![]()

1

Why Management Matters

One of the motivations in writing this book was to tackle the following puzzle:

- Do we know how to generate sustainably high performance in companies? Yes we do.

- Do companies consistently follow this established formula? No they don't.

On the face of it, this seems strange. Surely human nature compels us to seek out better ways of doing things? Surely competition between companies creates a survival-of-the-fittest push for constant improvement? Well, yes it does, but there are also many other forces at work that can frustrate our ability to do what we know to be right. Sometimes these forces prevail, leaving everyone stuck with an inferior model.

The established “formula” for delivering high performance is what I call a people-centric approach to management. It involves hiring talented and motivated people, providing them with the competencies they need to succeed, and – most important of all – putting in place a system of management that enables them to do their best work.

Do you buy the argument that a people-centric approach to management is key to long-term success? When I ask this question in seminars, the majority of people say yes: they intuitively buy the argument. However, when I probe further, it becomes clear that a significant number are more sceptical – they aren't convinced its true, but they figure that investing in people doesn't do much harm and perhaps it is just one of the costs of being in business, so they go along with it. Then there are the cynics, usually a fairly small number of people, who strongly disagree – they think this emphasis on people is misguided or insincere, or perhaps even a Machiavellian way for managers to further their own objectives.

I will get back to the views of the cynics later, in Chapter 3, but for now, I want to concentrate on those in the first two groups. I was in the first category when I started researching this book. I saw the link between investing in people and corporate performance as axiomatic – self-evidently true, but so fundamental that it probably couldn't be proved.

Drivers of Corporate Performance

It turns out I was half-right. When you collect the evidence together, it shows that the axiom is not only correct but is also objectively verifiable. Several recent academic studies have shown that companies with engaged and happy employees outperform those that do not1. There has also been a lot of applied research in recent years, such as the “Engage for Success” movement in the UK, which has drawn similar conclusions2.

One particular study is worth recounting here in detail. A London Business School Professor, Alex Edmans, studied the “Best Companies to Work For” in the United States and focused on their stock market performance over a 25 year period. He showed that “A value-weighted portfolio of the 100 Best Companies earned an annual alpha of 3.5% from 1984 to 2009.” In plain English, this means that if you invested your own pension in these companies, and left it there, you would get a significantly better return – 3.5% per year – than the average fund manager3. Edmans showed, in other words, that not only do these “Best Companies to Work For” have better performance over the long-term than those in the market as a whole but also the stock market fails to pick up on their superior prospects.

Remember, stock markets are supposed to be efficient. If Apple announces a new category-busting product or if Roche gets a patent on a new cancer drug, their shares rise in anticipation of future growth. However, when Fortune magazine announces the annual list of winners in the Best Companies to Work For ranking, the stock market doesn't care. This information just doesn't make it on to the analysts’ radar screens. Implicitly, investors seem to be saying, “OK, so you take care of your employees well, good for you; but we won't be buying up your shares until we have seen how that investment works its way through to the bottom line.”

To say this even more simply, analysts and professional investors don't buy this “soft stuff.” Even with solid evidence that investing in people makes a long-term difference to performance, they retain their sceptical position. As one analyst said, “Costco's management is focused on … employees to the detriment of shareholders. To me, why would I want to buy a stock like that?4”

So why the scepticism? To answer this question, it is useful to go back to economic theory because stock markets are heavily influenced by that body of thinking. For many economists, employees are still nothing more than an input cost. Companies invest in workers in the same way they invest in plant and machinery and technology; they spend as little as they can, they sell their product for as much as they can, and the difference is profit. If this is true, then spending more than you have to on employees is just throwing money away. Of course, this is a gross simplification, and indeed there are many alternative economic theories that recognize the unusual nature of human capital, but old theories die hard, and the aggregate view is still one that treats “intangible assets” like expertise and discretionary effort with suspicion.

Perhaps this is starting to change. An extensive research program led by Professors John van Reenen (London School of Economics) and Nick Bloom (Stanford) over the last decade has sought to shed light on why we see big productivity differences between seemingly similar companies. They show that quality of management is the key – some companies simply use better management practices, in a more consistent way, than others and these practices have a significant impact on productivity and performance. This isn't a surprising finding to those who work in or study the field of management, but it is helping to shape the conversation among economists about how companies really work.

Regardless of what investors and analysts think, the key point is that there is a well-established formula for achieving long-term corporate success, and it is about investing in people and fostering a high level of employee engagement. To be clear, these effects are true in aggregate, but not in every specific case, and there are many other drivers of corporate success as well. But these are small caveats; the overall body of evidence is still sufficiently strong to make investing in people a smart strategy for your company, and investing in people-centric companies a smart strategy for your pension.

