- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Drying in the Process Industry

About this book

A comprehensive approach to selecting and understanding drying equipment for chemical and mechanical engineers

A detailed reference of interest for engineers and energy specialists working in the process industry field, Drying in the Process Industry investigates the current state of the art of today's industrial drying practices, examines the factors influencing drying's high costs in both equipment and energy consumption, and summarizes key elements for keeping drying operations under budget and performing at peak capacity safely while respecting the environment. Extensive coverage of dryer basics as well as essential procedures concerning the selection of industrial dryers—such as how to gather results of relevant laboratory measurements, carry out small-scale tests, and correctly size equipment—help to inform readers on criteria for generating scalable specifications that greatly assist buying decisions.

Drying in the Process Industry:

- Takes a practical approach to drying equipment, from an author with four decades in the industry

- Describes a diverse array of drying equipment (convective, like flash, spray, fluid-bed, and rotary; contact, like paddle and steam; radiation) from an engineer's perspective

- Provides quick and ready access to drying technologies with references to more detailed literature

- Treats drying in the context of the entire production process

True of all process facilities where drying plays an important role, such as those in the chemical, pharmaceutical, plastics, and food industries, the purchase of improper industrial drying equipment can significantly affect a manufacturer's economic bottom line. With the guidance offered in this book, engineers will be able to confidently choose industrial drying equipment that increases profits, runs efficiently, and optimally suits their needs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

- The energy consumption of drying is 8% of the industrial energy consumption. The industrial energy consumption comprises both processes and buildings.

- The annual water evaporation amounts to 2·1010 kg. This is equivalent to 100-m water columns on 27.2 soccer fields (70·105 m2). As the U.S. economy is about 5.5 times larger than the UK economy, the annual water evaporation in the United States due to drying could be 1.1·1011 kg.

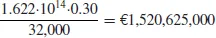

- In 1981, drying required 1.622·1014 kJ. This figure was possibly 10 to 20% lower in 1991.

- (1.622 · 1014)/(2 · 1010) = 8110 kJ per kilogram of evaporated water. This consumption figure includes electricity. Excluding electricity, the consumption figure is possibly 7000 kJ·kg−1. Compared to the heat of evaporation of water at 0°C and atmospheric pressure (i.e., 2500 kJ·kg−1), the consumption figure is quite high. In the chapters to come, the background of this state of affairs is discussed.

- Annual costs are determined by taking 32,000 kJ·nm−3 as the lower heating value of natural gas. The lower heating value is relevant if the heat of condensation of the water vapor in the combustion gases is not recovered. In the UK, an industrial price of €0.30 is typical:

- Flash dryer

- Spray dryer

- Cylinder dryer for paper

- Convective rotary dryer

- Contact rotary dryer

- Fluid-bed dryer

- Different products have very different drying times.

- The product quality often requires a certain dryer type or mode.

- It is often necessary to transport particulate material through a dryer.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Drying as Part of the Overall Process

- Chapter 3: Procedures for Choosing a Dryer

- Chapter 4: Convective Drying

- Chapter 5: Continuous Fluid-Bed Drying

- Chapter 6: Continuous Direct-Heat Rotary Drying

- Chapter 7: Flash Drying

- Chapter 8: Spray Drying

- Chapter 9: Miscellaneous Continuous Convective Dryers and Convective Batch Dryers

- Chapter 10: Atmospheric Contact Dryers

- Chapter 11: Vacuum Drying

- Chapter 12: Steam Drying

- Chapter 13: Radiation Drying

- Chapter 14: Product Quality and Safeguarding Drying

- Chapter 15: Continuous Moisture-Measurement Methods, Dryer Process Control, and Energy Recovery

- Chapter 16: Gas–Solid Separation Methods

- Chapter 17: Dryer Feeding Equipment

- Notation

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app