![]()

Part I

Scale, Measurement, Modeling, and Analysis

![]()

2

Scale Issues in Multisensor Image Fusion

Manfred Ehlers and Sascha Klonus

2.1 Scale in Remote Sensing

Scale is a term that is used in many scientific applications and communities. Typical well-known measurement scales are, for example, the Richter scale for the magnitude of earthquakes and the Beaufort scale for wind speed. We speak of large-scale operations if they involve large regions or many people. Cartographers use the term scale for the description of the geometric relationship between a map and real-world coordinates. In remote sensing, scale is usually associated with the latter meaning the map scale for typical applications of remote sensors. To a large degree, scale is dependent on the geometric resolution of the sensor which can be measured in ground sampling distance (GSD). The GSD is usually the same or similar to the final pixel size of the remote sensing data set. In addition to the GSD, scale is also associated with the level and quality of information that can be extracted from remotely sensed data.

Especially with the launch of the first SPOT satellite with independent panchromatic and multispectral sensors, it became evident that a combined analysis of the high-resolution panchromatic sensor and the lower resolution multispectral images would yield better results than any single image alone. Subsequently, most Earth observation satellites, such as the SPOT and Landsat series, or the very high resolution (VHR) sensors such as IKONOS, QuickBird, or GeoEye acquire image data in two different modes, a low-resolution multispectral and a high-resolution panchromatic mode. The GSD or scale ratio between the panchromatic and the multispectral image can vary between 1 : 2 and 1 : 8 with 1 : 4 the most common value. This ratio can even become smaller when data from different sensors are used, which is, for example, necessary if satellite sensors with only panchromatic (e.g., WorldView-1) or only multispectral (e.g., RapidEye) information are involved. Consequently, efforts started in the late 1980s to develop methods for merging or fusing panchromatic and multispectral image data to form multispectral images of high geometric resolution. In this chapter, we will investigate to what degree fusion techniques can be used to form multispectral images of larger scale when combined with high-resolution black-and-white images.

2.2 Fusion Methods

Similar to the term scale, the word fusion has different meanings for different communities. In a special issue on data fusion of the International Journal of Geographical Information Science ( IJGIS ), Edwards and Jeansoulin (2004, p. 303) state that “data fusion is a complex process with a wide range of issues that must be addressed. In addition, data fusion exists in different forms in different scientific communities. Hence, for example, the term is used by the image community to embrace the problem of sensor fusion, where images from different sensors are combined. The term is also used by the database community for parts of the interoperability problem. The logic community uses the term for knowledge fusion.”

Consequently, it comes as no surprise that several definitions for data fusion can be found in the literature. Pohl and van Genderen (1998, p. 825) proposed that “image fusion is the combination of two or more different images to form a new image by using a certain algorithm.” Mangolini (1994) extended data fusion to information in general and also refers to quality. He defined data fusion as a set of methods, tools and means using data coming from various sources of different nature, in order to increase the quality (in a broad sense) of the requested information (Mangolini, 1994). Hall and Llinas (1997, p. 6) proposed that “data fusion techniques combine data from multiple sensors, and related information from associated databases.” However, Wald (1999) argued that Pohl and van Genderen's definition is restricted to images. Mangolini's definition puts the accent on the methods. It contains the large diversity of tools but is restricted to these. Hall and Llinas refer to information quality in their definition but still focus on the methods.

The Australian Department of Defence defined data fusion as a “multilevel, multifaceted process dealing with the automatic detection, association, correlation, estimation, and combination of data and information from single and multiple sources” (Klein, 2004, p. 52). This definition is more general with respect to the types of information than can be combined (multilevel process) and very popular in the military community. Notwithstanding the large use of the functional model, this definition is not suitable for the concept of data fusion, since it includes its functionality as well as the processing levels. Its generalities as a definition for the concept are reduced (Wald, 1999). A search for a more suitable definition was launched by the European Association of Remote Sensing Laboratories (EARSeL) and the French Society for Electricity and Electronics (SEE, French affiliate of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) and the following definition was adopted in January 1998: “Data fusion is a formal framework in which are expressed means and tools for the alliance of data originating from different sources. It aims at obtaining information of greater quality; the exact definition of ‘greater quality’ will depend upon the application” (Wald, 1999, p. 1191).

Image fusion forms a subgroup within this definition, with the objective to generate a single image from multiple image data for the extraction of information of higher quality (Pohl, 1999). Image fusion is used in many fields such as military, medical imaging, computer vision, the robotics industry, and remote sensing of the environment. The goals of the fusion process are multifold: to sharpen multispectral images, to improve geometric corrections, to provide stereo-viewing capabilities for stereo-photogrammetry, to enhance certain features not visible in either of the single data sets alone, to complement data sets for improved classification, to detect changes using multitemporal data, and to replace defective data (Pohl and van Genderen, 1998). In this article, we concentrate on the image-sharpening process (iconic fusion) and its relationship with image scale.

