eBook - ePub

Preservation and Restoration of Tooth Structure

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Preservation and Restoration of Tooth Structure

About this book

Combining the approaches of preventative and restorative dentistry, this is a revised and updated guide to the clinical techniques and procedures necessary for managing tooth disorders and disease.

- Introduces minimally invasive dentistry as a model to control dental disease and then restore the mouth to optimal form, function, and aesthetics

- Contains several student-friendly features, including a new layout, line drawings and clinical photographs to illustrate key concepts

- Covers fundamental topics, including the evolutionary biology of the human oral environment; caries management and risk assessment; remineralization; principles of cavity design; lifestyle factors; choices between restorative materials and restoration management

- Includes a companion website with self-assessment exercises for students and a downloadable image bank for instructors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preservation and Restoration of Tooth Structure by Graham J. Mount, Wyatt R. Hume, Hien C. Ngo, Mark S. Wolff, Graham J. Mount,Wyatt R. Hume,Hien C. Ngo,Mark S. Wolff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dentistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Oral Environment and the Main Causes of Tooth Structure Loss

J. Kaidonis, G.C. Townsend, J. McIntyre, L.C. Richards & W.R. Hume

The human oral environment evolved within a Paleolithic (Stone Age) hunter-gatherer setting, reflecting well over 2 million years of evolution from primate origins of even greater antiquity. The interplay between genes and differing environments over many tens of thousands of generations resulted in various oral adaptations that together provided good oral health and function.

Common themes were evident among Paleolithic groups. First, dentitions showed extensive wear when compared to many modern societies, yet the teeth remained functional. Second, although the diet was generally acidic, erosion and the non-carious cervical lesions that are endemic in current populations were not apparent. Third, oral bacterial biofilms were present, yet the prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease was so low that it could be considered insignificant.

With the advent of farming in human societies about 10,000 years ago and increasingly over the last 400 years, as food manufacture and distribution became more common, changes in our diet have led to profound changes in the oral ecosystem. These changes were sudden from an evolutionary perspective and they have been primarily responsible for the modern oral and many of the systemic diseases now afflicting human populations.

Among those diseases are several that lead to the loss of tooth structure.

The Human Oral Environment in Health

The sialo-microbial-dental complex in a state of balance

The human mouth is centrally involved in the first stages of digestion, as is the case in all species with alimentary canals. The need to chew and swallow a variety of foods in order to survive in different environments caused the evolution of oral and dental tissues, salivary secretions and a unique oral microbial ecology. These elements together can be referred to as the sialo-microbial-dental complex. ‘Sialo’ means to do with saliva. All elements were, until recent centuries, in relative harmony or balance in the great majority of individuals.

Tooth structure, diet, the oral microbial mix, saliva and biofilms1 (dental plaque) are closely associated and interrelated physically, functionally and chemically. Although each is described separately in the sections below, the components have evolved together and function as an integrated system. All contribute to health, and under some circumstances all contribute to disease.

Tooth Structure

Enamel

Dental enamel, the strongest substance in the human body, is a highly mineralized tissue with a well-defined structure. It is formed by the precipitation of crystals of apatite, a compound comprised of calcium, phosphate and other elements, into an extracellular protein matrix secreted by specialized cells called ameloblasts.

The precipitation of apatite is called ‘calcification’ or ‘mineralization’. It commences before the emergence of the tooth in the mouth. The protein matrix dissolves as the crystals grow, leaving a tissue comprised almost entirely of apatite crystals in a unique physical arrangement.

Of central importance to the understanding of the chemical dynamics relating to the inorganic components of tooth structure is the fact that ions can move in and out of apatite crystal surfaces, that is, the crystals can shrink, grow or change in chemical composition, depending on local ionic conditions.

Tooth shape is determined by ameloblast proliferation

Ameloblasts are derived from epithelial cells of the embryonic mouth. In a process that is closely controlled genetically, they proliferate into underlying tissue to create the enamel organ, which has a shape or form unique to each tooth crown, defining the shape of the future dentino-enamel junction.

The underlying tissue, which becomes the dental papilla, is derived from ecto-mesenchymal neural crest cells that have previously migrated into the region of the developing oral cavity. These mesenchymal tissues give rise to all of the other dental tissues: dentine, pulp, cementum and to the adjacent periodontium.

Differentiation of ameloblasts and odontoblasts, which are mesenchymally derived, results from a series of reciprocal interactions between the adjacent cells of the enamel organ and those of the dental papilla, mediated by various signalling molecules and growth factors among and between the two groups of cells.

Calcification and the formation of enamel prisms

Stimulated by the deposition of pre-dentine by adjacent odontoblasts, ameloblasts secrete an extracellular matrix of protein gel made up of amelogenins and enamelins. The local ionic environment of the extracellular fluid is supersaturated with calcium and phosphate, and the matrix proteins form an appropriate lattice for the precipitation and growth of apatite crystals.

Also sometimes called hydroxyapatite (HA), apatite is a molecule with the basic structure Ca10 (PO4)6 (OH)2 highly substituted with other ions, most notably carbonate in place of some phosphate ions, and fluoride in place of some hydroxyl ions. Strontium, sodium, zinc and magnesium may also be present in place of some calcium ions, usually in trace amounts.