Quality of Life Considerations

So much for the investor or owner's perspective. What about the broader view? How does a people-centric approach to business affect society as a whole? The evidence here is equally persuasive. There have been many research studies showing, for example, that engaged employees have lower levels of absenteeism, high levels of overall well-being, and even lower incidences of disease5. Moreover, the principle of employee well-being is as old as the field of management itself. Students of business history are familiar with the concept of Corporate Welfarism from the 1880s6 and the Quality of Work Life movement in the 1950s.

Today, there is currently a huge amount of interest in happiness and positive psychology. Studies have ranked countries by how happy their people are (top of the list: Denmark)7. Policy-makers have put programs in place to foster more positive attitudes at work and home. In the UK, Prime Minister David Cameron has picked up on this trend, by launching an initiative to start measuring National Well-being alongside traditional economic measures such as GDP. He said we need to “start measuring our progress as a country not just by how our economy is growing, but by how our lives are improving; not just by our standard of living, but by our quality of life.8” (for more information on this initiative, see the website www.engageforsuccess.org).

Of course there are many factors that shape our quality of life and the world of work only represents one part of the story. But for those of us in full-time employment, the quality of our working lives has a huge impact on our overall well-being and indirectly on the well-being of our families. Think of it from the employer's perspective. If your employees spend 40–50 hours a week in the office, you owe it to them to make it as worthwhile and pleasant as possible – not just because that is morally the right thing to do but also because happy employees are healthier and more productive.

Again, the evidence suggests that a people-centric model in the corporate world isn't just good for performance; it is also good for the people working in that company and society as a whole. Now, I realize that this sort of “win-win” story makes people a bit suspicious: surely there is a catch? Surely there is, at least, an opportunity cost to this sort of investment?

Well, there might be, but the truth is, we don't know. The reason we don't know is that despite all the evidence that this people-centric approach is better, there are actually remarkably few companies that have implemented it on a consistent basis.

The Rhetoric–Reality Gap

Greg Smith caused quite a stir in March 2012 when he wrote a scathing op-ed in The New York Times, “Why I am leaving Goldman Sachs.9” He said the company was morally bankrupt and that its culture of teamwork, integrity, and humility had been lost.

I don't have the inside story on what Goldman is really like, but Greg Smith's description sounds remarkably like every other investment bank on Wall Street or in the City of London. It is the oldest story in the book: when big bonuses are on the line, people become greedy, they look out for their own interests, and collaboration, integrity, and humility go out the window. The culture in these banks is individualistic and aggressive. Bad management is tolerated. People are expendable.

Whether accurate or not, my point here is a simple one, namely that the world Greg Smith described in his New York Times article was exactly the opposite of what Goldman Sachs says about itself. The company website says, “Our people are our greatest asset. We say it often and with good reason … at every step of our employees’ careers we invest in them… our goal is to maximize individual potential.”

So if we want to get a fix on how people-centric companies really are, we can start by entirely disregarding any public statements they might make. A much better approach is to ask employees, preferably in an anonymous way, about how happy or engaged they are, or how good their managers are. It is also useful to gather objective data about, for example, levels of employee turnover or cases of harassment and bullying. Once you get this sort of information, the story that emerges is not a happy one. Here are some examples of recent studies:

- Human resource consultancy Towers Perrin (now Towers Watson) measures employee engagement levels across countries and sectors. On an aggregate level, its 2003 data showed that 17% of the sample were highly engaged, 64% were moderately engaged, and 19% were disengaged with their work.

- A poll of workers in the UK commissioned by the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) in 2008 found that only 43% of employees were fully engaged in the work they were doing10.

- The UK's Chartered Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD) does a quarterly “employee outlook” survey. In July 2012, they found that only 38% of employees were actively engaged at work, with 59% neutral, and 3% disengaged. While respondents felt their managers mostly treated them fairly (71%), less than half were satisfied with the level of coaching and feedback they received11.

The picture that emerges from these and other studies is pretty clear. There are some very well-managed companies out there with highly motivated and engaged employees. There are also some dire companies with miserable employees who are investing more time looking for a new job than doing the work they are paid for. The vast majority of companies are stuck in the middle, no doubt trying hard to improve their people-management practices but without the buy-in they need to make it a real priority and without the results to show for it. Such companies typically have pockets of excellence, but a great deal of mediocrity as well.

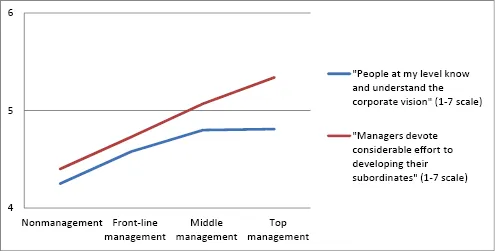

There is, in short, a rhetoric–reality gap between the words and policies of top executives and the experiences of front-line employees. Figure 1.1 provides an illustration of this gap, from some research I was involved with12: it shows employees answer the same questions less positively the lower you go in the corporate hierarchy.

This gap causes problems in a couple of ways. First, it creates confusion: when employees see a disconnect between the stated priorities of the company and the decisions ...