Many publications have focused on how to fuse high-resolution panchromatic images with lower resolution multispectral data to obtain high-resolution multispectral imagery while retaining the spectral characteristics of the multispectral data (e.g., Cliche et al., 1985; Welch and Ehlers, 1987; Carper et al., 1990; Chavez et al., 1991; Wald et al., 1997; Zhang 1999). It was evident that these methods seem to work well for many applications, especially for single-sensor, single-date fusion. Most methods, however, exhibited significant color distortions for multitemporal and multisensoral case studies (Ehlers, 2004; Zhang, 2004).

Over the last few years, a number of improved algorithms have been developed with the promise to minimize color distortion while maintaining the spatial improvement of the standard data fusion algorithms. One of these fusion techniques is Ehlers fusion, which was developed for minimizing spectral change in the pan-sharpening process (Ehlers and Klonus, 2004). In a number of comprehensive comparisons, this method has tested superior to most of the other pan-sharpening techniques (see, e.g., Ling et al., 2007a; Ehlers et al., 2010; Klonus, 2011; Yuhendra et al., 2012). For this reason, we will use Ehlers fusion as the underlying technique for the following discussions. The next section presents a short overview of this fusion technique.

2.3 Ehlers Fusion

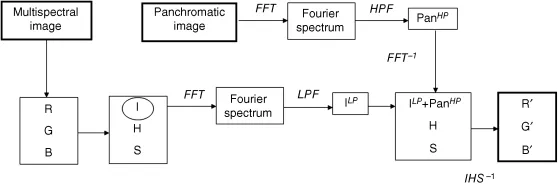

Ehlers fusion was developed specifically for spectral characteristic-preserving image merging (Klonus and Ehlers, 2007). It is based on an intensity–hue–saturation (IHS) transform coupled with a Fourier domain filtering. The principal idea behind spectral characteristic-preserving image fusion is that the high-resolution image has to sharpen the multispectral image without adding new gray-level information to its spectral components. An ideal fusion algorithm would enhance high-frequency changes such as edges and gray-level discontinuities in an image without altering the multispectral components in homogeneous regions. To facilitate these demands, two prerequisites have to be addressed. First, color information and spatial information have to be separated. Second, the spatial information content has to be manipulated in a way that allows an adaptive enhancement of the images. This is achieved by a combination of color and Fourier transforms (Figure 2.1).

For optimal color separation, use is made of an IHS transform. This technique is extended to include more than three bands by using multiple IHS transforms until the number of bands is exhausted. If the assumption of spectral characteristic preservation holds true, there is no dependency on the selection or order of bands for the IHS transform. Subsequent Fourier transforms of the intensity component and the panchromatic image allow an adaptive filter design in the frequency domain. Using fast Fourier transform (FFT) techniques, the spatial components to be enhanced or suppressed can be directly accessed. The intensity spectrum is filtered with a low-pass (LP) filter whereas the spectrum of the high-resolution image is filtered with an inverse high-pass (HP) filter. After filtering, the images are transformed back into the spatial domain with an inverse FFT and added together to form a fused intensity component with the low-frequency information from the low-resolution multispectral image and the high-frequency information from the high-resolution panchromatic image. This new intensity component and the original hue and saturation components of the multispectral image form a new IHS image. As the last step, an inverse IHS transformation produces a fused RGB image that contains the spatial resolution of the panchromatic image and the spectral characteristics of the multispectral image. These steps can be repeated with successive three-band selections until all bands are fused with the panchromatic image. The order of bands and the inclusion of spectral bands for more than one IHS transform are not critical because of the color preservation of the procedure (Klonus and Ehlers, 2007). In all investigations, the Ehlers fusion provides a good compromise between spatial resolution enhancement and spectral characteristics preservation (Yuhendra et al., 2012), which makes it an excellent tool for the investigation of scale and fusion. Fusion techniques to sharpen multispectral images have focused primarily on the merging of panchromatic and multispectral electro-optical (EO) data with emphasis on single-sensor, single-date fusion. Ehlers fusion, however, allows multiple-sensor, multiple-date fusion and has recently been extended to fuse radar and EO image data (Ehlers et al., 2010). Consequently, we will address scale-fusion issues for multisensor, multitemporal EO image merging as well as the inclusion of radar image data as a “substitute” for panchromatic images.

2.4 Fusion of Multiscale Electro-Optical Data

2.4.1 Data Sets and Study Site

For our investigation, we selected a study area in Germany representing a part of the village of Romrod (Figure 2.2). This area was chosen because it contained several important features for fusion quality assessment such as agricultural lands (fields and grasslands), man-made structures (houses, roads), and natural areas (forest).

It was used as a control site of the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission (JRC) in the project “Control with Remote Sensing of Area-Based Subsidies” (CwRS) (http://agrifish.jrc.it/marspac/DCM/). A series of multitemporal multispectral remote sensing images were available for this site and formed the basis for our multiscale fusion investigation (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Multisensor Remote Sensing Dat...