- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This title is an essential primer for all students who need some background in microbiology and want to become familiar with the universal importance of bacteria for all forms of life.

Written by Gerhard Gottschalk, Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology and one of the most prominent microbiologists in our time, this text covers the topic in its whole breadth and does not only focus on bacteria as pathogens.

The book is written in an easy-to-read, entertaining style but each chapter also contains a `facts' section with compact text and diagrams for easy learning. In addition, more than 40 famous scientists, including several Nobel Prize winners, contributed sections, written specifically for this title. The book comes with color figures and a companion website with questions and answers.

Key features:

- Unique, introductory text offering a comprehensive overview of the astonishing variety and abilities of Bacteria

- Easy-to-read, fascinating and educational

- Written by one of the best known microbiologists of our time

- Color images throughout

- Each chapter has a compact tutorial part with schemes on the biochemistry and metabolic pathways of Bacteria

- Comes with a companion website with questions and answers

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Discover the World of Microbes by Gerhard Gottschalk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias biológicas & Microbiología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Reading Section

Chapter 1

Extremely Small But Incredibly Active

It is the greatest dream of a bacterial cell

to become two bacterial cells

to become two bacterial cells

François Jacob

A visit to our Department of Microbiology was on the agenda of a high-ranking politician. How to impress him? We started with the smallness of bacteria but not in the usual way by stating that bacteria are approximately 1 µm long, so 1000 bacterial cells lined up end-to-end would measure just 1 mm. We tried a different way:

“Sir, this test tube contains nearly 6.5 billion bacterial cells in a spoonful of water. Thus, the number of bacteria nearly equals the number of human beings on our planet.” He took the test tube, looked at it, and could hardly recognize the slight turbidity. One billion bacterial cells in one ml or 1000 billion cells in a liter are barely visible. Then we pulled out a photograph the size of a letter pad and said, “Here are two of these 6.5 billion cells (Figure 1).” The Minister was impressed with the smallness of bacteria, which makes them barely visible even in large numbers, and with the enormous power of the methods used to examine them, for example, electron microscopy.

Figure 1 Test tube with a suspension of 6.5 billion bacteria, of which two are shown in an electron micrograph. The cell on the right has nearly completed cell division. The flagellae (long thread-like structures) provide motility to the cells.

(Source: Frank Mayer and Anne Kemmling, Goettingen, Germany.)

Electron Microscopy? I Used a Light Microscope When I Was at School, But What Is the Principle Behind the Electron Microscope?

Let’s have the expert Frank Mayer (Goettingen, Germany) tell us about this:

“Well, the “light” required for electron microscopy is a beam of electrons. This one is invisible to our eyes, but the pictures produced can be made visible. Because of the shorter wavelength of electron beams, much smaller details of biological objects can be seen than by light microscopy. Even enzyme molecules can be made visible, for example, on photographic paper. The disadvantage of using electrons is that a vacuum is required. Therefore, water has to be removed from samples before they can be examined, and this may cause damage to the objects. But recent improvements in electron microscopy make it possible to avoid damage to the objects by removing water from the objects in the frozen state.”

Isn’t it fascinating that electron microscopy makes it possible to magnify objects 100 000 times? Even light microscopy is capable of enlarging objects 1000-fold. This already impressed the plant physiologist Ferdinand Cohn (1828–1898), who wrote,

“If one could inspect a man under a similar lens system, he would appear as big as Mont Blanc [in the Alps] or even Mount Chimborazo [in Ecuador]. But even under these colossal magnifications, the smallest bacteria look no larger than the periods and commas of a good print; little or nothing can be distinguished of the inner parts and of most of them their very existence would have remained unsuspected if it had not been for their countless numbers.”

Ferdinand Cohn obviously exaggerated somewhat: a man two meters tall magnified 1000 times would be two thousand meters (6600 feet) tall, nearly half the elevation of Mont Blanc and one third that of Mount Chimborazo.

It is difficult to imagine that clear water can actually be highly contaminated, or that one cubic meter of air can contain one thousand microbial cells. Air, of course, is only slightly inhabited by microorganisms, but it is different when we look at our skin, which is densely populated by bacterial cells (see Chapter 10) with amazing biological activities. There are many sites in nature where they are able to multiply rapidly. Escherichia coli (E. coli, for short) resides in our intestine and is able to divide every 20 minutes! To put it casually, if one trillion bacterial cells in my intestine go with me to the movies, and if they manage to grow and divide optimally, then 16 trillion cells will leave the cinema with me 80 minutes later.

