![]()

1

A brief introduction to oral diseases: caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer

Hardy Limeback, Jim Yuan Lai, Grace Bradley, and Colin Robinson

Introduction

By the late 1990s, treating dental disorders cost more than it did to treat mental disorders, digestive disorders, respiratory diseases, and cancer, at least in Canada (Leake 2006). The only group of disorders that exceeded dental treatment in terms of direct cost of illness was cardiovascular disorders (Leake 2006). In dealing with disease, “prevention is better than a cure.” Dental disorders are an enormous burden to society, especially when one now considers the connection between poor oral health and systemic illness, which is a topic that is becoming increasingly important and a focus of other scholarly books. Papananou and Behle (2009) describe the mechanisms linking periodontitis to systemic disease. Dentistry in the past has been treatment oriented, but we are witnessing an unprecedented interest in prevention. It is obviously better to prevent the disease in the first place, than treat it once it has taken hold. This is quite true for most diseases in medicine.

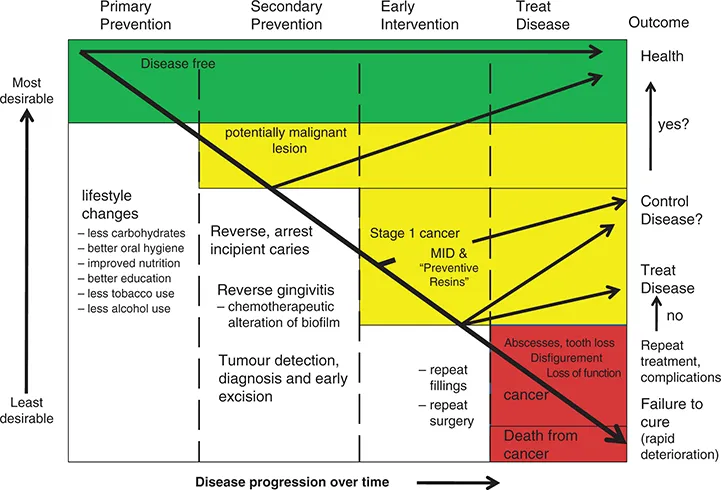

The three general disease categories of focus in dentistry are dental decay, periodontal disease, and oral cancer. In the case of oral cancer, associated with a high degree of mortality, preventive dentistry even saves lives. Figure 1-1 summarizes the general hierarchy of prevention in dentistry.

The goals of preventive dentistry are to avoid disease altogether. Maintaining a disease-free state (green) can result from primary prevention. When lifestyle changes are made early on, the risk for developing dental disease are minimized. Secondary prevention and early intervention (yellow) can be used to reverse the initiation of disease. An outcome of good health can still be achieved when incipient enamel lesions are reversed before cavities form, when gingivitis is reversed before periodontitis sets in, when dysplasia is found and excised before cancer develops, thus returning to good health and controlling dental disease is possible. Far too often though, dentists spend most of their time treating dental disease in an endless cycle of repeat restorations and surgery (red), which leads to tooth loss, and in the case of cancer, disfigurement and even death.

No one would disagree that it would be better to maintain oral health throughout life, never to have had any kind of dental disease. This is the goal of primary prevention (green area in Figure 1-1). Throughout the book we have used a ‘traffic light’ color system: “green is good,” “yellow means caution,” and red means “stop! fix the problem.” A similar theme has been used commercially in buffering capacity tests and in risk assessment (Ngo and Gaffney 2005).

Primary prevention for dental diseases such as dental caries and periodontal disease could include eating a healthy diet, maintaining low intake of fermentable carbohydrates, practicing meticulous oral hygiene throughout life, and reducing the other risk factors, such as smoking, that would normally lead to dental disease. In the case of oral cancer, primary prevention might include successful smoking cessation counseling, where a patient has been smoking for quite some time. Obviously it would be better for the patient not to have smoked at all.

Secondary prevention (‘caution’) suggests that the disease has started but can be reversed, and good health can still be achieved. For example, incipient carious lesions (white spot enamel lesions) can be arrested and reversed using appropriate ‘preventive’ measures so that a full-blown carious lesion never develops. It was well established that frequent oral hygiene reinforcement by dental professionals can prevent caries, gingivitis, and periodontal disease (Axelsson and Lindhe 1978).

