- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Covers the significant embedded computing technologies—highlighting their applications in wireless communication and computing power

An embedded system is a computer system designed for specific control functions within a larger system—often with real-time computing constraints. It is embedded as part of a complete device often including hardware and mechanical parts. Presented in three parts, Embedded Systems: Hardware, Design, and Implementation provides readers with an immersive introduction to this rapidly growing segment of the computer industry.

Acknowledging the fact that embedded systems control many of today's most common devices such as smart phones, PC tablets, as well as hardware embedded in cars, TVs, and even refrigerators and heating systems, the book starts with a basic introduction to embedded computing systems. It hones in on system-on-a-chip (SoC), multiprocessor system-on-chip (MPSoC), and network-on-chip (NoC). It then covers on-chip integration of software and custom hardware accelerators, as well as fabric flexibility, custom architectures, and the multiple I/O standards that facilitate PCB integration.

Next, it focuses on the technologies associated with embedded computing systems, going over the basics of field-programmable gate array (FPGA), digital signal processing (DSP) and application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) technology, architectural support for on-chip integration of custom accelerators with processors, and O/S support for these systems.

Finally, it offers full details on architecture, testability, and computer-aided design (CAD) support for embedded systems, soft processors, heterogeneous resources, and on-chip storage before concluding with coverage of software support—in particular, O/S Linux.

Embedded Systems: Hardware, Design, and Implementation is an ideal book for design engineers looking to optimize and reduce the size and cost of embedded system products and increase their reliability and performance.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

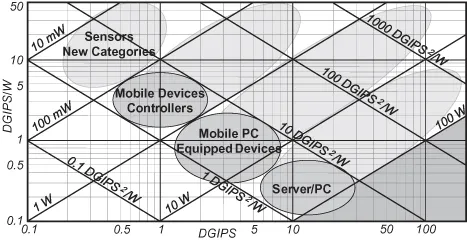

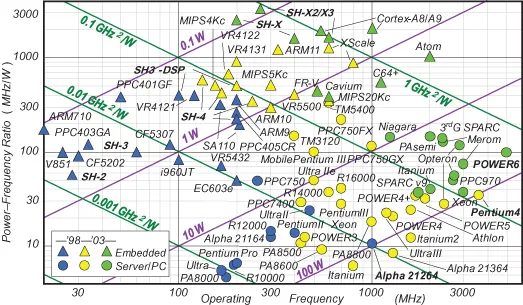

1.1 MULTICORE CHIP WITH HIGHLY EFFICIENT CORES

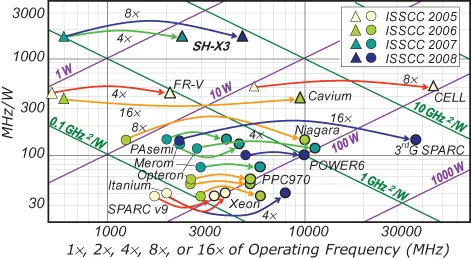

1.2 SUPERH™ RISC ENGINE FAMILY (SH) PROCESSOR CORES

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- 1 Low Power Multicore Processors for Embedded Systems

- 2 Special-Purpose Hardware for Computational Biology

- 3 Embedded GPU Design

- 4 Low-Cost VLSI Architecture for Random Block-Based Access of Pixels in Modern Image Sensors

- 5 Embedded Computing Systems on FPGAs

- 6 FPGA-Based Emulation Support for Design Space Exploration

- 7 FPGA Coprocessing Solution for Real-Time Protein Identification Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- 8 Real-Time Configurable Phase-Coherent Pipelines

- 9 Low Overhead Radiation Hardening Techniques for Embedded Architectures

- 10 Hybrid Partially Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Routing for 3D Networks-on-Chip

- 11 Interoperability in Electronic Systems

- 12 Software Modeling Approaches for Presilicon System Performance Analysis

- 13 Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Implementation in Embedded Systems

- 14 Reconfigurable Architecture for Cryptography over Binary Finite Fields

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app