![]()

1

Patients

1.1 Animal Welfare Accounts

Veterinary professionals are concerned about animal welfare. Animal welfare, loosely defined, is about what is good and bad for animals – what is important for them to achieve and what is important for them to avoid. Veterinary work is about achieving states that are good for animals, such as health and enjoyment of life, and avoiding states that are bad, such as pain and illness. So core aims of veterinary work overlap considerably, if not entirely, with animal welfare concerns. This is why many of us chose to train in veterinary science, medicine or nursing and why most of us wanted to work within the profession.

Every person in the world has an effect on animal welfare. How they treat animals they own or meet; what food and clothes they buy; which charities they give money to; what they enjoy as entertainment and their environmental impact can have an effect on the lives of many animals. This effect may be sometimes beneficial. It may also be harmful. Each person probably effects a combination of harm and benefit (even the kindest people do some harm and even the most evil people may help animals by accident) and has an overall impact on animals’ welfare. Each person has an animal welfare account, based on all their welfare impacts. If a person does more harm than good, then they have a negative balance. If a person does more good than harm, this is to their credit.

Those of us in veterinary practice are especially likely to have significant impacts on the welfare of patients and other animals. Sometimes, we have a positive impact by lessening the harms caused by other people or by natural processes such as disease. At other times, we have a negative impact by harming animals or helping other people to harm them. Our veterinary roles provide us with animal welfare capital, which we can use as an investment to do good but which also gives us opportunities to harm animals – just as borrowing against capital can allow people to incur greater debts. Each of us should make our own animal welfare account as healthy and positive as possible.

Having a healthy animal welfare account requires maximising welfare credit and minimising welfare debt. Harms should be minimised wherever possible (just as it is not sensible to borrow more than you need). Some harm may be necessary in order to gain bigger welfare benefits, for example when surgery causes pain but cures the animal of a painful condition (which we can think of as an investment). At other times, welfare benefits can be obtained only by taking certain risks, for example where surgery risks causing neuromas or phantom limb pains (Figure 1.1), and we may have to speculate to accumulate.

This approach suggests that we should make every effort to cause good welfare while avoiding causing harms. We could think of this in terms of our overall impact on animal welfare, a sort of animal welfare footprint. But it seems better to think of it as each leaving a legacy – good or bad – on animal welfare. Veterinary work provides great opportunities to leave a valuable and significant legacy, and this book may provide some additional suggestions to help readers do even more than they already do.

Whether we consider animal welfare to relate to animals’ feelings, their treatment, their biology or their lifestyle, we can be confident that these things are important for animals in some way. This makes veterinary professionals well placed to determine and to achieve animal welfare goals as well. We have an understanding of biological science, interact daily with the pet-owning public and with the animals themselves, and are respected sources of advice in the community. The different people within veterinary practice and professions have different roles and different opportunities to help animals. But we all face similar situations and have the same aims as veterinary professionals.

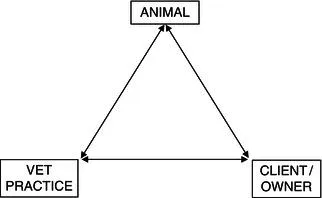

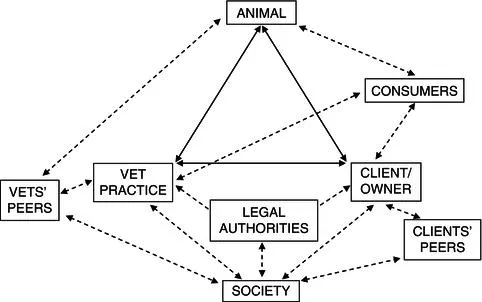

In this role as veterinary professionals, we face a number of pressures and tensions. We see welfare issues every day, and many are recurrences of seemingly unending problems, despite our good work. We are personally involved in and affected by the pressures, tensions and conflicts we experience. These can cause stress, disillusionment and anger. Some people even leave the veterinary professions, and this is both terribly sad for them and a great loss for animals – especially if it is some of the most welfare-concerned people who are vulnerable to these stresses. We have relationships not only with patients but also with clients (Figure 1.2). In many cases, achieving our animal welfare goals helps people. It can help owners who want their animals’ lives, health or behaviour to be improved. It can also help veterinary professionals by reducing the personal and moral stresses and improving profitability. In other cases, we have to balance the conflicting demands. As individual practitioners, we have to balance our wish to achieve our animal welfare goals with client requirements, legal constraints and public concerns. And as professionals, we have to balance being advocates of animal welfare with other goals such as benefitting human society and helping each other. This book looks at how we can best improve animal welfare while respecting these constraints.

