![]()

1

Input Factors Affecting Profitability: a Changing Paradigm and a Challenging Time

Jason K. Ahola and Rodney A. Hill

Introduction

Since their creation in the 1960s, US beef cattle improvement programs have predominantly focused on improving output-related traits through genetic selection of beef seedstock cattle. Such traits historically included economically relevant weight and carcass traits by much of the seedstock industry and, more recently, fertility traits by a few select breed associations. However, during that time almost no emphasis was placed on cost-related traits, including feed intake, feed efficiency, and/or feed utilization associated with the output traits, based on the absence of genetic predictions for these traits by US beef breed associations (Rumph, 2005). The apparent lack of interest in selecting cattle based on economically relevant cost traits has probably been due to relatively low-priced feed inputs (at least up until late 2006) and high costs associated with individually measuring feed intake in cattle.

Because of inherent physiological differences, beef cattle are less efficient at converting grain to meat protein than other meat animal species (e.g., pork, poultry), thus each pound of beef protein requires a higher proportion of feed energy to produce it (Ritchie, 2001). Dickerson (1978) estimated that of all the dietary energy required to produce beef, only 5% is used for protein deposition in progeny that are slaughtered. Granted, most of the life-cycle energy used by beef cattle is acquired via forages unusable by monogastrics. However, the beef industry's efficiency is unfavorable when compared to 14% and 22% of dietary energy going to protein deposition in slaughter progeny in the pork and poultry production industries, respectively.

As a result, beef producers began to recognize the importance of identifying cattle that are genetically superior at converting feedstuffs to pounds of meat product. However, Ritchie (2001) pointed out that it's unreasonable for beef producers to expect to achieve the feed efficiency levels of competing monogastric species. Significant changes started to occur when feed prices began increasing in late 2006 when the US beef seedstock industry began a genetic evaluation program for feed intake and efficiency (BIF, 2010). It is assumed that this was caused by the fact that feed is the largest variable cost associated with the production of beef. Such genetic evaluation programs included the development of a uniform set of procedures for collecting individual feed intake data on seedstock cattle during a postweaning growth phase for use in the development of genetic predictions for feed intake and efficiency (BIF, 2010). A more comprehensive description of the feed intake guidelines being used by scientists working in genetic improvement of feed efficiency is presented in Chapter 2. However, it remains unclear how quickly and aggressively beef producers will increase emphasis on the importance of selecting for improved feed efficiency. If effective improvement in feed efficiency is to occur through genetic selection strategies, it is necessary for the industry to routinely collect raw feed intake data, to use these data to develop genetic predictions, and to incorporate predictions into selection programs.

Influence of Input and Feed Costs on the Beef Production Industry

Profitability within the beef production system requires maximizing outputs (revenues) while minimizing inputs (costs). The profitability equation can be denoted as:

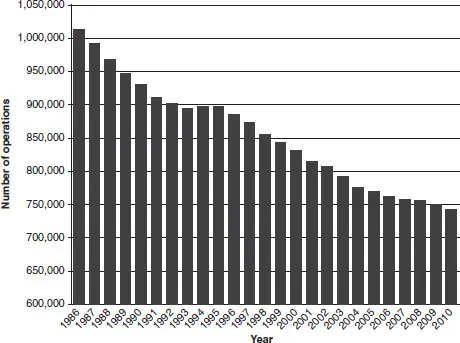

Profitability of cow/calf producers has become a concern within the US beef industry, based on the consistent loss of cow/calf producers from the industry. From the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, nearly a quarter million cow/calf producers left the industry—approximately 9,000 per year (Figure 1.1).

