eBook - ePub

Polysaccharide-Based Nanocrystals

Chemistry and Applications

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Polysaccharide-Based Nanocrystals

Chemistry and Applications

About this book

Polysaccharide nanocrystals, an emerging green nanoingredient (nanomaterial) with high crystallinity obtained by acid hydrolysis of biomass-based polysaccharides, are of scientific and economic significance owing to their abundance, biodegradation potential, and fascinating functional performance. This versatile class of materials can be used in nanocomposites such as rubber or polyester, and in functional materials such as drug carriers, bio-inspired mechanically adaptive materials or membranes, to name but a few.

This book encompasses the extraction, structure, properties, surface modification, theory, and mechanism of diverse functional systems derived from polysaccharide nanocrystals.

This highly sought-after trendy book is currently the only monograph devoted to the most current knowledge pertaining to this exciting subject area. It is ideal for researchers and stakeholders who wish to broaden and deepen their knowledge in the fast-moving and rapidly expanding R&D field of polymeric materials.

This book encompasses the extraction, structure, properties, surface modification, theory, and mechanism of diverse functional systems derived from polysaccharide nanocrystals.

This highly sought-after trendy book is currently the only monograph devoted to the most current knowledge pertaining to this exciting subject area. It is ideal for researchers and stakeholders who wish to broaden and deepen their knowledge in the fast-moving and rapidly expanding R&D field of polymeric materials.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Polysaccharide-Based Nanocrystals by Jin Huang,Peter R. Chang,Ning Lin,Alain Dufresne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Polysaccharide Nanocrystals: Current Status and Prospects in Material Science

Jin Huang, Peter R. Chang, and Alain Dufresne

1.1 Introduction to Polysaccharide Nanocrystals

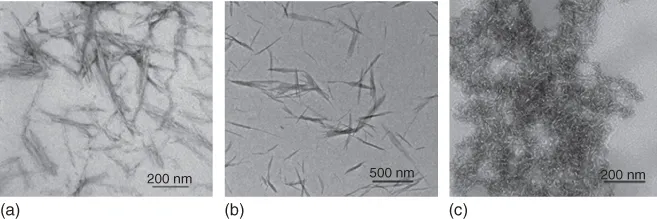

Native polysaccharides usually consist of crystalline and amorphous regions; to produce highly crystalline polysaccharide nanocrystals (PNs) the amorphous component is removed through acid hydrolysis. The morphologies and dimensions of PNs strongly depend on the different sources of biomass and different extraction methods. Figure 1.1 depicts the transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of rod-like cellulose and chitin nanocrystals, and platelet-like starch nanocrystals [1]. It is worth noting that the surface properties of PNs are influenced by the extraction methods. The H2SO4 hydrolysis protocol usually produces sulfate groups on the surface of PNs, resulting in improved dispersibility in water and lower thermal stability [2, 3]. By comparison, PNs with higher thermal stability may result from HCl hydrolysis, but the resultant suspension aggregates easily in water and shows poor dispersibility [4, 5]. Moreover, PNs with improved dispersibility in water and thermal stability can also be successfully obtained using an acid mixture consisting of hydrochloric acid and an organic acid, such as acetic or butyric acid [6]. In exploring economical routes for enhancing the efficiency and yield of PN production many approaches have been attempted including pretreatments [7], hydrothermal methods [5], microwave- and ultrasonic-assisted technologies [8, 9], and so on.

Figure 1.1 TEM images of cellulose nanocrystals from cotton linter with 200–300 nm length and 10–15 nm width (a); chitin nanocrystals from crab shell with 200–600 nm length and 10–20 nm width (b); and pea starch nanocrystals 6–8 nm thick, 40–60 nm in length, and 15–30 nm in width (c).

The rod-like nanocrystals of cellulose and chitin show a predominant characteristic of high aspect ratios, and thus their suspensions display many unique properties, such as cholesteric liquid crystallinity and flow birefringence. These properties showed a dependence on concentration, and phase behavior was affected by electrolytes [10–14]. When the suspensions reached a critical concentration, the rod-like nanocrystals exhibited an ordered phase displaying flow birefringence and nematic or chiral nematic structures. Cellulose nanocrystals (CNs) exhibit birefringence not only in aqueous suspensions but also in organic solvents such as dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), dimethyl formamide (DMF), cyclohexane, and toluene [15, 16]. At the same time, it has been found that surface-modified CNs, that is, carboxymethylated, tetramethyl-piperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO) oxidized [17], or silylated CNs, displayed birefringence in suspension with tetrahydrofuran (THF) [18]. CN suspensions possess distinctive rheological properties [19] and may form gels from aqueous glycerol suspensions with careful evaporation at 70 °C, when the CN concentration is below 3 wt% [20]. Starch nanocrystals have a unique platelet-like structure and often tend to aggregate in aqueous solution [21], although a stable suspension can be achieved by adjusting the pH [22]. Detailed descriptions of the structure and properties of PNs can be found in Chapter 2.

