![]()

PART I

Principles and Concepts Underpinning the Management of Stress-related Behaviour Problems

![]()

Chapter 1

How Animals Respond to Change

1.1 UNDERPINNING PRINCIPLES RELATING TO STRESS IN COMPANION ANIMALS

1.1.1 STRESS AND CHANGE

It has been said that the only constant in life is change, and it seems that some of us cope better with this than others. In this chapter we will explore why this might be. We will focus on factors that not only affect humans but are also relevant to nonhuman animals. Attempting to adapt to change is an intrinsic part of being alive. As a feature of any living system, the environment changes around us all the time, and we have a number of mechanisms for dealing with this. Two obvious ones that are commonly described in the literature are:

- Physiological processes: Pure changes in physiology are often thought of as being relatively simple (metabolic changes), for example a change in sweating when the body’s temperature starts to rise. These changes may be mediated by either the nervous or the endocrine system, or a combination of both. Often changes in simple physiology are relatively inexpensive, energetically speaking, for an animal to implement.

- Behavioural processes: Behaviour responses, for example an animal panting when it is hot (Figure 1.1), involve much greater use of resources and energy, and so are perhaps better considered as the second line of response in the majority of cases. However, physiological processes are at the root of changes in behaviour too: it is just that behaviour changes are more obvious and involve a shift in the animal’s posture or position.

Sometimes an animal adapts to a stressor by making a mental adjustment (cognitive change), for example accepting something novel in the environment as nonthreatening, and this too is ultimately a reflection of physiological changes in the brain, even though we might focus on the cognitive outcome.

Thus, in response to stress, we can recognise three types of change in the body:

- A metabolic shift.

- A change in behaviour.

- A psychological adjustment.

These are not independent, but rather are usually closely related, though perhaps with one being more obvious than another at a given time, depending on the demands being made or anticipated given the circumstances. Overt changes in behaviour are typically more demanding and are therefore often a secondary line of defence when metabolic shifts are not possible or do not work.

1.1.2 HOMEOSTASIS AND ALLOSTASIS

The concept of homeostasis has dominated thinking about how animals adapt to change for a long time, but in its purest form it has the potential to limit our understanding in some important ways, as we will see. Homeostasis basically means that an animal’s body works to restore an optimal state whenever this is disturbed (stressed). So if blood sugar goes up, the body will try to bring it down again, since high blood sugar can be harmful. An immediate response might be to increase production of insulin in order to increase the uptake of glucose by cells in the body. At a behavioural level, an animal may stop feeding in these circumstances, and at a cognitive level it may no longer show positive interest in cues suggesting food. The concept of homeostasis can be applied not only to stressors associated with internal changes, such as changes in blood sugar, but also to external changes such as unpleasant and dangerous environments or situations that are confusing to the animal: thus, if something scares the animal it may run away in order to restore the preferred state of relaxation in a safe and secure environment. Sometimes an animal must work very hard to restore balance, or it may be frustrated in its efforts by an inescapable situation, such as when a dog wants to get out of a kennel (Figure 1.2).

From these examples, it should be apparent that although responses may share some common features, such as an increase in arousal, stress responses vary according to the nature of the trigger. Thus the specific response is quite different when the trigger is a rise in blood sugar than when it is frustration at a barrier.

The key feature of homeostasis that we will now consider more closely is that the body tries to minimise the impact of stressors (things that disturb us from an optimal set point in some way) by responding to changes. The word ‘responding’ is emphasised as it suggests that it is the disturbance which drives the process. A concern with this idea is that if we provide an animal with a balanced diet, fresh water, an optimal temperature and so on in a nonthreatening environment, we might be tempted to think that the animal should not be stressed. This was one of the errors which led to the belief that factory farming would be good for animals. We now recognise that because animals have evolved in environments in which change inevitably exists, their bodies have come to expect change and so they are driven to do things even when everything seems optimal. This is probably because such a state is never very long-lasting in nature, so there is no evolved mechanism to simply accept that life is good and will remain as such.

An outcome of the evolutionary expectation that life exists within an ever-changing environment is the development of an anticipation of change within the core processes governing the regulation of the body’s metabolism. The body therefore changes in anticipation of change. This is what is meant by the term allostasis, which provides a better model than homeostasis for many physiological processes. The key difference between allostasis and homeostasis is that in allostasis responses are driven by the anticipation of change as well as by actual change. So if an animal is always fed at the same time each day, insulin will eventually be produced at a certain time, even if there is no food available and even if this leads to a significant lowering of blood sugar which the animal then has to counter by producing the antagonistic (opposing) hormone glucagon.