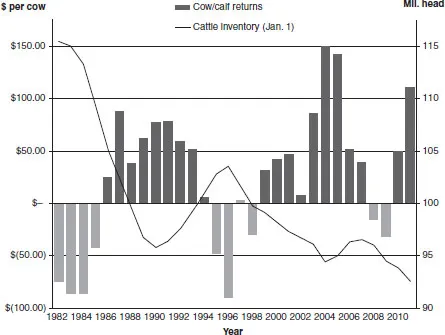

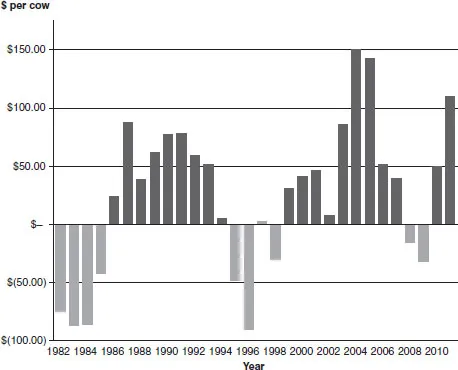

Historically, cow/calf profitability was driven more by the revenue side of the profitability equation than the cost side. This can be seen in the comparison of estimated cow/calf returns with total cattle inventory from 1982 to 2011 (Figure 1.2). Prior to 2006, the average cow/calf producer was consistently unprofitable (light gray bars) during times when the US cattle inventory was near a peak (thin black line), due to a reduction in income resulting from an oversupply of calves and beef in the marketplace and thus lower cattle prices. Conversely, the average cow/calf producer was profitable (dark gray bars) when cattle inventory was relatively low, primarily due to higher calf prices caused by a reduced supply of calves to feedyards. However, beginning in 2006, this strong relationship between cow/calf profitability and total cattle inventory weakened. This can be seen in cow/calf profitability that was concurrent with peak inventory during 2006 and 2007. Since that time, financial losses during 2008 and 2009 have been attributed to elevated input costs.

As the predominant driver of cow/calf profitability moves from primarily supply and demand (and the historical “cattle cycle”) and more toward input costs, the importance of evaluating beef production as a system becomes vital. Massey (1993) provided a sound synopsis of the importance of the “systems concept” of beef production in a Beef Improvement Federation Fact Sheet. He stated that the historical emphasis on increasing production (e.g., milk, gain, mature size) by performance-oriented seedstock and commercial cow/calf producers did not result in a parallel increase in profit over time. Those producers failed to consider additional aspects in the decision-making process for their operation—as would have otherwise been done within a systems approach where more than just outputs are included. Massey (1993) further stated that “overall efficiency of the enterprise—in other words, net return …” should be the most important consideration by a beef cattle operation. A true system should include all components that influence net return, including cost. The general absence of vertical integration within the beef industry, particularly at the cow/calf level, contributes to the beef industry's multifactorial production system. This has generally led cow/calf producers to be less likely to consider a systems approach in their decision-making process.

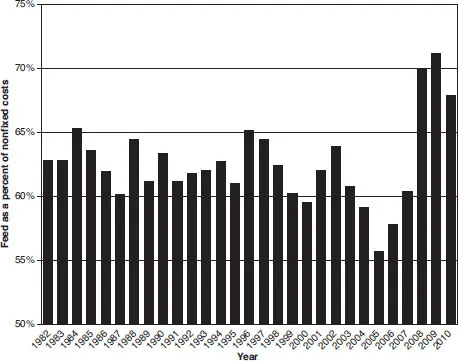

A great opportunity for cow/calf producers to reduce costs is through feed inputs. The USDA Economic Research Service reported that feed-associated costs have represented 56–71% of all nonfixed (operating) expenses on US cow/calf producers from 1982 to 2010 (Figure 1.3). The average percentage of 65.4% during 2006 to 2010, when feed prices were elevated above historical levels, is noticeably higher than the previous average of 62.0% from 1982 to 2005. In addition to comprising a larger percentage of nonfixed costs in recent years, the amount that feed-associated costs made up has been more volatile (both the lowest and highest percentages occurred within the 5-year period from 2005 to 2009).

It has been estimated that 55 to 75% of total costs associated with beef cattle production are feed related (NRC, 2000), suggesting that emphasis on improving feed efficiency in beef cattle is a tremendous opportunity for producers (Lamb et al., 2011). Additionally, more than half of the feed required by the US beef production industry is utilized by the breeding cowherd, compared to their progeny, which are fed out until harvest (Carstens and Tedeschi, 2006; Lamb et al., 2011). Because of the large amount of animal-to-animal variation present in the maintenance energy (ME) requirements among cattle (Johnson et al., 2003), selection for feed efficiency is logical.