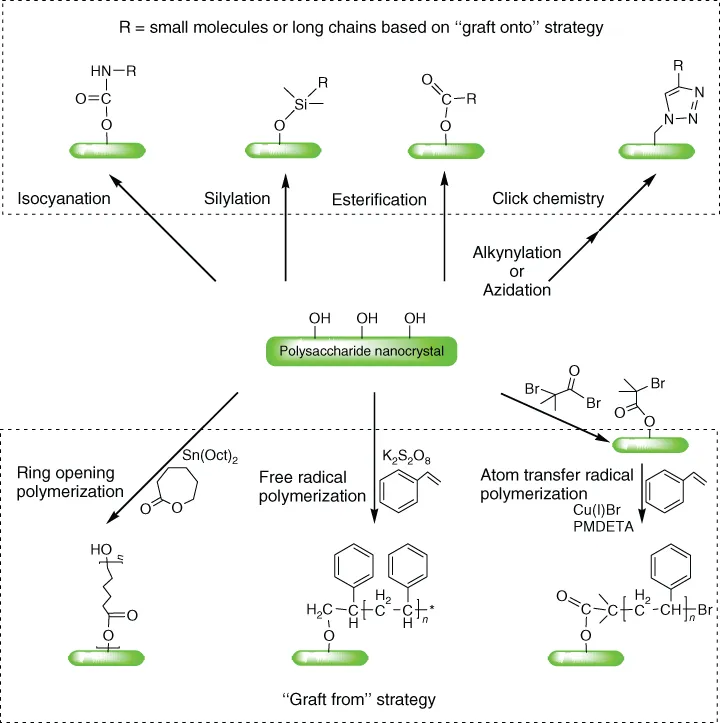

The abundant hydroxyl groups on the surface of PNs contribute to their positive surface chemical properties and are therefore an essential route to altering surface structure, regulating surface properties, and developing functional materials. The common methodologies for chemical modification of PNs, presented in Figure 1.2, can be classified in three categories: small molecule conjugation, “graft onto,” and “graft from” strategies for polymers. There are three main mechanisms of small molecule conjugation, including isocyanation [23], silylation [18, 24], and esterification [25], depending on the availability and activity of the surface hydroxyl groups. In addition, alkynylation and azidation can be used to import alkynyl or azide groups for click chemistry using the Huisgen reaction [26]. The “graft onto” strategy for polymer grafting abides by the mechanism for small molecule conjugation, but the grafting efficiency may be inhibited by the steric hindrance of large polymer chains in contrast with the conjugation efficiency of small molecules [27–29]. In addition, hydroxyl groups on the surface of PNs can directly initiate ring opening polymerization (ROP) of lactones [30] and free radical polymerization (FRP) of olefins to graft polymer chains based on the “graft from” strategy [31]. At the same time, by using small molecule conjugation to import initiating groups, controlled radical polymerization, that is, atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), can be achieved using the functionalized Br atom as the initiating point [32]. Detailed surface chemical modification of PNs is described in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.2 Chemical modification methodology and typical examples toward the surface of polysaccharide nanocrystals.

1.2 Current Application of Polysaccharide Nanocrystals in Material Science

PNs have been widely used as a reinforcing biomass-based filler to modify polymeric materials with matrixes of rubber, polyolefin, polyurethane and waterborne polyurethane, polyester, and natural polymer plastics of starch and protein. The reinforcing mechanism depends mainly on the formation of a three-dimensional PN network and the interfacial miscibility between the PN surface and matrix. The former abides by the percolation model and requires PN content to be higher than a critical concentration; the latter can be improved by the formation of strong interfacial interaction or by a co-continuous phase mediated by surface-grafted polymer chains that alter the surface chemical structure through surface modification of PNs [33–37]. Casting/evaporation processing is the most suitable method for development of the three-dimensional PN network because it provides enough freedom to form hydrogen bonds among PNs before and during solidification of the nanocomposite [37–41]; however, it requires high dispersibility of PNs in the aqueous or organic blending medium during compounding and solvent evaporation. Conversely, melt-compounding and thermoforming methods, such as intensive blending, extrusion, compression molding, and injection molding, may inhibit hydrogen bonding because of the relatively high melting viscosity, and may cleave associations between PNs by shear force and hence fail to construct a three-dimensional network. Furthermore, the commonly used method that uses sulfuric acid hydrolysis for extraction of cellulose and starch nanocrystals results in low thermal stability, which does not match the requirements of thermoprocessing. It is fortunate that physical and chemical modification of the PN surface can significantly enhance thermal stability to contribute to the application of industrial-scale production of PN-modified nanocomposites by thermoprocessing. As mentioned previously, surface physical and chemical modification of PNs play key roles in improving dispersibility in solvent, regulating miscibility with the polymer matrix [37], and enhancing thermal stability to f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Polysaccharide Nanocrystals: Current Status and Prospects in Material Science

- Chapter 2: Structure and Properties of Polysaccharide Nanocrystals

- Chapter 3: Surface Modification of Polysaccharide Nanocrystals

- Chapter 4: Preparation of Polysaccharide Nanocrystal-Based Nanocomposites

- Chapter 5: Polysaccharide Nanocrystal-Reinforced Nanocomposites

- Chapter 6: Polysaccharide Nanocrystals-Based Materials for Advanced Applications

- Chapter 7: Characterization of Polysaccharide Nanocrystal-Based Materials

- Index

- EULA