Secondary periodontal disease prevention might include other strategies such as the chemical elimination of bacteria known to initiate periodontal disease. Secondary prevention of oral cancer could include identification of dysplastic tissue and its removal as well as stopping the irritation that leads to the dysplasia.

It will be obvious to the reader that this book has attempted to be all-inclusive: a comprehensive text on prevention of oral diseases. Despite this ambitious goal, there is a heavy concentration and discussion around dental decay. It is important to realize that the literature on prevention of caries is quite extensive, compared to the prevention of periodontitis or oral cancer. If the reader is interested in the treatment of periodontal disease and oral cancer, it is suggested that the reader turn to more comprehensive reading material on the management of these diseases once they have developed. For example, two resources that are excellent reading material are books by Dibart and Ditrich (2009) and Tobia and Hochhauser (2010). Nevertheless, at least some approaches that have been successful in preventing periodontal disease and oral cancers are reviewed in this text.

The global burden of oral diseases

The World Health Organization’s definition of health is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization 1946). One of the true indicators of a good quality of life, of true physical, mental, and social well-being, includes being in good general health. Oral health is an integral part of good general health. Unfortunately, it is the poor and socially disadvantaged that carry most of the burden of poor oral health (Karim et al. 2008). Table 1-1 summarizes some of the general overall risk factors known to be associated with oral diseases, the diseases that result, and their consequences.

People in poverty in developing counties face an overwhelming burden of chronic and severe caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, oral cancer, and other oral disorders. These have detrimental effects on health and create negative behavioral situations that simply contribute more to the cycle of social deprivation. Perhaps only by improving the socio-economic status, education and literacy, oral education, and access to affordable dental care can the cycle of poor oral health be broken.

In most developing countries there are relatively few organized public health programs. If they exist, there is an uneven distribution of these dental services (concentration of dentists in urban centers) and a lack of modern dental services. Clearly, as poor nations begin to improve their standard of living, they will be able to afford to spend money on dental disease prevention.

Table 1-1 Risk factors associated with oral diseases and their consequences

|

| - Rampant dental decay

- Periodontal disease

| - Pain and tooth loss

- Compromised chewing with further nutritional deficiencies

- Social isolation

|

- Poor oral hygiene

- Lack of dental care

| - Dental caries

- Periodontal disease

| - Pain and tooth loss

- Compromised chewing with further nutritional deficiencies

- Social isolation

|

- Poor quality drinking water

| - Disturbed tooth development (e.g., fluorosis)

| - Mottled teeth

- Social isolation

|

- Tobacco products and alcohol in excess

| - Caries in children

- Periodontal disease

- Oral cancer

| - Pain and tooth loss

- Disfigurement

- Death

|

| - Dental caries

- Periodontal disease

| - Pain and tooth loss

- Continued social isolation, poverty

|

- Lack of access to dental care

| | |

- Serious systemic illnesses (e.g., HIV AIDS)

| - Oral infections

- Oral cancer

| |

Dental decay (dental caries): global patterns

Most countries have seen a dramatic decline in oral diseases and are entering the new millennium with less oral disease to manage than in the previous century. Figure 1-2 shows how the prevalence of caries has changed over the decades. In nearly every developed country, there has been a steady decline in dental decay. It is interesting to note, however, that there was a period of extreme shortage of sugar during World War II resulting in an almost elimination of caries. As the supply of sugar returned, so did the caries. This observation was made not only in Japan but also Norway. The decline of caries started many years before the introduction of fluoride and may be related to numerous other factors, such as the introduction of penicillin, the increased use of sugar substitutes, and improved nutrition (which includes better access to calcium and Vitamin D). Experts believe, however, that it was primarily the introduction of fluoride therapies after the 1960s that had a huge impact on dental decay rates (Bratthall et al. 1996).

The reason for the decline in caries worldwide in most developed countries is multifactorial. Other factors may have had an influence on the caries rates. Sucrose has traditionally been used to make preserves of fruit when in season. The introduction of the electric refrigerator likely increased the consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables as well as fresh milk. Penicillin and Vitamin D-fortified milk were introduced during World War II (WWII). Both could have affected caries—penicillin, because it is effectiv...