Beyond native range and improved grass pastures, harvested feedstuffs serve as the primary feed inputs for most of the US beef industry: hay (grass and alfalfa) for the breeding cowherd and corn for feedyard cattle. Corah (2008) identified major challenges facing the US beef industry and its infrastructure of corn feeding. Historically, the US feedyard industry has evolved in an environment in which both energy and corn have been relatively inexpensive. Since 2006, these conditions appear to have begun to change and the trend may be one that will be a permanent and an ever-increasing challenge that must be faced and addressed by the industry.

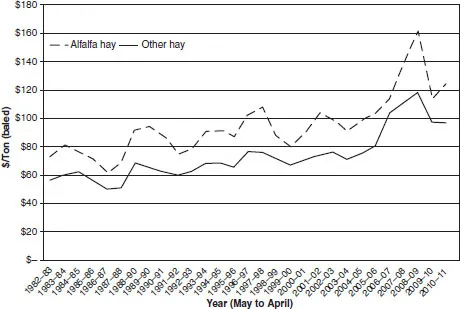

According to USDA-NASS data, prices for alfalfa and other hay increased gradually but steadily for a 30-year period until 2006 (Figure 1.4). However, the rate of price increase, and associated volatility, increased dramatically in late 2006.

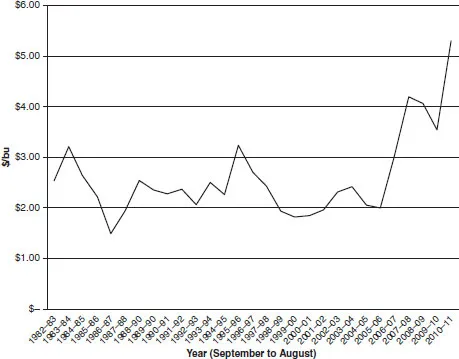

Much of the increase in hay price has been driven by elevation in corn price. During the same time period, the per-bushel price of corn actually remained flat, although somewhat volatile, until 2006 (Figure 1.5).

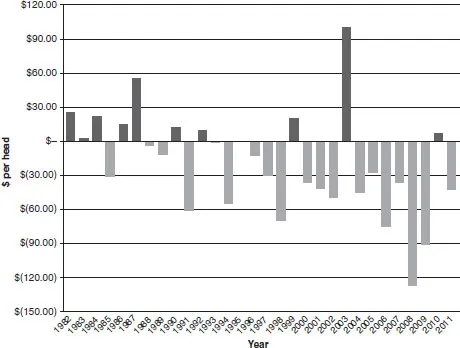

As the primary component of feedyard diets, the price of corn has influenced feedyard cost-of-gain based on summarized data by Kansas State University (Figure 1.6).

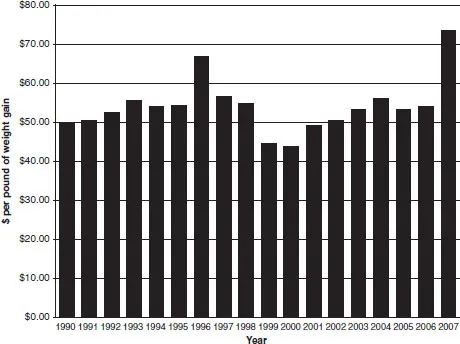

A discussion of historical profitability in the cow/calf and feedyard sectors, as well as main drivers of profitability, will help to clarify the importance of feed efficiency to the beef industry. As discussed earlier, cow/calf profitability during the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s generally responded to the cattle cycle and total inventory of cattle in the United States. On the basis of the cow/calf estimates reported in Figure 1.7, after significant losses occurred in the early 1980s, short periods of sustained profitability occurred from 1986 to 1994 and from 1999 to 2007. These periods were interrupted by short periods of losses during the mid-1990s and 2007 to 2008.

To determine the key factors that have affected cow/calf profit, Miller et al. (2001) used standardized performance analysis data to evaluate several variables that may affect profitability (measured as return to unpaid labor and management per cow (RLM)). The researchers used data from 225 cow/calf producers in Iowa and Illinois collected from 1996 to 1999. Using a correlation analysis, it was determined that feed cost was the largest factor influencing return to RLM compared to 12 other economic and production traits and in two models explained 52% and 57% of the variation in profit. Further, the authors reported that factors associated with cost explained mo...