We also face conflicts between animals. For example, concern for our patients would lead us to perform caesarians where necessitated by breed conformation. But performing such caesarians perpetuates the problem and allows those conformational traits to continue, leading to increased need for caesarians. In this case, veterinary professionals are both part of the solution and part of the problem. Maintaining a healthy welfare account requires balancing these concerns. In addition, when we do cause harm, either deliberately or through helping our patients, we can improve our welfare account by paying something back. For example, if we perpetuate poor husbandry or breeding (even with the best intentions), then we should offset that harm through proactive efforts to promote better practices.

We can maximise our animal welfare account and solve welfare dilemmas by considering many important issues, including the accountability that veterinary professionals have towards animal welfare (discussed in Sections 1.2 and 1.11), our responsibilities (Sections 1.3 and 1.4), the use of science (Section 1.5) and ideas of what is good for animals (Sections 1.6, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9 and 1.10).

1.2 Animal Welfare Accountability

Veterinary professionals have a special role within society that makes their animal welfare accounts especially important and prominent. During the veterinary profession’s 250 years, it has become increasingly prominent as a force to improve animal welfare and is increasingly held to account for how it treats animals and how animals are treated by society as a whole. Each veterinary professional has a duty to play their part in helping their profession to fulfil its responsibilities to society.

Modern veterinary practice can be traced back to horse marshals’ and farriers’ development of medical treatments and surgical procedures, such as firing, bleeding, castrating and tail-docking. By the eighteenth century, such therapies were routinely applied to cattle, sheep and pigs as rising human populations and breeding strategies made individual animals increasingly valuable.

Veterinary practitioners gained a prominent position in safeguarding animal health, but they were far from a profession. This waited upon scientific and medical developments disseminated through education beginning with the first veterinary course in Lyon in the 1760 s, followed by others in Alfort, Turin, Copenhagen, Vienna, Dresden, Gottingen, Budapest, Hannover, Padua, Skara and London, and later schools in Toronto, Montreal, Ithaca, Iowa, Santa Catalina, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Olinda.

Professional regulation addressed the opportunities for charlatanism (Porter 1992; Hall 1994), with the establishment of professional bodies such as the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in 1844, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) in 1863, the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) in 1949 and the Brazilian “Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária” (CFMV) in 1968. These provided society with a guarantee of knowledge, ability and professionalism.

These developments paralleled changes in society at large that increased the respect for animals. Political changes led to widening social progress and protection of vulnerable groups such as slaves, women and children. Scientific discoveries highlighted the phenotypic and genetic similarities between humans and other animals. Animals began to gain legal protection, with increasingly progressive laws against specific cruel practices, abuse and vivisection.

By the start of the twentieth century, veterinary professionals had a number of societal responsibilities based not only on their key relationships with owners and patients, but on their wider societal relationships with other animals, governments, other veterinary professionals and society at large (Figure 1.3). Alongside veterinary professionals’ primary relationships with animals and clients, the profession also had other vital duties to wider society, such as protecting public health. In addition, the professional status of veterinary practice created new responsibilities for individual practitioners towards their profession and to society.

Since the early twentieth century, there has been a golden age of developments within veterinary science, often paralleling developments in human medicine such as antibiotics, fluid therapy and painkillers and other forms of analgesia. Therapies were often developed on animal experimental subjects, applied to human medical patients, and then adapted to animal medical patients. These developments stimulated the development of veterinary disciplines such as imaging including ultrasound and radiography, immunology to study the bodies’ reactions to disease, epidemiology to study the spread of disease, molecular biology to understand the body on a subcellular level, genetics and chemotherapy.

On the one hand, technological developments allowed higher levels of care and, combined with increased treatment of companion animals (Figure 1.4), increased the transference of techniques and protocols from human medicine. On the other hand, technological developments made it feasible to keep animals in high-production systems. Veterinary professionals could prescribe pharmaceuticals, such as vaccinations and antimicrobials...