Music Navigation with Symbols and Layers

Toward Content Browsing with IEEE 1599 XML Encoding

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Music Navigation with Symbols and Layers

Toward Content Browsing with IEEE 1599 XML Encoding

About this book

Music is much more than listening to audio encoded in some unreadable binary format. It is, instead, an adventure similar to reading a book and entering its world, complete with a story, plot, sound, images, texts, and plenty of related data with, for instance, historical, scientific, literary, and musicological contents. Navigation of this world, such as that of an opera, a jazz suite and jam session, a symphony, a piece from non-Western culture, is possible thanks to the specifications of new standard IEEE 1599, IEEE Recommended Practice for Defining a Commonly Acceptable Musical Application Using XML, which uses symbols in language XML and music layers to express all its multimedia characteristics. Because of its encompassing features, this standard allows the use of existing audio and video standards, as well as recuperation of material in some old format, the events of which are managed by a single XML file, which is human and machine readable - musical symbols have been read by humans for at least forty centuries.

Anyone wanting to realize a computer application using IEEE 1599 -- music and computer science departments, computer generated music research laboratories (e.g. CCRMA at Stanford, CNMAT at Berkeley, and IRCAM in Paris), music library conservationists, music industry frontrunners (Apple, TDK, Yamaha, Sony), etc. -- will need this first book-lengthexplanation of the newstandard as a reference.

The book will include a manual teaching how to encode music with IEEE 1599 as an appendix, plus a CD-R with a video demonstrating the applications described in the text and actual sample applications that the user can load onto his or her PC and experiment with.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1.1 Introduction

Important Features of IEEE 1599

Examples of Applications of IEEE 1599 to Increase Music Enjoyment

- An opera. A DVD of an opera allows the user to see the play on the screen, to hear the music, to see the score (including manuscripts), to read the libretto, and to choose alternative renditions (see item 5 below).

- Pieces by a jazz band. The harmonic grid is displayed and the name of the soloist pops up at the beginning of each solo—with didactical tools as presented in jazz textbooks [Baggi 2001] (see item 2 below).

- Music with a “program” or story. For example, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons come with poems by the composer that refer to segments of the music (see item 8 below).

- Music with no apparent meaning. For instance, free jazz of the 1960s–70s is perceived by many as a random collection of meaningless sounds, while an associated video, generated anew each time, may help the listener understand what is meant (see item 2 below).

- A fugue. The theme is highlighted as it gets passed among the different voices.

- A piece of Indian classical music. The scale of the raga is shown and the melodic development is highlighted.

- A piece of several drums, for example, as in African drumming, shows how the rhythmic pulse come from the fact that the hits do not fall together.

- Preservation of the music heritage from the past. To store documents in any media [Haus].

- Musicological study. Ease of queries, for example, all pieces utilizing the lowest note of a grand piano, and questions as to why a certain note is used in a given harmonic context.

- Books about the making of a masterpiece, for example, Kind of Blue, by Miles Davis and John Coltrane [Kahn].

Table of contents

- Cover

- IEEE

- Title page

- Copyright page

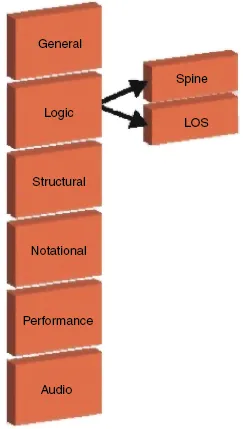

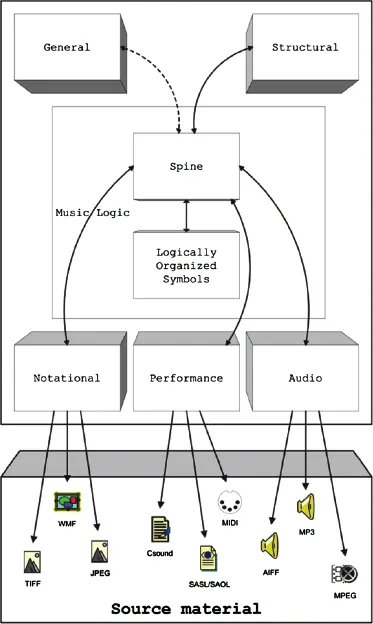

- Illustration of IEEE 1599

- Preface

- A Brief Introduction to the IEEE 1599 Standard

- Contributors

- 1: The IEEE 1599 Standard

- 2: Encoding Music Information

- 3: Structuring Music Information

- 4: Modeling and Searching Music Collections

- 5: Feature Extraction and Synchronization among Layers

- 6: IEEE 1599 and Sound Synthesis

- 7: IEEE 1599 Applications for Entertainment and Education

- 8: Past Projects Using Symbols for Music

- Appendix A. Brief History of IEEE 1599 Standard, and Acknowledgments

- Appendix B. IEEE Document-Type Definitions (DTDs)

- Appendix C. IEEE 1599 Demonstration Videos

- Index