![]()

1

General Topics

![]()

1.1

How to Use this Book

I want you the reader to be a good, if not great, problem solver. Problem solving is what engineers do, and it represents your value to society. When a client or employer pays for an engineer’s services, they are purchasing a solution to their problems. Often this process is called designing, investigating or analyzing, but in the end it all comes down to solving a problem or a series of problems.

Engineering problems involving geotechnical issues are difficult to solve, primarily because geotechnical parameters are difficult to measure, difficult to characterize and difficult to analyze. Some of the geotechnical difficulty comes from spatial variability in a large volume of soil on a building site. Some of the geotechnical problem is due to correlating field and/or laboratory measurements to the soil parameters required for analysis, and some of the problem is associated with limitations of analysis methods. I want to help you figure out how to solve geotechnical problems, and I want you to enjoy the problem-solving process.

I want to be your personal mentor, and if you have a mentor, I want to help them mentor you. If you are a student, I want you to start thinking about what is required to become a practicing engineer and to start now to develop the problem-solving tools you need.

Right from the start, I want you to accept the fact that you will never be able to include all of the physical processes involved in natural systems in your model of reality. You have to simplify real-world problems by use of models that have a few essential parameters, or, to use mathematical terminology, you need to limit the number of variables included in your models (equations). Later, in Section 1.2, I will discuss and explain the phenomenon of increasing complexity. Let’s just say for now that you will need to know how to adjust the number of variables considered in your problem-solving efforts to fit the needs of your particular problem.

Speaking of adjustment of the number of variables considered in your engineering problems brings me to a rather thorny engineering management problem that frequently arises between problem-solving engineers and project managers. Before starting to work on the solution of an engineering problem, there needs to be agreement between the engineer and the manager on the level of detail and complexity to be included in the planned analyses. If the project manager thinks that the problem at hand is a simple issue, and you perform a highly complex analysis without informing the project manager, he or she will be unpleasantly surprised. There is going to be an issue over your charging excessive analysis hours to the project manager’s budget. Fights over man-hour budgets for engineering analysis tasks versus the actual number of man-hours expended to solve the problem are quite common in consulting engineering practice these days. Matching the complexity of an engineering investigation and analysis to the requirements of the problem is called applying the “graded approach .” I will give you more information about the graded approach to problem solving in Section 1.3.4, and don’t worry, we will include a discussion of how to handle surprises requiring more work than was initially anticipated.

Unlike most engineering/technical books that you have used, the presentation given here is conversational and personal from me to you. I want to give you practical advice on solving geotechnical problems and give you keys to the use of material that may not have been included in your college work. This “advanced” geotechnical material may be familiar to you, or it may be new; in either case, I want to help you understand the underlying assumptions and limitations of various geotechnical problem-solving techniques. You may not agree with my preferred choices of analytical methods. I would be surprised and a bit suspicious if you did agree with me on everything presented. It is alright to disagree, but we have to agree to base our disagreements on logic and interpretation of physical principles, not on arbitrary preferences. You may conclude that the available data and problem requirements need a more intensive analysis than I suggest is required. That’s fine; if you need to do more detailed analysis work to feel comfortable with the solution, it’s your choice. Just be ready to defend your man-hour charges with your boss, project manager, or client, or come in early or stay late and do the extra work on your own time. Having confidence in your solution to an engineering problem gives a sense of self-satisfaction. Remember that increasing your problem-solving skills increases your personal worth. Please do not think of extra work as giving “the company” something for nothing, consider it as money in your personal problem-solving account. It is your engineering career, not theirs.

During the early part of my career, I was a structural engineer. It was common in an earlier time for geotechnical engineer s to start their careers as structural engineers. My friend Ralph Peck was a famous geotechnical engineer who started as a structural engineer. He had a Ph.D. in structural engineering and no formal degrees in geotechnical engineering. I converted to geotechnical engineering during my graduate studies to help me understand how settlement-induced load redistributions in a structure could lead to structural failure. By the time my Masters degree studies were completed, I was hooked on geotechnical engineering. When I started working as a consulting geotechnical engineer, it quickly became quite clear to me that my structural engineering work had not been a waste. Knowledge of structural engineering helped me communicate with my structural clients because I knew what they needed from their geotechnical consultant. I have included material in this book to help geotechnical engineers understand what structural engineers need for their work, and I’ve tried to clarify geotechnical engineering topics to structural engineers so they can better communicate their project requirements to geotechnical engineers.

I have included what I consider to be important topics on selection and interpretation of soil laboratory tests, on analyses of shallow and deep foundations, retaining structures, slope stability, behavior of unsaturated soils including collapsible and expansive soils, and geotechnical Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD) topics, to name a few. I want you the reader to develop problem-solving tools for each of these geotechnical problems. We will start you with simpler standard practice approaches in each article, and work up to the advanced material. I’ll give you examples of standard practice analysis methods including their assumptions and limitations. I don’t want you to pick a standard practice approach for solving your problem if it doesn’t fit the requirements of your problem! Advanced problem-solving methods are often required to deal with problems that have additional complexity. I do not believe that so-called advanced geotechnical material is only for Ph.Ds. I am convinced that if you graduated from college with a degree in engineering (or science and mathematics), you can use all of the material covered in this book.

In each section of this book, I will give suggested references and include a “Further Reading” section that provides materials for your study and consideration. At the end of each section, I will include a list of the references discussed in the section. I hope you will forgive me, but I do not like to repeat figures and equations from other books. Some equations and discussions are essential and I cannot avoid repeating them, but hopefully with added insights. Over the years I have grown weary of seeing the same material repeated and repeated over and over. I will refer you to the books where these materials are covered, and I hope you will take the opportunity to grow your geotechnical reference library.