Highly carbonated apatite is much more soluble than apatite with low carbonate, a significant factor in post-eruption enamel maturation as carbonate is replaced with phosphate from saliva by ion exchange. The degree of solubility of apatite also varies with the level of substitution between hydroxyl and fluoride ions. Extensive research has demonstrated that optimal levels of fluoride within apatite, most probably achieved also through ion exchange once in the oral environment rather than incorporation during initial formation, lead to the creation of enamel surfaces of very low solubility.

The apatite crystals coalesce within the gel matrix, their orientation being aligned to a strong degree, very probably because of orientation of the matrix protein molecules. The proteins dissolve as the crystals grow, creating a tissue comprised largely of apatite crystals.

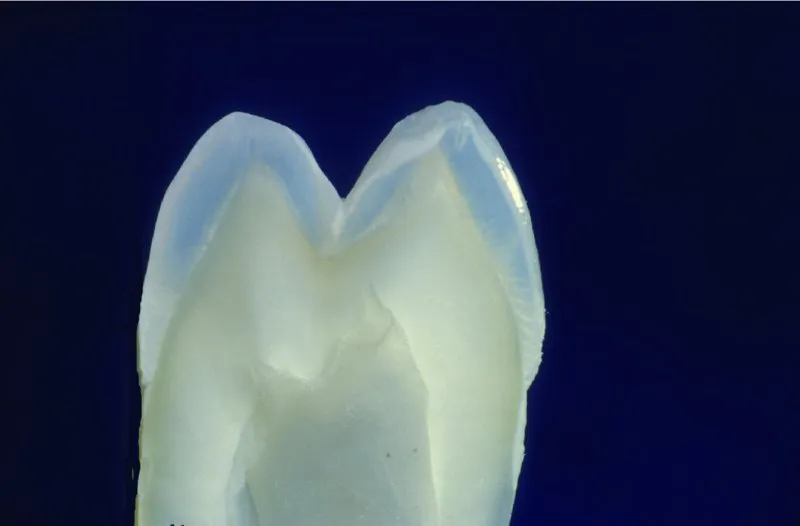

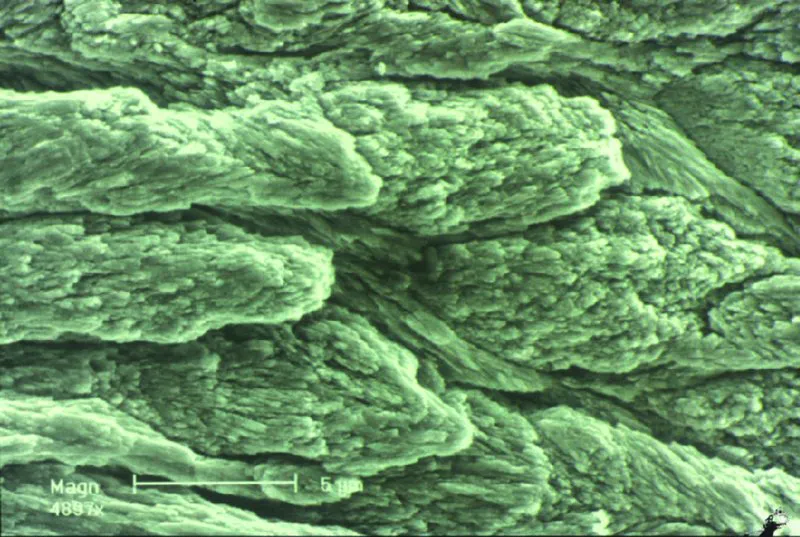

As crystal growth continues, the ameloblasts continue to secrete matrix proteins and move away from the developing hard tissue, leaving long, generally parallel apatite crystals in arrays that form enamel rods, or prisms, with a relatively enamelin-rich boundary layer between rods corresponding to the interface between individual ameloblasts in the secreting layer. There is a change in the crystal orientation near the rod boundaries, with individual rods being connected by varying amounts of inter-rod crystallites (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1 The surface of a specimen of fractured enamel showing the enamel rods, which consist of bundles of enamel crystals. The rods lie relatively parallel with each other so there is a distinct ‘grain’ along which fracture of the enamel is likely to occur. Note also the spaces between the rods that will be filled with ultrafiltrate in life. Magnification x 4,800. Courtesy of Professor Hien Ngo.

Figure 1.2 (a) Scanning electron micrograph of enamel prisms showing the int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- About the companion website

- Introduction

- 1 The Oral Environment and the Main Causes of Tooth Structure Loss

- 2 Dental Caries: Management of Early Lesions and the Disease Process

- 3 Dental Caries: Activity and Risk Assessment as a Logical and Effective Path to Both Prevention and Cure

- 4 Non-Carious Tooth Structure Loss: Diagnosis, Risk and Activity Assessment and Clinical Management

- 5 Aids to Remineralization

- 6 Systems for Classifying Defects of the Exposed Tooth Surface

- 7 Principles of Cavity Design for the Restoration of Advanced Lesions

- 8 Instruments Used in Cavity Preparation

- 9 Glass-Ionomer Materials

- 10 Resin-Based Composite Restorative Materials

- 11 Silver Amalgam

- 12 Pulpal Responses, Pulp Protection and Pulp Therapy

- 13 Choosing Between Restoration Modalities

- 14 Caries in Young Children: Special Considerations in Aetiology and Management

- 15 Oral Care of Older People

- 16 Lifestyle Factors Affecting Tooth Structure Loss

- 17 Periodontal Considerations in Tooth Restoration

- 18 Occlusion as It Relates to Restoration of Individual Teeth

- 19 Failures of Individual Restorations and Their Management

- Index

- EULA