![]()

Chapter 1

Mathematical Examination of Dielectrics

1.1. Introduction to dielectrics

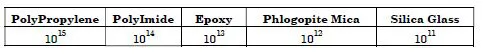

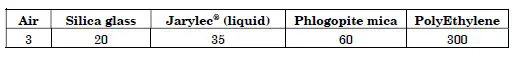

The ideal insulator is a substance with infinite resistivity. In the real world, insulators have resistivity values which are very high, but finite. Table 1.1 gives an indication of the resistivity of a number of insulators, expressed using the MKSA (Meter, Kilogram, Second, Ampere) system.

Table 1.1. Resistivity of a number of dehydrated insulators expressed in [Ω.m] at 20°C

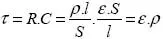

For many applications, the value which best characterizes a material’s insulating capacity is its relaxation time – the time constant of a condenser of any form using that material. This time is given by the following equation [1.1]:

where ε is the permittivity and ρ the resistivity.

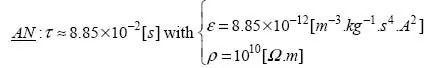

If we take the value of ε to be that in a vacuum – ε0 – we can see that for ρ = 1010 [Ω.m], the relaxation time of charges through the insulator is close to a fraction of [s]; hence, this is not a good insulator. The accepted materials in electrotechnics have relaxation times ranging from around a [s] to several [min] or more; in exceptional conditions, we have even seen relaxation times of around a [year].

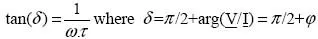

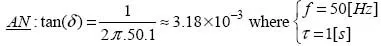

The relaxation time is directly involved in the value of the electrical loss angle δ with alternating current (AC). Indeed, if conduction is the only cause of loss, and if the time constant τ is around a second, the loss angle will be too great for long-term operation at industrial frequencies without the risk of accident [1.2]:

Whilst solid insulators, both organic and mineral-based, can easily deliver sufficiently high relaxation times, liquids are usually far too conductive to be usable. Only a very few aromatic hydrocarbons, including the infamous PolyChloroBiphenyl (PCB or pyralene) or the Mono-Dibenzyl-Toluene (used by Jarylec in Isère) have taken their place in industry, alongside mineral-based oils; other liquids, such as a1cohol, acetone and nitrobenzene, rarely reach values above 104 or l05 [Ω.m] due to their sensitivity to the slightest electrolytic contamination.

Alongside resistivity per se, which depends on conduction in the volume, in practice we often find surface resistivity, which characterizes surface conduction. Many insulators which have very high volume resistivity actually conduct current quite easily along their surface. The most common example is that of a sheet of glass, covered with a layer of water condensation, and therefore no more insulating than wood when not hot-air dried. Other substances, such as paraffin and ebonite, do not present this problem. Yet it is meaningless to express this surface resistivity in numerical terms without drawing the connection between it and external causes such as humidity, temperature, etc. The surface resistance Rs of an “insulator” is expressed in [Ωm], and is calculated by using equation [1.3].

where R is the measured resistance between two electrodes (placed at the surface of the insulator) of length l (transversal to the field) and separated by a distance l' (longitudinal to the field). The measured resistance R therefore relates to a rectangular “insulating” surface with long side l and short side l', and the surface resistance Rs is measured in a square “insulating” surface.

1.1.1. Polarization

Like any material, a dielectric material contains the “two electricities” in equal and considerable quantities, but unlike with conductors, these electricities cannot circulate within the materials under the influence of the field.

If we look at a molecule of dielectric, it contains positive and negative charges. These charges are not free: they are connected by an elastic force which is something like a spring. If we subject the molecule to an electrical field, the charges cannot move about within the insulator under its influence; the positive charge pulls on the spring in the direction of the field, the negative charge pulls in the opposite direction, and the result is that the spring becomes tenser and the two charges move apart from one another slightly. This separation is practically proportional to the field. Under its influence, the molecule is therefore transformed into a system with two equal positive and negative charges, a small distance apart. This is what is known as a doublet or dipole, and the appearance of dipoles constitutes the polarization of the dielectric. If the field is removed, the springs bring the charges back into contact and the polarization disappears (we shall see in Chapter 2 that there are other mechanisms which lead to macroscopic polarization of the material).

1.1.2. Ionization

When we pull too hard on a spring, it will eventually break. Thus, we may imagine that with a critical value of the electrical field, the charges that the springs were holding would suddenly become free, with the insulator becoming a good conductor. In practice, this phenomenon of ionization of the molecules does not occur homogeneously throughout the volume. We shall see later on (in Chapter 2) that ionization phenomena can lead to the breakdown of the material at values of the macroscopic electrical field that are far less than the critical value mentioned above.

The value of the breakdown field strength is one of the most important characteristics of the insulator. It goes without saying that in practice, we allow ourselves a significant safety margin. The maximum field is generally expressed in [MV.m−1] (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Dielectric strength under direct current (DC) of a number of insulators, expressed in [MV.m−1], with a thickness of around a [mm] at 25°C

The values encountered in practice are highly variable depending on the impurities: transformer oil contaminated with a little water vapor has a strength (or “rigidity”) of 15 [MV.m−1]; when perfectly free of water, this value can reach up to 500 [MV.m−1]. The “vacuum” itself is not a perfect insulator: with a field strength of around 100 [MV.m−1], the negative charges are torn away from metals – a phenomenon which is greatly facilitated by an increase in temperature (thermo-electronic effect) and by light (photoelectric effect).

In addition, ionization may be caused by friction (triboelectric effect), X-rays and particle/molecule collisions.

The positive and negative charges into which the insulator molecule is split are called “ions”, which is a Greek word meaning “to walk”. In effect they are charges moving (or “walking”) under the influence of the field, once the spring holding them has been broken.

1.1.3. Polarized dielectrics

Polarization is the characteristic property of dielectrics. Here, we propose loo...