Good Example, But Why Do Bacteria Multiply So Astonishingly Fast?

It’s because bacteria have a high metabolic activity due to their high surface-to-volume ratio. Let me give you an example: If we put a cube of sugar into a glass of tea and, at the same time, the same amount of table sugar into a second glass, the table sugar will dissolve faster than the cube of sugar. Its surface-to-volume ratio is larger. A cube with an edge length of 1 cm has a surface-to-volume ratio of 6 : 1, between the total surface area of the sides, 6 cm2, and the total volume, 1 cm3. If we cut the cube into “bacteria-size” cubes with an edge length of 1 µm, we would end up with 100 million cubes with an overall surface area of 60 000 cm2. The total volume would be the same but the surface-to-volume ratio would increase by a factor of 10 000.

That has its consequences. Compared to cells of higher organisms, bacteria have a much larger surface area at their disposal, allowing the faster import of nutrients and export of waste products. Therefore, cell constituents can be synthesized more rapidly, a prerequisite for the rapid multiplication of cells. That’s why bacteria have the highest multiplication rates: some species have a record of around 12 minutes, so every 12 minutes two cells emerge from one. This, of course, cannot be generalized. There are also slow-growing bacteria that divide every 6 hours or even once every few days. Bacteria living in the “land of milk and honey” grow and divide rapidly, whereas the organisms in nutrient-deficient habitats such as oceans are much slower when it comes to cell division.

The Ability of Bacterial Cells to Divide Every 20 Minutes, or Even Every 12 Minutes, Is Quite Impressive. What Does that Mean for a Bacterial Population?

Let’s look at a single bacterial cell multiplying every 20 minutes under optimal conditions. How many cells and how much cell mass would be produced after 48 hours? We have to do some simple calculations. One cell (20) would give rise to two cells (21) after 20 minutes; four cells (22) after 40 minutes; and eight cells (23) after 60 minutes. Three divisions per hour would make a total of 144 divisions in 48 hours, resulting in a total of 2144 cells. This number probably doesn’t impress you. Let’s do a few more calculations: Conversion into a common logarithm (144 × 0.3010), with 10 as a base, yields 1043 cells. The weight of one bacterial cell is around 10−12 g, so 1043 cells weigh 1031 g or 1025 tons. Our planet weighs 6 × 1021 tons, so after 48 hours the total bacterial mass would be nearly 1000 times that of our planet.

Very Impressive, But Certainly Not Realistic.

Of course not, but the calculation is correct. However, the assumption that cells would divide every 20 minutes for a period of 48 hours is incorrect. Nutrients would have become limited after a few hours, so growth would have slowed down and stopped eventually. Perhaps the situation can be compared to that of a large pumpkin, which after reaching a critical size will also stop growing because of shortage of nutrients and accumulation of metabolic byproducts.

I Have Learned Something New. I Would Like to Know How Bacteria Compare with Higher Organisms.

Chapter 2

Bacteria Are Organisms Like You and Me

Nature would not invest herself in such

shadowing passion without some instruction

shadowing passion without some instruction

William Shakespeare, Othello

But What About Archaea and Viruses?

Archaea, to be introduced in Chapter 3, are living organisms like bacteria, but viruses aren’t like them at all because several characteristic features are missing. Viruses look and often act like little golf balls, just lying around or flying through the air. They aren’t able to do much by themselves. But as soon as they have entered a host cell, they start their devilish work. Viruses are able to cause epidemics, so they must somehow have life in them (see Chapter 30).

Bacterial and archaeal cells actually have much in common with plant and animal cells. Of course, you can’t compare a single-celled organism such as our intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli with an oak tree or an elephant. Comparisons have to be made at eye level, for example, comparing an E. coli cell with a cell from an oak leaf or with a muscle cell from an elephant. Then, the features common to all cells will become apparent. Let’s first look at the cell constituents.

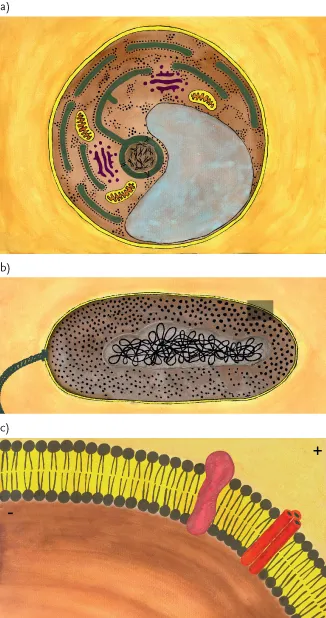

All cells contain DNA (DeoxyriboNucleic Acid), but there is one qualitative difference. The DNA in plant and animal cells is localized in the nucleus, a compartment surrounded by a membrane. Plants and animals are therefore called eukaryotic organisms. A simple eukaryotic cell, the yeast cell, is depicted schematically in Figure 2a. Bacteria, on the other hand, are prokaryotic organisms whose DNA more or less floats in the cytoplasm (Figure 2b), which is a sort of gel. This intracellular space contains many proteins, nucleic acids, amino acids, vitamins, and salts.