It is my goal to help you understand the “how” and “why” of each topic, and to give you tools to use to solve problems that are not always included in text books, but are present in the real world. My advice is that you do not need a geotechnical engineering “cookbook.” What you need is an understanding of geotechnical principles so that you can use them as tools to solve your engineering problems.

![]()

1.2

You Have to See it to Solve it

1.2.1 Introduction to Problem Solving

A question that I am asked by students and 60 year old engineers alike goes something like this, “Why is geotechnical engineering and engineering in general so difficult? When are the codes and requirements going to be simplified like they were in the good old days?” Give me a chance, and I’ll answer these questions, but I need to build my case for the answer.

Did you ever notice that there is one person in the group that almost always disagrees with your opinion, conclusion, report, presentation, problem solution, etc? Sometimes they start by saying, “I’m just a Devil’s Advocate here, but ….” Personally, I don’t want to give the Devil or his attorneys the credit for this phenomena, I believe that skepticism is a natural human trait that at least 10 to 15% of your students, clients, or associates will possess at any given moment. No matter how hard you try to convince these people that you have considered all of the important problem variables, they always seem to come up with new variables for consideration. How do they always manage to complicate your work?

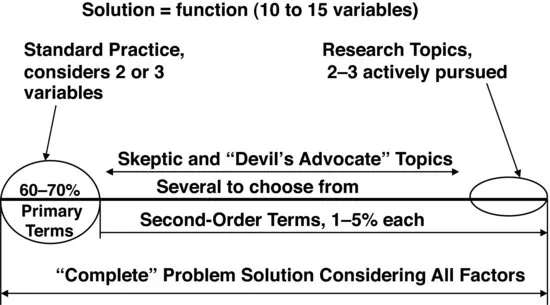

I have come to believe (but cannot prove) that all problems in engineering have at least 10 to 15 variables that could be measured, analyzed, and used in their solution. The ideal or perfect solution to a given problem is a function that considers the impacts and interactions of all of these 10 to 15 variables. This hypothetical perfect solution considers all of the theoretical complexity involved. The engineering profession accepts two to three of these variables as the primary variables required in analysis and design. Analysis based on these two or three variables is referred to as standard practice, see Figure 1.2.1 below.

After removing the primary two to three variables from the solution set, the remaining seven to 13 variables are not considered to be standard practice , and I will call them second-order term s. These second-order terms may not often have a great impact on any given problem, but sometimes they do have significance. When second-order terms are important to the solution of an experienced engineer’s problem, and when he or she has a feel for the magnitude of the impact of these terms is referred to as “experience” or “engineering judgment.”

Thinking of an engineering problem as a number line of issues or variables, such as Figure 1.2.1, helps us to see an aerial view of the problem landscape. On the left end of the scale, say from one to three are the engineering design issues that make up standard practice. Let’s assume that standard practice includes 60 to 70% of the weighted factors of significance . The 30 to 40% that standard practice is off the mark is covered by standard factors such as factors of safety, load factors, resistance factors, and so on. Presumably, standard practice suggests that if you are 60% correct and use a factor of safety of 3.0, or if you are 70% correct and use a factor of safety of 2.5, you should safely bound your problem.

On the right end of the scale in Figure 1.2.1, three issues from the remaining seven to 13 are commonly selected engineering research issues. These second-order terms on the right end of the scale are the habitation of university researchers and professors seeking research funding. If you want to get the problem solved, the design completed, stay in budget and meet your client’s schedule, then you need to stay with the “engineering standard practice analyses” end of the problem scale. If you want a research topic, and you don’t want to cover the same old ground of standard practice variables, then you need to select a second-order variable for study that may prove to be more significant than is currently understood. And finally, if you want to argue with others at conferences and monthly technical meetings, as many skeptics do (and you know who you are), please feel free to bring up issues from the portion of the problem scale that is not considered by standard practice or by current mainline researchers.

1.2.2 Advanced and Expert Practice

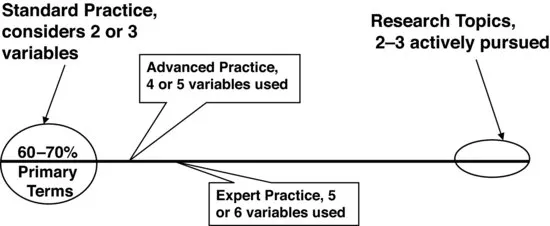

Imagine that a client like a national laboratory, government agency, or high-tech project owner wants you to analyze something out of the ordinary. The measurements, analysis tools and advanced theories required involve something that is not covered by standard design practice. This type of engineering work is often referred to as advanced practice or expert practice. You can see from Figure 1.2.2 that standard practice is bounded by advanced and expert practice. These high-tech practices may be the standard of practice in some other parts of the United States or in other continents outside North America, such as in Europe or Asia. The point is that the definition of standard practice varies from place to place, and it varies with time.

After a natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans on 29 August 2005 or a major failure like the I-35W bridge collapse in Minneapolis on 1 August 2007, standard practice often expands rapidly to deal with issues uncovered during forensic analyses.

1.2.3 Theories Can Be Wrong…

You may say, “Standard practice or the accepted notion of what variables are important can be wrong. What about Albert Einstein and his proof that the standard idea of ether as the element that fills space was wrong?” You ha...