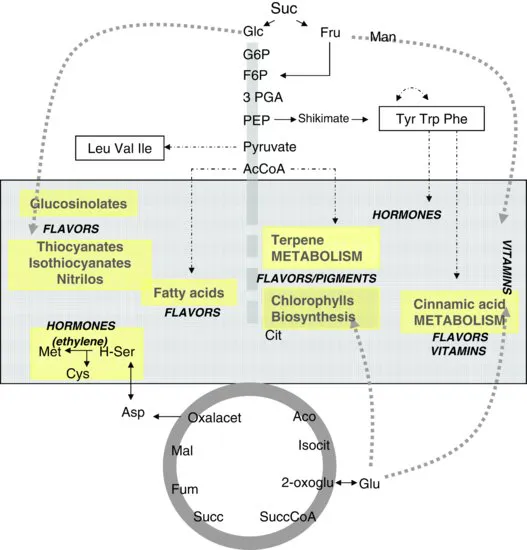

Fruit ripening is highly coordinated, genetically programmed, and an irreversible developmental process involving specific biochemical and physiological attributes that lead to the development of a soft and edible fruit with desirable quality attributes (Giovannoni, 2001). The main changes associated with ripening include color (loss of green color and increase in nonphotosynthetic pigments that vary depending on species and cultivar), firmness (softening by cell-wall-degrading activities), taste (increase in sugar and decline in organic acids), and odor (production of volatile compounds providing the characteristic aroma). While the majority of this chapter will concentrate on central carbon metabolism, it is also intended to document progress in the understanding of metabolic regulation of the secondary metabolites of importance to fruit quality. These include vitamins, volatiles, flavonoids, pigments, and the major hormones. The interrelationship of these compound types is presented in Figure 1.1. Understanding the mechanistic basis of the events that underlie the ripening process will be critical for developing more effective methods for its control.

Central Carbon Metabolism

Sucrose, glucose, and fructose are the most abundant carbohydrates and are widely distributed food components derived from plants. The sweetness of fruits is the central characteristic determining fruit quality and it is determined by the total sugar content and by their ratios among those sugars. Accumulation of sucrose, glucose, and fructose in fruits such as melons, watermelons (Brown and Summers, 1985), strawberries (Fait et al., 2008) and peach (Lo Bianco and Rieger, 2002) is evident during ripening; however, in domesticated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) only a high accumulation of the two hexoses is observed, whereas some wild tomato species (i.e., Solanum chmielewskii) accumulate mostly sucrose (Yelle et al., 1991). The variance in relative levels of sucrose and hexoses is most likely due to the relative activities of the enzymes responsible for the degradation of sucrose, invertase, and sucrose synthase.

The importance of the supply to, and the subsequent mobilization of sucrose in, plant heterotrophic organs has been the subject of intensive research effort over many years (Miller and Chourey, 1992; Zrenner et al., 1996; Wobus and Weber, 1999; Heyer et al., 2004; Roitsch and Gonzalez, 2004; Biemelt and Sonnewald, 2006; Sergeeva et al., 2006; Lytovchenko et al., 2007). While the mechanisms of sucrose loading into the phloem have been intensively studied over a similar time period (Riesmeier et al., 1993; Burkle et al., 1998; Meyer et al., 2004; Sauer et al., 2004), those by which it is unloaded into the sink organ (the developing organs attract nutrients) have only been clarified relatively recently and only for a subset of plants studied (Bret-Harte and Silk, 1994; Viola et al., 2001; Kuhn et al., 2003; Carpaneto et al., 2005). Recently, in the tomato fruit, the path of sucrose unloading in early developmental stages has been ...