Figure 2 The eukaryotic and the prokaryotic cell. (a) The eukaryotic cell contains a nucleus (center) surrounded by a membrane (with pores), a vacuole (light blue), the endoplasmatic reticulum (green), the Golgi-apparatus (purple), mitochondria (yellow/orange), ribosomes (black dots) and cytoplasm. The cell is surrounded by a cytoplasmic membrane and a cell wall. Diameter of the yeast cell depicted: 10 µm. (b) The prokaryotic cell contains a circular, coiled-up chromosome; ribosomes; and cytoplasm. The cell is also surrounded by a cytoplasmic membrane and a cell wall. A flagellum is depicted on the left (not present in all bacteria). Bacterial cells have an average length of 1 µm. (c) The cytoplasmic membrane consists of a phospholipid bilayer. In living organisms the membrane is charged, negative inside and positive outside. Proteins (red) are inserted into the membrane.

(Watercolor and gouache: Anne Kemmling, Goettingen, Germany.)

All cells contain three types of RNA (RiboNucleic Acid). The ribosomal RNA, together with the ribosomal proteins, makes up the ribosomes, the protein synthesis factories of the cells. The second type is messenger RNA which transmits DNA-imprinted messages to the protein synthesis factory. Messenger RNA passes the instructions from the DNA to the ribosomes, where proteins are synthesized on the basis of these instructions. There are mechanisms to ensure that only those proteins are synthesized that are required under certain physiological conditions. Not all proteins encoded on the DNA are continuously needed. The third type of RNA, transfer RNA, is required for the alignment of amino acids to form proteins. Each cell contains at least 20 of these transfer RNAs, which are specific for the 20 amino acids present in proteins. According to the synthesis protocol of the messenger RNA, the transfer RNAs, each linked to a respective amino acid, are lined up in the prescribed order then the amino acids are connected.

In all cells the entire machinery discussed above is surrounded by the cytoplasmic membrane, which is negatively charged on the inside and positively charged on the outside (Figure 2c). The membrane contains checkpoints for the transport of materials into the cells. These transport processes are highly specific; for example, there are checkpoints that allow potassium ions to pass but not sodium ions. The interior of most bacteria is high in potassium ions but low in sodium ions. If we were somehow able to taste the interior of a bacterium from the ocean (intracellular volume around 1 µm3, 1 cubic micrometer), it wouldn’t taste salty. Without its charge, the cytoplasmic membrane would be unable to fulfill its functions to ensure that the composition of the cell’s interior differs dramatically from the surrounding fluid. Inside the cell there are favorable conditions for cell division, irregardless of the conditions outside. The cytoplasmic membrane and its functions is one of the greatest miracles of evolution. How the membrane is charged will be described in Chapter 8.

Those Are the Cell Constituents, But How Does One Cell Become Two Cells?

To answer this question we have to look at the processes of life at a cellular level. Which processes are involved when two cells are formed from one? As already discussed, DNA is the carrier of genetic information needed to generate two E. coli-cells from one E. coli-cell. First of all, energy is required for the generation of a new cell. Here, the magic word is ATP, the abbreviation for adenosine-5′-triphosphate. ATP is the energy currency of all organisms on our planet. It powers processes such as thinking or muscle work, also growth, motility, and reproduction in bacteria. When ATP fulfills its role as an energy source, it is at the same time devaluated; it loses one phosphate residue, and adenosine-5′-diphosphate (ADP) is formed. This conversion is coupled with a release of chemical energy that can be invested in the energy-requiring reactions mentioned above.

Before a cell can divide into two cells, the chemical constituents of the cell have to be synthesized. It is as if a completely furnished house is to be converted into a completely furnished duplex. The “furniture” has to be assembled and set up or installed, so that two viable cells will have been formed from one. If we disregard the membrane, the cell wall, and any reserve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Prolog

- Part One: Reading Section

- Part Two: Study Guide

- Appendix A Selected literature

- Appendix B Glossary

- Appendix C Subject index of figures and tables

- Credits

- Index