From the preceding example, it might be tempting to think of allostasis as simply a training of the homeostatic response, but it is much more than that, as it helps to explain why animals have natural rhythms to their metabolism and activity even in the absence of cues. It also helps us to understand the wider and changeable psychological needs of animals, which we discuss in the next section.

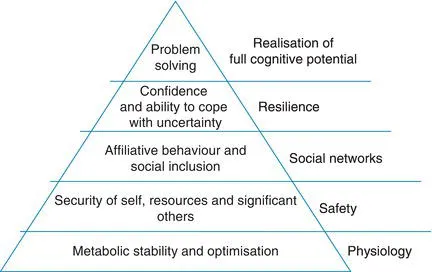

1.1.3 PSYCHOLOGICAL NEEDS

One of the things which many animals do when they have all their fundamental physiological needs met is seek information. There are several reasons why this is useful if there is an inbuilt expectation of change. For example, it allows them potentially to exploit resources more effectively in future (e.g. by knowing where the next meal could come from if the current supply were to dry up) and it might reduce the risk of future harm (e.g. by knowing how strong different potential competitors are). Therefore, when times are good we will often see animals investigate and play much more. Object play allows animals to learn about the physical properties of things, while social play can help them learn about the characteristics of other individuals, including their strengths and weaknesses. An important implication of this is that, in such circumstances, providing for some of these activities should not be considered a luxury, but rather essential for an animal’s well-being. In humans, a hierarchy of needs has been described in the literature by Maslow (1943), which indicates what individuals seek as different needs are met. While some of the higher levels originally described may not be directly applicable to nonhuman animals, this hierarchy can be adapted to give a guide as to animals’ priorities in different circumstances (Figure 1.3).

Another use of this hierarchy is to help us appreciate why an animal is not performing particularly well in a given aspect of its life and what needs to be done to help resolve the issue. For example, an owner might complain that their pet lacks confidence, and this might be at least partly due to unstable social relationships at home, which mean that the animal is focusing resources on social networks as a priority. Without addressing this lower-level need, it may be difficult for the animal to grow in confidence, as its priorities are elsewhere.

This hierarchy indicates that safety or a sense of safety is a big priority for animals after their physiological needs have been met. Most pets are well fed and watered, and so the issue of safety deserves further consideration. Safety broadly means knowing that you can escape potential harm, and so requires that the animal has some freedom to withdraw from situations that it finds unpleasant. In the home, this means the animal has a safe haven, or some other secure attachment. We will return frequently to the importance of providing coping strategies when we discuss the use of pheromones in a clinical context to help animals cope in a variety of settings. The need for safety also helps us to understand why the inappropriate use of punishment, especially by an owner, can be so disruptive to an animal’s well-being. Quite apart from being ineffective in altering the underlying motivation for the unwanted behavioural response and disrupting the bond between the owner and their pet, the inconsistent use of aversive methods leads to the animal’s lacking a sense of safety. Thus common basic requirements for managing almost any behaviour problem are that all punishment should cease and that a healthy relationship between the owner and their pet should be established. Only with these foundations in place can we expect the animal to have the confidence to change inappropriate emotional responses. Once again, pheromones can be useful in this process, as we shall see. However, there are also important constraints on what can be achieved, which are considered in the next section.

1.1.4 THE GENOME LAG AND EVOLUTIONARY CONSTRAINTS

Companion animals evolved in a particular environment over centuries and today often live in a very different one. The modern environment can be very stressful for both humans and their companion animals. The fact that evolution may not have equipped them with the mechanisms to deal with the sorts of stress or that they face in the domestic home can pose a problem. Let us look at the dog as an example: it is a social animal and is adapted to live in close social groups. Hence, being left alone can be very stressful for a dog and it will use the mechanisms that it has received through evolution to cope with this situation, such as howling in order to try to reestablish contact with the members of its group. Other possible behaviours it might attempt include trying to escape from the environment in which it is isolated, which can result in considerable property damage (Figure 1.4). We might think that a dog should know it can’t break through a wall, but solid, all-enclosing walls are not something it has evolved to deal with. An important thing to appreciate here is that although a behaviour may not be very effective (i.e. maladaptive), that does not mean the underlying behavioural control systems are broken (i.e. malfunctional). There is sometimes a tendency to think that a behaviour must be pathological if it does not bring an obvious benefit, but this is not always the case; an animal may simply be using its evolutionary rules of thumb in an inappropriate context because of the artificiality of the environment. This has important implications as it means we should not be looking for treatments to correct a supposed malfunction, but rather we should be looking at the environmental contingencies and perceptions of the animal that are leading it to perform in this way. However, although the response may be a functional one, that is not to say it cannot be problematic or give rise to pathological processes as a result of its inappropriate deployment ...